News

6 Dec 2021 - Global infrastructure and global real estate set to shine

|

Global infrastructure and global real estate set to shine 4D Infrastructure and Quay Global Investors 17 November 2021 |

|

4D Infrastructure chief investment officer, Sarah Shaw, says inflation will be a key issue in this market but there is also great opportunity presented by the huge global infrastructure investment plans as part of stimulus programs taking place globally in the wake of COVID-19, as well as decarbonisation and its implications for infrastructure investment. "The huge global fiscal stimulus measures initiated during the COVID pandemic, combined with very accommodative Central Bank monetary policy, has led to a surge in global GDP growth. "The key risk to this story is of course inflation, and the current debate revolves around whether inflation is 'transitory' or not. However, whether inflation is transitory or more of a problem than we currently anticipate, infrastructure is still the place to be. Many infrastructure stocks have built-in inflation protection, either directly linked to tariffs or indirectly through their regulatory construct. Essentially, infrastructure, and in particular the 'user pay' sub-sector of infrastructure, is where you want to be invested in an inflationary environment. "But a far more exciting issue for us at present, as it will ultimately have a significant impact on the shape of our asset class, is that the global economy is poised to ramp up infrastructure spending. "The US Senate passed a US$1.2 trillion infrastructure plan (US$550 billion in new federal investment) that will represent the biggest burst of spending on US public works in decades. Similarly, India will launch a 100 trillion rupee (US$1.35 trillion) national infrastructure plan that will help generate jobs and expand use of cleaner fuels to achieve the country's climate goals. The EU has also announced significant infrastructure investment plans, while the May 2021 Australian Federal Budget saw the Commonwealth Treasurer identify an additional A$15.2 billion investment over 10 years on major infrastructure projects, and kept the 10-year plan at A$110 billion. "IMF research has shown this type of infrastructure spending has a real 'multiplier' effect when it comes to job creation and economic growth." Ms Shaw says the other key global area of focus is climate change and decarbonisation. "Simply put, the world cannot achieve Net Zero carbon by 2050 unless there is a huge investment in the infrastructure solution. Decarbonisation only enhances the infrastructure investment opportunity. "While the speed of ultimate decarbonisation remains unclear, there appears to be a real opportunity for multi-decade investment as every country moves towards a cleaner environment. Energy transition and decarbonisation of the power sector is an obvious thematic, and will have the greatest impact on countries looking for Net Zero. However, other forms of infrastructure, namely transportation, also have a key role to play," she says. Quay Global Investors principal and portfolio manager, Chris Bedingfield, agrees the past 18 months in markets have been challenging, but that government policy settings globally also provide some good opportunities. "While there are pockets of overvaluation in the global real estate market, there are also tremendous pockets of deep value and opportunity. "Global real estate has had a good run over the past 12 months and is up nearly 40 per cent in that time. Demand has come rushing back very quickly in terms of the stimulus that was put in consumers' hands over many months, and we've seen that in logistics, self-storage and retail - really right across the board. "In terms of where we see opportunities, one of the results of COVID-19 has been a renewed interest in some global real estate sectors that many had written off. "Take bricks and mortar retail as an example. You couldn't get investors interested in shopping centres before COVID-19. Most people were death writing the whole industry thinking that ecommerce was going to take over the whole world. "But what we've seen in the United States is a resurgence in bricks and mortar retail. The largest retail landlord in the world, Simon Property Group, just reported its third quarter sales performance - and the sales from the third quarter are higher in 2021 versus 2019 by roughly 7-8 per cent. And that is despite the fact that in the US they had rolling shutdowns. "We were starting to see the same sort of trend here in Australia with Scentre Group until the Delta strain came. So we fully expect consumers to come roaring back - not only in terms of ecommerce sales, but bricks and mortar sales as well. "We see that as an incredibly good opportunity," Mr Bedingfield says. Bennelong Funds Management CEO, Craig Bingham, adds that some of the euphoric behaviour we are seeing in global investment markets at the moment is not likely to be sustainable. "It's important to focus on investors' needs for the future. We know that history does tend to repeat itself, and it pays to bring a healthy dose of scepticism to the table when it comes to the outcome for global markets. "We've seen a lot of digital businesses evolving and coming to the fore with valuations that defy gravity. But we know we need real assets such as roads, bridges, airports, railways and real property - we can't ignore the opportunities that exist in infrastructure and real estate. "Six years ago we took the decision that our clients needed exposure to global opportunities such as listed infrastructure and listed real estate, and it was a decision that has paid off. Quay and 4D have produced some stellar numbers and have had some good results. They are showing some great momentum because they are investing today for investors' needs into the future," says Mr Bingham. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Quay Global Real Estate Fund, 4D Emerging Markets Infrastructure Fund, 4D Global Infrastructure Fund |

3 Dec 2021 - Green hydrogen is central to plans to achieve net zero

|

Green hydrogen is central to plans to achieve net zero Magellan Asset Management November 2021 The US has launched a 'hydrogen shot' known as '111' for one dollar for one kilo in one decade.[1] The UK intends to be the "Qatar of hydrogen".[2] Japan wants to be a "hydrogen society".[3] China, with 53 projects underway, is a "potential hydrogen giant" in a world where more than 350 hydrogen projects are proceeding as US$500 billion is invested by 2030.[4] Australia's government is investing A$1.2 billion to fulfil a national hydrogen strategy,[5] announcing A$275 million in its latest budget to create four 'hydrogen hubs' to generate producer economies of scale.[6] New South Wales is dangling A$3 billion in incentives to encourage A$80 billion of investment to make the state an "energy and economic superpower".[7]

Similar promises gush from Canada, the EU, France, Germany, the Netherlands and South Korea to total at least 50 worldwide,[8] while Queensland could soon be the site of the world's largest 'green' hydrogen plant. Fortescue Future Industries says it will spend A$114 million initially, and possibly more than A$1 billion in time, to build the world's largest electrolyser facility that through the process known as electrolysis would double the world's green hydrogen production capacity.[9] "Green hydrogen can save us," Fortescue proclaims.[10] Green hydrogen is certainly central in the drive to net-zero emissions because electrolysers that split water into its two elements of hydrogen and oxygen produce energy that is emissions-free; the only by-product is water vapour when it's used as a fuel. As well as being a clean fuel that burns to high temperatures, green hydrogen is an energy carrier and an input ('feedstock') for synthetic fuels. The combustible element is light and energy dense by weight (2.6 times more energy than natural gas per kilo). It can be stored and transported.[11] Hydrogen might be the most plentiful element in the solar system but it is only found in nature as a compound. That can be in gas, liquid or solid form. The element must be extracted; this is to say, manufactured. 'Green', 'renewable' or 'clean' hydrogen means the element was extracted from compounds using renewable power. The 'green' distinguishes these clean molecules from cleanish 'blue' hydrogen and dirty 'brown' hydrogen.[12] Brown hydrogen is derived when CO2-polluting fossil fuels react with steam during a simpler and cheaper extraction process called steam methane reformation. (It's called 'grey' hydrogen when natural gas, usually methane, is used.)[13] Almost all the hydrogen produced today is dirty hydrogen, which has found niche use for decades in oil refining and to produce ammonia for explosives and fertiliser.[14] Blue hydrogen is hydrogen obtained using fossil fuels, typically natural gas, where the carbon produced is captured and stored to make it a low-emissions energy source. According to the global industry body, the Hydrogen Council, announced clean hydrogen production capacity will boost clean hydrogen production to 11 million tons by 2030. If achieved, that would be an increase of 450% on 2019 levels and compares with (almost all dirty) hydrogen production today of about 70 million tons. About 70% of the flagged production by 2030 would be green hydrogen, while the other 30% would be blue. While most of the hydrogen produced today is used near where it's made, by 2030 about 30% of the hydrogen produced is expected to be transported via ships or pipelines.[15] Like fossil fuels, hydrogen (when combined with a fuel cell, the reverse process of electrolysis) can be combusted for industrial and household use and in stationary and mobile applications, including as hydrogen-power cells for electric cars, and is especially suited, advocates say, for heavier transport such as planes, rockets, ships and trucks. Hydrogen, first used to propel the earliest internal combustion engines 200 years ago is poised to help the world fight climate change for two main reasons. One is that clean hydrogen helps to overcome the biggest disadvantage of renewable energy. Solar and wind power are unreliable because they rely on intermittent sources of energy. Hydrogen can make renewable grids reliable because it is easily stored as an energy source and dispatched when needed. The other advantage of hydrogen is that it can replace fossil fuels used in manufacturing where furnaces need to reach 1,500 degrees Celsius. That hydrogen can replace the fossil fuels blamed for 20% of global carbon dioxide emissions means the element is the 'missing link' in decarbonising the 'hard-to-abate' areas of manufacturing, where electricity is not suited to generating the heat required. Such industries include agriculture, aviation, chemical manufacturing and steel making. Another benefit of hydrogen is strategic. A report in 2020 from Harvard University's Belfer Center judged the countries best placed to dominate renewable hydrogen will be those with the infrastructure in place and lots of accessible fresh water - nine litres of water is needed to produce one kilo of renewable hydrogen. It so happens that liberal democracies such as Australia, Norway and the US are hydrogen friendly. This means western powers will be less reliant on authoritarian states such as Russia and Saudi Arabia that are the world's biggest exporters of fossil fuels. "The reshuffling of power could significantly boost stability throughout global energy markets," the report says. [16] What's not to like about hydrogen? The element's big drawback is that it is more costly than dirty alternatives because it is expensive to manufacture. As a general rule, renewable hydrogen is about two to three times more costly to produce than fossil-fuel-based hydrogen.[17] In the EU context, green hydrogen costs from 2.5 to 5.5 euros a kilo versus 1.5 euros a kilo for brown hydrogen and 2 euros a kilo for blue.[18] In the Australian context, the cost of green hydrogen needs to plunge from an estimated A$8.75 a kilo now to below A$2 a kilo to be as cheap as fossil fuels. For the US to achieve its 111 shot, the cost of clean hydrogen must plummet by 80% from US$5 a kilo. Reducing the cost is the defining challenge of green hydrogen - that the cost of solar photovoltaics plunged 82% from 2010 to 2019 provides much encouragement.[19] The hydrogen industry will likewise triumph if, first, electrolysers become cheaper due to technological advances and economies of scale, second if renewable power becomes more affordable, and third if hydrogen producers can achieve economies of scale. Governments, for their part, need to offer subsidies that encourage demand and supply. Another option is they could make clean energies more price competitive by legislating a tax on carbon. While the intractable politics of climate change prevent the implementation of adequate carbon taxes, governments are providing the catalyst to engender the required economies of scale. Bloomberg New Energy Forum forecasts green hydrogen's cost could drop to US$2 a kilo by 2030 and US$1 a kilo by 2050 by when the element could supply up to 24% of the world's energy needs.[20] A world looms where clean hydrogen might play a defining role in helping the drive to net-zero emissions. The split between green and blue will depend on reducing the cost of green. To be sure, the electrolysis performed to create green hydrogen comes with the environmental challenge that it removes water supplies from where the hydrogen is produced. Doubts surrounding carbon capture and storage undermine blue hydrogen's environmental credentials. Some dismiss it as a natural-gas company marketing ploy like 'clean coal' - a recent Cornell and Stanford study says blue hydrogen is "difficult to justify on climate grounds".[21] Hydrogen, being the lightest gas in the universe, is not dense by volume. This means it must be pressurised to pipe or liquified to ship, which adds to costs. Hydrogen is volatile and can explode. The petro-states and China could prove influential enough in hydrogen and thus negate the element's strategic benefits for the west. Batteries are likely to hold their cost advantage over hydrogen fuel cells for powering electric cars. Solutions other than hydrogen (such as better battery storage, interconnected grids and smart-grid technology) could overcome the intermittent handicap of renewable power. Beware too that two decades ago, hydrogen was touted as an energy solution. George W Bush in the 2003 State of the Union, for instance, set aside US$1.2 billion so the first car driven by a child born that year would be powered by hydrogen.[22] Yet 18 years later, the green hydrogen industry still barely exists. But that's a reason for optimism. The push to derive the economies of scale needed to lower the price of hydrogen have barely started. Yet electrolyser costs have dived by around 60% over the past 10 years, and the coming economies of scale are expected to lead to a further halving by 2030, according to the financial-sector-backed Sustainable Markets Initiative, which expects green hydrogen to be price competitive against fossil-fuel-based hydrogen by 2030.[23] If so, the countries hyping the element are likely to fulfil their hopes for an element that today shapes as a key technological pathway to net-zero emissions. Political shortfall President Joe Biden, to emphasise the priority he placed on climate change, announced the US would rejoin the Paris Agreement on his first day in office.[24] One week later on January 27, Biden took "aggressive" executive actions "to tackle the climate crisis" that included a writ that climate considerations be an "essential element" of US foreign policy.[25] In April, Biden committed the US to slashing emissions by 50% by 2030 from 2005 levels because climate change posed an "existential threat".[26] Yet in August, the White House demanded Opec boost oil production because high petrol prices "risk harming the ongoing global recovery".[27] While on his way from Italy to the UN climate change conference of world leaders in the UK in October, Biden admitted the situation "seems like an irony".[28] Rather than ironic, Biden's actions are incompatible. But that's understandable, especially for a president whose climate-change steps have been hobbled by a Congress under his party's control. The political resistance against tackling climate action has proved intractable for decades for three broad reasons. The central political problem is that steps to lower emissions impose immediate costs and there are limits to what people will stomach. Economists (among others) argue the best way to reduce carbon emissions is to tax carbon. The IMF says carbon taxes need to rise from its estimate of US$3 a ton now to US$75 a ton by 2030 to reduce emissions as targeted.[29] But taxes are unpopular, especially among the working class, as the 'gilets jaunes' protests over higher oil and fuel prices in France from 2018 to 2020 showed. Carbon taxes are regressive because the poorer spend a greater proportion of their incomes on energy. The taxes cost jobs in targeted industries. They hurt the countries and communities dependent on these energies. They promote a general rise in prices that has flow-on effects for interest rates. A World Bank tracker highlights the world's failure to impose taxes on carbon. The gauge shows that installed or coming carbon taxes cover only 21.5% of global emissions.[30] These taxes are generally set too low to make much difference anyway. Some say the effective price of carbon emissions across the world is essentially zero.[31] As there's little sign that will change, policymakers must resort to regulatory actions, subsidies and possibly carbon tariffs on imports to change behaviours - and they come with political blowback too. The second challenge is the 'free rider' problem. If most countries take action to reduce emissions, there is less incentive for the reluctant to do so. (The other way to view this difficulty is as the first-mover disadvantage.) The third is the sequencing problem. Emerging countries protest they are being asked to forgo prosperity to mitigate the damage caused when advanced countries became rich on cheap fossil fuels. Emerging leaders sabotaged the UN climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009 for this reason.[32] The thorny politics explain why policymakers invest so much hope in technology. This is the context in which to view the promise of hydrogen. Bloomberg New Energy Group says seven indicators will determine whether or not a hydrogen economy emerges. The first is that countries legislate net-zero climate targets to force hard-to-abate industries to decarbonise. The second is that standards governing hydrogen use are harmonised and regulatory barriers removed, to reduce obstacles for hydrogen projects. Three, targets with investment mechanisms are needed to provide a motive for investment. Four, harsh heavy transport emission standards must to be set to promote a shift towards hydrogen as a fuel. Five, mandates and markets for low-emission products be formed. Six, industrial decarbonisation policies and incentives are established. Last, hydrogen-ready equipment becomes commonplace, which enables and reduces the cost of switching to hydrogen.[33] Meeting 24% of energy demand with hydrogen in a 1.5 degree Celsius scenario will require huge amounts of additional renewable electricity generation. In this scenario, about 31,320 terawatts of electricity would be needed to power electrolysers - more than is produced worldwide nowadays from all sources, the group says. Add to this the projected needs of the power sector - where renewables are also likely to expand massively if deep emission targets are to be met - and total renewable energy generation excluding hydro would need to top 60,000 terawatts compared with less than 3,000 terawatts in 2020.[34] Even amid such production challenges, hydrogen's biggest barrier is price. Some of hydrogen's biggest supporters admit to doubts about overcoming hydrogen's cost disadvantage. Former Australian chief scientist Alan Finkel, who forecasts Australia will be the world's biggest hydrogen exporter, says "in practice the future costs of both green and blue hydrogen remain unknown".[35] There are, however, plenty of optimists. A study by INET Oxford released in September found most energy-economy models underestimate deployment rates for renewable energy technologies and overegg their costs. The study suggests that if batteries, solar, wind and hydrogen electrolysers match recent exponential growth for another decade, the world will attain a "near-net-zero emissions energy system within 25 years".[36] Marco Alverà, the CEO of Italy's energy-infrastructure giant Snam and the author of The Hydrogen Revolution, is another optimist. Green hydrogen priced at US$5 a kilo or US$125 a megawatt-hour compares with about US$40 a megawatt-hour for oil and about US$60 a megawatt-hour for natural gas in Europe, he notes. "What's needed to get us from the current US$5 a kilo to US$2 or even US$1? The answer is that we need to make more of it," Alverà says. "The potential economies of scale are staggering: just 25 gigawatts of electrolyser production capacity - globally - could bring the cost of hydrogen to US$2 a kilo when combined with cheap renewable power."[37] Another cause for optimism is that nuclear energy, a reliable emissions-free source of power, is suited to power the electrolysis process that makes green hydrogen. The nuclear industry in the UK reckons it can produce 33% of the country's clean hydrogen needs by 2050.[38] Oil and gas companies moving away from fossil fuels are another possible driver of the hydrogen economy. The US's 111 strategy will no doubt be successful if it is read as one dollar one kilo one day. And there's a good chance the day when such technological advances overcome the political failures to mitigate climate change will be soon enough. Written By Michael Collins, Investment Specialist |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund [1] US Department of Energy. Hydrogen. energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot [2] UK government. 'PM speech at the Global Investment Summit: 19 October 2021.' gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-at-the-global-investment-summit-19-october-2021 [3] Japanese government. 'Creating a hydrogen society to protect the global environment.' 2017. japan.go.jp/tomodachi/2017/spring-summer2017/creating_a_hydrogen_society.html [4] Hydrogen Council and McKinsey & Company. 'Hydrogen insights. An updated perspective on hydrogen investment, market development and momentum in China.' July 2021. Page 3. hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Hydrogen-Insights-July-2021-Executive-summary.pdf [5] Australian government. 'Growing Australia's hydrogen industry.' Undated. industry.gov.au/policies-and-initiatives/growing-australias-hydrogen-industry [6] Speech by Angus Taylor, minister for industry, energy and emissions reduction. 'Keynote address at the 2021 Australian hydrogen conference.' 26 May 2021. minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/taylor/speeches/keynote-address-2021-australian-hydrogen-conference [7] NSW government. 'NSW hydrogen strategy to drive investment, create jobs and power prosperity.' 13 October 2021. nsw.gov.au/media-releases/nsw-hydrogen-strategy-to-drive-investment-create-jobs-and-power-prosperity [8] International Energy Agency. 'The future of hydrogen.' June 2019. [9] 'Regional workers the winners as Fortescue Future Industries announced Global Green Energy Manufacturing Centre for Queensland.' 10 October 2021. com.au/news/regional-workers-the-winners-as-fortescue-future-industries-announces-global-green-energy-manufacturing-centre-in-queensland/ [10] ffi.com.au/. As at 28 October 2021 [11] Technically, hydrogen purrs. The electrochemical reaction between hydrogen in fuel cells and oxygen drawn from the air generates electricity more efficiently than does conventional thermal generation (where the chemical energy of fuels becomes thermal energy that turns turbines to create electricity). [12] 'Pink' hydrogen is hydrogen made from nuclear, 'turquoise' if it is made using electricity to heat methane whereas blue and grey hydrogen are made from methane via the combustion of fossil fuels. [13] Dirty hydrogen is often called 'black' hydrogen when it's derived from coal. [14] NSW government. 'NSW hydrogen strategy.' October 2021. Page 15. Ammonia is made by combining hydrogen with nitrogen. nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/GOVP1334_DPIE_NSW_Hydrogen_strategy_FA3%5B2%5D_0.pdf [15] Hydrogen Council et al. Op cit. Page 4. Total world production figure from the International Energy Association op cit. [16] Fridolin Pflugmann and Nicola De Blasio. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. 'Geopolitical and market implications of renewable hydrogen.' March 2021. Page 35. belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/Geopolitical%20and%20Market%20Implications%20of%20Renewable%20Hydrogen.pdf [17] Pflugmann and De Blasio. Op cit. Page 10 [18] Sustainable Markets Initiative. 'Energy Transition. Briefing Note.' Page 9. a.storyblok.com/f/109506/x/043fbf2a45/lseg-smi-energy-transition.pdf [19] International Renewable Energy Agency. 'How falling costs make renewables a cost-effective investment.' 2 June 2020. irena.org/newsroom/articles/2020/Jun/How-Falling-Costs-Make-Renewables-a-Cost-effective-Investment [20] Bloomberg New Energy Forum. 'Hydrogen economy outlook.' 30 March 2020. For forecast price drop, see figure 3 on page 3. For world energy needs forecast, see page 8. data.bloomberglp.com/professional/sites/24/BNEF-Hydrogen-Economy-Outlook-Key-Messages-30-Mar-2020.pdf [21] Robert Howarth and Mark Jacobson. 'How green is blue hydrogen?' Energy Science & Engineering. 12 August 2021. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ese3.956. See also 'Fossil fuel companies say hydrogen made from natural gas is a climate solution. But the tech may not be very green.' TIME. 22 September 2021. time.com/6098910/blue-hydrogen-emissions/ [22] George W. Bush. 'Transcript of State of the Union.' 2003. cnn.com/2003/ALLPOLITICS/01/28/sotu.transcript.5/index.html [23] Sustainable Markets Initiative. Op cit. Page 9. [24] The White House. 'Paris climate agreement.' 20 January 2021. whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/paris-climate-agreement/ [25] The White House. 'Fact sheet: President Biden takes executive actions to tackle the climate crisis at home and abroad, create jobs, and restore scientific integrity across federal government.' 27 January 2021. whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/27/fact-sheet-president-biden-takes-executive-actions-to-tackle-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad-create-jobs-and-restore-scientific-integrity-across-federal-government/ [26] The White House. 'Fact sheet: President Biden sets 2030 greenhouse gas pollution reduction target aimed at creating good-paying union jobs and securing US leadership on clean energy technologies.' 22 April 2021. whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/22/fact-sheet-president-biden-sets-2030-greenhouse-gas-pollution-reduction-target-aimed-at-creating-good-paying-union-jobs-and-securing-u-s-leadership-on-clean-energy-technologies/ [27] The White House. 'Statement by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on the need for reliable and stable global energy markets.' 11 August 2021. whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/11/statement-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-the-need-for-reliable-and-stable-global-energy-markets/ [28] The White House. 'Remarks by President Biden in press conference.' 31 October 2021. Rome, Italy. whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/10/31/remarks-by-president-biden-at-press-conference-in-rome-italy/ [29] IMFBlog. 'A proposal to scale up global carbon pricing.' 18 June 2021. blogs.imf.org/2021/06/18/a-proposal-to-scale-up-global-carbon-pricing/ [30] The World Bank. 'Global carbon dashboard.' carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/ [31] Foreign Affairs. 'Why climate policy has failed.' 12 October 2021. foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-10-12/why-climate-policy-has-failed [32] Andrew Charlton, economic adviser to Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd. 'I hate to say it, but Barnaby has a point on climate.' 29 October 2021. smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/i-hate-to-say-it-but-barnaby-has-a-point-on-climate-20211028-p593uu.html. A fourth challenge might be the 'not in my backyard' syndrome that hobbles the building of renewable energy plants including nuclear ones due to their visual pollution, damage to the natural environment and perceived risks. [33] Bloomberg New Energy Forum. Op cit. Page 10 [34] Bloomberg New Energy Forum. Op cit. Pages 8 and 9 [35] Alan Finkel. Australia's chief scientist from 2016 to 2020 and special adviser to the Australian government on low-emissions technology. 'Green or blue, our future with hydrogen is bright.' The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 October 2021. smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/blue-or-green-our-future-with-hydrogen-is-bright-20211014-p58zug.html [36] Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) at the Oxford Martin School. Rupert Way et al. 'Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition.' 14 September 2021. inet.ox.ac.uk/files/energy_transition_paper-INET-working-paper.pdf [37] Marco Alverà, the CEO of Italy's grid operator Snam. 'The main obstacle to hydrogen becoming the green fuel of the future is cost - but maybe not for long.' 19 September 2021. The Independent. independent.co.uk/climate-change/opinion/hydrogen-green-fossil-fuels-electricity-b1921520.html [38] Nuclear Industry Association. Media release. 'Government and industry back nuclear for green hydrogen future.' 18 February 2021. niauk.org/media-centre/press-releases/government-industry-back-nuclear-green-hydrogen-future/ Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 ('Magellan') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should read and consider any relevant offer documentation applicable to any investment product or service and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making any investment decision. A copy of the relevant PDS relating to a Magellan financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any strategy, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to be implemented and its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any trademarks, logos, and service marks contained herein may be the registered and unregistered trademarks of their respective owners. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan. |

2 Dec 2021 - Managers Insights | Equitable Investors

|

|

||

|

Chris Gosselin, CEO of FundMonitors.com, speaks with Martin Pretty, Director at Equitable Investors. The Equitable Investors Dragonfly Fund has been operating since September 2017. Over the past 12 months, the fund has returned +45.96%, outperforming the index by +18%, which returned +27.96%.

|

2 Dec 2021 - You've got to know when to hold 'em, Know when to fold 'em

|

You've got to know when to hold 'em, Know when to fold 'em Ophir Asset Management November 2021 |

|

Insight into Ophir's portfolio turnover You've no doubt heard these classic lyrics from one of Kenny Rogers' hit songs at some point in your life. For one of your writers, their first memory comes from hearing it repeatedly at a local Uni bar as one of the last songs of the night back in the 90s. This usually meant it was time to go home!

Of course, Rogers was singing about a game of cards, but the words could equally apply to managing a share portfolio. Imagine a share you own has just gone up 20% on the day of its latest earnings announcement because it 'beat' earnings expectations and it raised its profit outlook. Should you continue to 'hold 'em'? Or what if one of your key portfolio positions has just tanked 30% after a poor earnings update at its latest AGM. Should you 'fold 'em'? Or perhaps should you even run?! Many investors who put some of their life savings with a fund manager want to know what the manager's 'portfolio turnover' might be. That is, does the manager hold positions in companies for a very long time, happy to look through any short-term bumps in the road, resulting in low turnover? Or are they more active, trying to make every post a winner, changing weights of stocks in the fund frequently, or perhaps selling out entirely and introducing new companies at a more rapid pace - racking up higher turnover? Who cares about portfolio turnover? Well, trading costs money. You don't see it turn up in the management expense ratio, which is what the fund manager charges you. But it does come out of the investors' assets - going to brokers for buying and selling companies. For professional investors, this can often cost anywhere from 0.1-0.3% of the value of the stock traded. Source: New Yorker There is a well-known and very funny book called 'Where are the Customers' Yachts?' on this very topic. It's about a visitor to New York who admired the boats of the wealthy stockbrokers, but couldn't understand why their clients didn't have their own luxurious boats. Author, Fred Schwed Jr, starts the book with:

It's sometimes argued fund managers don't have an incentive to keep transaction costs from portfolio turnover low as they are not the ones that directly bear the cost. This may be true to a degree, but not at Ophir. Remember, we have all our investable wealth in the Ophir funds, so we care greatly about transaction costs from buying and selling and the resultant portfolio turnover. We'll only trade if we have high conviction that it will add value, AFTER costs. How you can have 100% turnover but still own the same stocks as a year ago Portfolio turnover happens any time a stock is bought or sold, either partially or in full. The generally accepted formula for how a fund manager's portfolio turnover is calculated is below. So, if you bought $12 million of stocks and sold $10 million during the year, whilst the average fund value was $10 million, then your turnover would be 100%. Some say this is the same as having a whole new line-up of stocks in the portfolio on the 31st of December, compared to a year ago on the 1st of January. But this is not strictly true. As well as FULL buy and sells (that introduce new and remove old stocks from the portfolio), the buys and sells include PARTIAL buy and sells (otherwise known as re-weighting of positions). So technically it's possible to still hold the exact same stocks at year-end as the beginning, and still have 100% portfolio turnover, from very active reweighting of positions (though this would be incredibly rare!). For equity funds, low turnover is generally regarded as less than 20-30% p.a. Whereas high turnover is often thought of as above 80% p.a. Is high turnover bad? If you're cost-conscious, you might immediately think that a high portfolio turnover is bad because more transaction costs are subtracted from your assets - only enriching the brokers and funding their next luxury yacht. But that is not the full story. If the transactions add more value than their cost, then they should be executed. Academics haven't helped us much. The evidence from their research is mixed as to whether high portfolio turnover adds or subtracts from net investment performance on average. Digging a little deeper, though, and what you generally find is that the best performing high-turnover equity funds outperform the best-performing low turnover funds, but the worst also do worse. So, get it right and the potential gains may be higher, but get it wrong and the downside is also greater. You also find that, on average, high turnover funds don't last as long. But this is just the poor-performing high-turnover funds going out of business because they underperform the worst-performing low-turnover funds. Would Kenny go disco? Your fund type and turnover For investors, one way to check if a manager is behaving "true to label" is whether their portfolio turnover is in line with their investing style. Just as you expect Kenny Rogers to keep churning out country hits, you might get a little worried if he tried to reinvent himself with a new dance floor anthem! On the low turnover end are passive index tracking funds. Here for example, Vanguard's S&P500 tracking funds typically have turnover as low as 3-4% p.a. as they are basically just buying and holding the index constituents and only changing them when the index (infrequently) changes. If you find out your passive index tracking fund has turnover of greater than 30% p.a. - that's a massive red flag! Amongst active managers, next up is usually "Value" style managers with a long-term investment horizon that seek to buy more mature undervalued businesses and wait for the market to realise they were previously selling cheaper than they should have. More "Growth" orientated managers usually have a higher turnover as they seek out more rapidly growing businesses that are more likely to be sold once growth slows or is replaced by the next high growth company. Overall, active style equity funds on average typically have turnover around 60-100% p.a. but with a wide variety to be found outside these ranges. For example, for some hedge funds or highly active high octane quantitative style equity managers, turnover over 500% p.a. can often be found! Revealing our hand. What's our turnover at Ophir? So that brings us to what you're all here for. Where do Ophir's funds sit on the turnover spectrum and what does it say about how we are managing your money? The best gauge of the turnover at Ophir is our longest-running fund, the Ophir Opportunities Fund, which has been going for a little over nine years. Its turnover is close to 100% p.a. on average, over the long term, which on face value is high compared to many other active equity managers. About 40% of this turnover though has been from FULL buys or sells - that is, new stocks entering the portfolio or old stocks being sold in full. The other 60% results from partial buys and sells, or in other words, reweight existing positions based on our analysis and changes in our conviction levels. The 40% of turnover resulting from full buys or sells means that the average holding period of a stock in our original Ophir Opportunities Fund is about 2.5 years. Now that's an average. Sometimes we hold positions in companies for as little as a few months, but sometimes for longer than 5+ years. It is not something that is predetermined. Ultimately, turnover is an output of our investment process and it depends on how long it takes, if at all, for the market to realise the value we see in the companies we hold. If we discover an undervalued business that is growing quickly, and the market fully realises that value at its next earnings result in a few months' time, then we may recycle that capital into the next idea that has bigger upside. Alternatively, if the market only partially realises the value, then we may continue to hold if we see further big gains ahead. Again, turnover is an output, not something we target ahead of time. So, in sum, we are quite active, and more active than most. We would be worried if turnover went down significantly because it would probably mean that we weren't finding as many new ideas to keep the expected return of our funds high. But remember, much of our activity is also making sure we have the position sizing right for the conviction levels we have in our holdings. As George Soros once said:

In funds management, position sizing is not everything, but it is almost. Do our different Ophir funds have different turnover? In short yes. Ranking our Ophir funds from highest turnover to lowest over time goes something like this: Global Opportunities Fund > Ophir Opportunities Fund > Ophir High Conviction Fund.

What causes our turnover to change Whilst 100% p.a., on average, is a good yardstick to keep in mind for turnover of the Ophir funds over the long term, it can and does change significantly from year to year. What causes it to change? Many things, but mostly the number of new ideas we have for the funds at any one point in time and the performance of existing positions. Turnover highly correlates with performance. When performance is high, turnover tends to be high. And causation runs both ways here. That is, if we have a high number of new ideas, then we are frequently selling existing positions to fund those ideas with higher expected returns. At the same time, if those higher returns bear out, then we are more likely to either sell some of them for risk management purposes, so they don't represent too much of the portfolio, or they have met their price target and we are recycling the capital into new ideas to keep the expected return of the fund high. Turnover also tends to increase during significant market events. A classic recent example is March last year when COVID-19 first hit. We reshaped our portfolios to take account of the new reality that faced economies, companies and markets, using the price volatility in shares to buy those that were oversold as fear gripped markets. Likewise, when effective vaccines news hit the airwaves in November last year, it required meaningful portfolio readjustments as the starter's gun was fired on an eventual return to some form of normality. An example of higher turnover has been the Global Opportunities Fund in recent years, where its very high performance and COVID-19 related re-shuffling saw turnover significantly higher than 100% pa at different times. We think its turnover is likely to trend down as hopefully no more COVID-like events are around the corner anytime soon (!) and abnormally high performance moderates somewhat (though we'd be quite ok if it doesn't!). When we fold. The four factors that trigger us to sell a stock When talking about portfolio turnover we must also mention the four main triggers that cause us to sell a stock. 1. Earnings snag The first, and certainly the most worrying trigger, is when the earnings trajectory of the company seems to have hit a snag and no longer has us as excited. It's worrying because this is what we hang our hat on when doing our due diligence on businesses, i.e., we are highly confident they are growing faster than the market thinks. We are going to get some companies wrong though, that is life, business is risky. Things come out of the blue and even smack the (hopefully) most informed person on the business, the CEO, in the face. But we need to make sure that when these shocks happen that they are infrequent, small and we limit their impact by having a lower portfolio weight. 2. Overvalued The second reason we sell is when a stock just becomes too expensive. Not every company, no matter how wonderful or how quickly it is growing, makes a great investment. It can be too expensive. Or in other words, it can be factoring in too rosy a future. Plus, if you are wrong on the earnings trajectory, as above, at least you won't be compounding it too much if you are continually trimming the expensive flowers. 3. Thesis change The third, and probably our biggest pet peeve of the bunch, is when the investment thesis changes for a stock. That is, we were holding it for one reason, but that reason no longer exists and we, or another analyst in the team, have found another reason to keep holding the position. This is an automatic sell for us. If we've lost our edge on the original reason the company was a 'buy' for us, then we shouldn't be hanging around for another reason just to justify inaction. 4. Something better And lastly, but probably the most frequent reason for selling, is simply we have found something better. If a new company is growing more quickly, trading at a cheaper valuation than one of the lowest conviction positions in the fund, then there is a good chance it will be out with the old and in with the new. Fresh ideas are the lifeblood of funds management and help ensure that new investors to the Ophir funds stand a chance of receiving returns as good if not better than those who have been with us for years. Why we won't cut turnover to minimise tax One of the side effects of portfolio turnover is its impact on distributions from managed funds, including our own. The higher your turnover, the more likely you are to generate realised gains or losses. And if you are getting it right, your gains will handsomely outstrip your losses over time. Typically, equity managed funds must distribute realised capital gains every year to investors for tax purposes. All else equal then, a higher turnover fund will have to distribute more of its return to investors. We sometimes have investors who are disappointed to receive a significant annual distribution from our funds comprised of realised gains - given many must pay tax on those gains, depending on their investment entity. Whilst we very much understand where these investors are coming from (no one likes to pay more tax than they need to, including ourselves) we are reminded that a wise man once said:

If we didn't sell when we thought it appropriate, just to avoid generating these realised gains, we'd ultimately provide lower total returns in our funds and incur more risk. Or in other words, we'd be cutting off our nose to spite our face. We never want to have the 'tax tail' wag the 'investment dog'. We can assure you both of us face a stiff marginal tax rate on our holdings in the Ophir funds. We also naturally have many investors in our funds with all manner of different marginal tax rates they face depending on which vehicle they invest through, from 0%, all the way up to the top marginal tax rate. The one thing we can assure you is that we and the team are working our hardest every day to ensure we are providing the best investment return to you without taking undue risk. We will remain quite active in our approach, as it has served us well in the past, and strongly believe it will continue to in the future. Written By Andrew Mitchell & Steven Ng, Co-Founders & Senior Portfolio Managers |

|

Funds operated by this manager: |

|

This document is issued by Ophir Asset Management Pty Ltd (ABN 88 156 146 717, AFSL 420 082) (Ophir) in relation to the Ophir Opportunities Fund, the Ophir High Conviction Fund and the Ophir Global Opportunities Fund (the Funds). Ophir is the trustee and investment manager for the Ophir Opportunities Fund. The Trust Company (RE Services) Limited ABN 45 003 278 831 AFSL 235150 (Perpetual) is the responsible entity of, and Ophir is the investment manager for, the Ophir Global Opportunities Fund and the Ophir High Conviction Fund. Ophir is authorised to provide financial services to wholesale clients only (as defined under s761G or s761GA of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)). This information is intended only for wholesale clients and must not be forwarded or otherwise made available to anyone who is not a wholesale client. Only investors who are wholesale clients may invest in the Ophir Opportunities Fund. The information provided in this document is general information only and does not constitute investment or other advice. The information is not intended to provide financial product advice to any person. No aspect of this information takes into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of any person. Before making an investment decision, you should read the offer document and (if appropriate) seek professional advice to determine whether the investment is suitable for you. The content of this document does not constitute an offer or solicitation to subscribe for units in the Funds. Ophir makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information it provides, or that it should be relied upon and to the maximum extent permitted by law, neither Ophir nor its directors, employees or agents accept any liability for any inaccurate, incomplete or omitted information of any kind or any losses caused by using this information. This information is current as at the date specified and is subject to change. An investment may achieve a lower than expected return and investors risk losing some or all of their principal investment. Ophir does not guarantee repayment of capital or any particular rate of return from the Funds. Past performance is no indication of future performance. Any investment decision in connection with the Funds should only be made based on the information contained in the relevant Information Memorandum or Product Disclosure Statement. |

1 Dec 2021 - Fixed Income Dilemma

|

Fixed Income Dilemma Laureola Advisors 14 November 2021 The global financial crisis, COVID and bank deposit rates that are often negative in some countries means that the need for diversification of retirement earnings is not a textbook concept. As part of the process of formulating and regularly reviewing the Self-Managed Super Fund (SMSF) investment strategy, there is a requirement to consider diversification. Diversify how? Share market is booming but most portfolios can't take anymore equities' risk. SMSFs need to spread their capital across a range of investment types to reduce the risk of being exposed to one or a small number of poorly performing investments. SMSFs looking for assets that are uncorrelated with equity markets could consider investments such as life settlement funds, which invest in United States life insurance policies. Bonds offer no respite from low returns Bonds no longer offer the traditional and desired characteristics of diversification, cash income to beat inflation and providing investors with "Sleep at Night" comfort levels. Fixed income offers fundamental investors no respite. Government bonds yield near zero, despite the Fed abandoning its inflation targets in favour of job growth. Speculative High Yield bonds offer 5.6%, but with rapidly deteriorating credit risk. The worst news for bond investors may come from Credit Suisse, whose analysis confirms that, in today's markets, bonds no longer offer diversification from equity risk. Many investors have turned to real estate or real estate debt for fixed income alternatives but there are danger signs here too. One asset class still providing an attractive risk/return profile is Life Settlements, which continues to offer strong fundamentals, an above average yield, low credit risk, and genuine diversification. Written By Tony Bremness Funds operated by this manager: |

1 Dec 2021 - 4D podcast - the role of infrastructure in reaching net zero

|

4D podcast - the role of infrastructure in reaching net zero 4D Infrastructure 01 November 2021 With the COP26 summit upon us, Sarah Shaw weighs in on decarbonisation. "Decarbonisation must happen, and the goal of net zero is just not achievable without the right form of infrastructure investment." With COP26 dominating conversation in Australia, 4D's Sarah Shaw speaks with Bennelong's Holly Old about the role infrastructure will play in the decarbonisation opportunity, particularly within high carbon-emitting industries such as energy and transport. Speaker: Sarah Shaw, 4D Infrastructure Chief Investment Officer (CIO) Time Stamps: |

|

Funds operated by this manager: 4D Global Infrastructure Fund, 4D Emerging Markets Infrastructure Fund |

1 Dec 2021 - What to do with Miserly Cash and Bonds

|

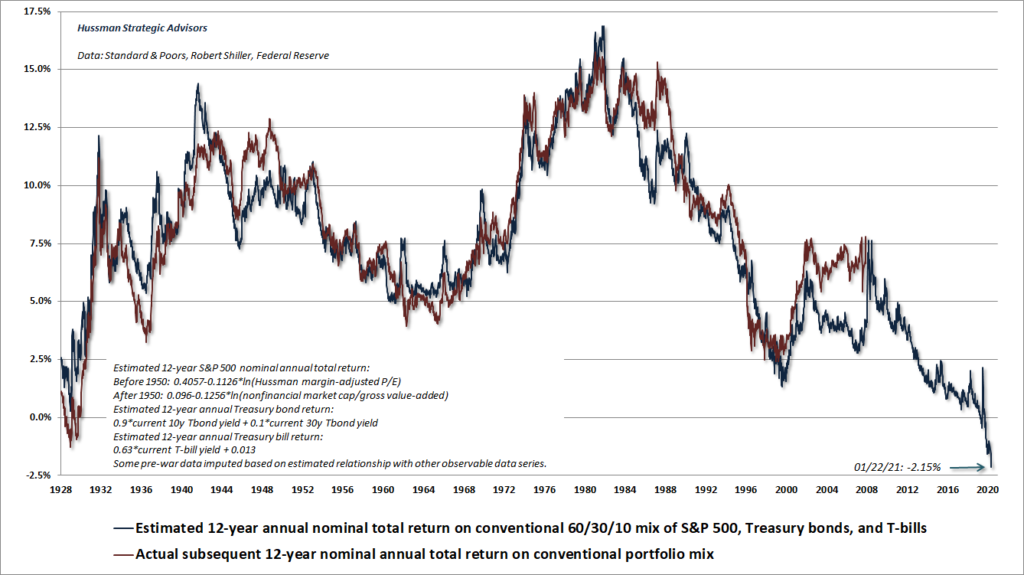

What to do with Miserly Cash and Bonds Wealthlander Active Investment Specialist 24 November 2021 Introduction Investors naturally fleeing cash and bonds in response to inadequate yields, poor prospective returns, and government monetary and fiscal policies. The narrative of "There Is No Alternative" (TINA) is rampant as investors look to equities as the go-to asset class for a significant proportion of their capital. Unfortunately, this appears imprudent and could even potentially prove entirely mistaken. In this article, we will explore the critical mistake investors are making in thinking "There is No Alternative" when considering their asset allocation and reveal a real emerging alternative to low cash and bond rates. We will explore how this alternative is essential to a good investment and incredibly prospective in terms of meeting prudent absolute return investor objectives and provides a less risky option to being all-in on risk assets. Why Cash and Bonds are on the Nose? Many investors and institutions allocate their assets among some combination of the following asset classes: cash, bonds, property, and equities, in line with their perceived risk profile and investment mandates. Cash and bonds are the traditional defensive assets while property and equities are the traditional risk-on or growth assets. The traditional 60:40 portfolio, or a variation thereof, is used as a kind of passive and lazy basis for portfolios for institutional investment management for the last 40 years. It includes 60% equities and property and 40% cash and bonds. It has been effective historically at producing modest risk-adjusted returns as it has benefited across the board from disinflation and lower interest rates, which has been a structural trend since the early 1980s. However, now that cash rates have gone all the way to 0 (0.1% in Australia) and bonds have a circa 1% yield, history will not be able to repeat itself in coming years. Furthermore, it is realistic that we may even see the reverse happening as inflation and interest rates begin to rise. Hence, in contrast to seeing the lovely tailwind for all traditional asset portfolios, we may very realistically see a significant and adverse macroeconomic headwind in the coming years. Furthermore, these asset classes are not priced for this to occur as they - and consensus - are dominated by passive investors who are largely trend following in nature, and who buy irrespective of value. It shows by the exponential growth of passive ETFs that predominantly track a market benchmark. If the massive structural trend changes, traditional assets, and portfolios can be expected to lose from the change in a big way. Most notably, higher inflation is terrible for most non-inflation indexed bonds (and long-duration assets). Higher discount rates would also challenge highly elevated property and equity valuations that are dependent on low discount rates. Some of these growth assets are arguably deeply divorced from fundamentals because of the TINA mantra and a broad consensus belief that central banks can be relied upon to keep interest rates low forever. Interestingly, there are credible forecasts such as Hussman (see chart below), that equities may not provide the high returns investors are generally expecting. Cash and bonds - even with low-interest rates - are priced to provide inadequate returns to meet even modest return expectations. Investors are hence needing alternative investments with greater return prospects and different rather than common, drivers of return and risk. Predicted and Actual Returns on Conventional 60/30/10 Portfolios

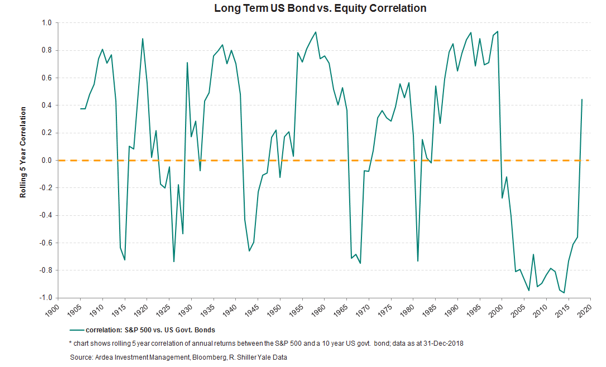

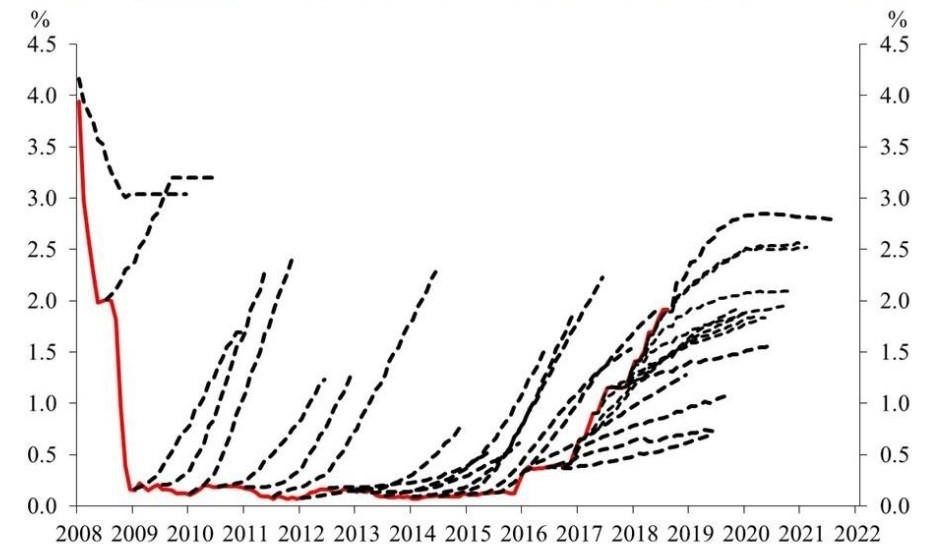

Source: Hussman Funds Bonds have often been included in a portfolio for their diversification benefits, on the view that they will perform well when equities underperform and hence lower the huge risk from being only inequities. However, this relies heavily upon bonds having a negative correlation with equities. Unfortunately, history tells us even this cannot be relied upon - and given starting yields and key portfolio risks such as inflation and higher yields today - we should not rely upon bonds being diversifying, as they may not be. There are many times in history when bonds simply do not diversify equity risk, most particularly when inflation rises, and long-term interest rate expectations rise too fast or above critical levels. Given current government policy around the world is to print and spend with abandon until we get inflation or some other calamity, inflation as a risk should clearly not be ruled out. Disinflation should simply no longer be relied upon as the basis to build an entire portfolio, which as an aside basically completely invalidates most passive portfolio approaches. Paradoxically, these portfolios or index-focused investment styles are more popular than ever. Furthermore, we know from watching central banks for a very long time that their prognostications about future interest rates and inflation have routinely been incorrect. In contrast, they can be somewhat relied upon to follow the market when market conditions push them to do so. They are also influenced by banks and other market participants pushing them around publicly and otherwise when it suits them - indeed we know of at least one activist fund manager that does this to the RBA (and presumably he does so because he thinks it is effective). One of the greatest fallacies we commonly hear is that central banks control our economies and determine growth and inflation and other economic settings. Simply, we don't believe there is any compelling evidence to suggest they control these. Hence, don't assume they do.

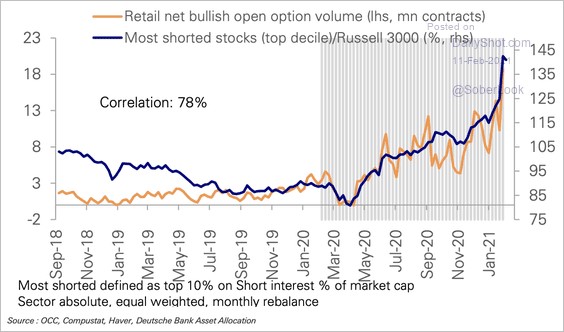

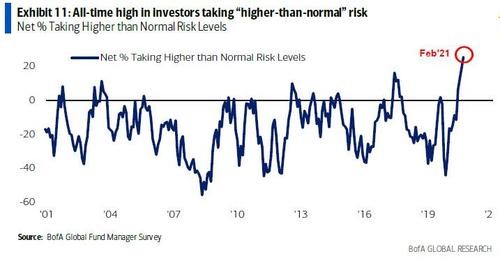

Source: FRB, Bloomberg Finance LP, DB Global Research. Note: Data for the graph courtesy of Torsten Slok, Deutsche Bank Whether you stick with the traditional portfolio or move more into equities, if you are constrained to traditional long-only assets, you will probably end up with a much riskier and lower returning portfolio today than you had before. Bonds may no longer protect and diversify, and equity risk is escalating with the nature of the investors in equities and higher valuations bringing down future return forecasts. There is certainly plenty to be concerned about contrary to consensus (and I haven't even mentioned Taiwan). Expect a Paradigm Shift We can see rampant signs of speculation on equities, and the period we're living through is very reminiscent of late 1999. For instance, there is massive call volume bidding up the prices of the worst quality and most shorted stocks in the market (see diagram below), as well as less shorting in markets than we've seen for a very long time. We could potentially see continuing rises on equities driven by price-insensitive buyers such as index investors and speculators, before a massive market collapse similar to 1987 or early 2000 when the trend reverses. This is what happens in bubbles - they become removed from fundamentals, escalate, last longer than anyone expects, and then - often with unpredictable timing - they collapse. Bidding up the Prices of the Worst Quality and Most Shorted Stocks in the Market Source: OCC, Compustat, Haver, Deutsche Bank Asst Allocation Note: Most shorted defined as top 10% on short interest % of market cap. Sector absolute, equal weighted, monthly rebalance. We have not had high and increasing inflation for decades. It should be clear that while "this time may not be different", it is very different from the time period which most investors, advisers and institutions have worked through. Importantly, some advisers and institutions are inflexible and hopelessly ill-equipped to manage well anything other than a rising market. The real question is not what short-term return will be achieved while the bubble inflates, but whether your assets are being risk-managed and what your compounded return is over time when markets turn south. Given many investors are doing exactly what they did in early 2020 when we last witnessed great market complacency, it may be instructive to see what happened to your portfolios in early 2020; how badly was your approach hurt from a market crisis, and how quickly did your approach recover from these falls (if at all?). Prima facie, while it may be very exciting, far from increasing equities and risk assets into escalating prices and speculative mania, it could very reasonably be argued that it is more reasonable for a prudent investor to be reducing risk when risk-loving is rampant or at least not increasing their exposure. This is even more important for conservative investors or for those who can't tolerate huge losses. It is very difficult to tell when the music will stop, so playing musical chairs with dangerous markets will not suit more conservative investors who are averse to large drawdowns. We do not argue against owning equities selectively; indeed, we can still identify numerous pockets of attractive opportunities for active and well-researched investors. However, unquestionably a real need for great active management, a risk management focus and differentiated portfolio management. Why Modest Portfolio Management is Now More Important than Modern Portfolio Theory The only thing we know for sure is that we don't know for sure. Hence, it is crucial - no matter what we believe about anything - that we diversify our portfolios and our risk-taking. Of course, we can and should make significant probability-based assessments about the future, and if you are good at this, we can do so with some accuracy, but we should never forget that we can't predict the future per se. Hence, the main reason to be confident in my (or another) portfolio is not only because my research and judgment or opinion are accurate or useful, but that I will be sensibly diversified among numerous attractive active strategies. This diversification is no longer available in a portfolio by simply buying bonds to offset equities, or indeed by owning a few typical equities. By being better diversified you narrow the range of realistic return outcomes and create a better, more consistent, and more tolerable journey for your capital and peace of mind.

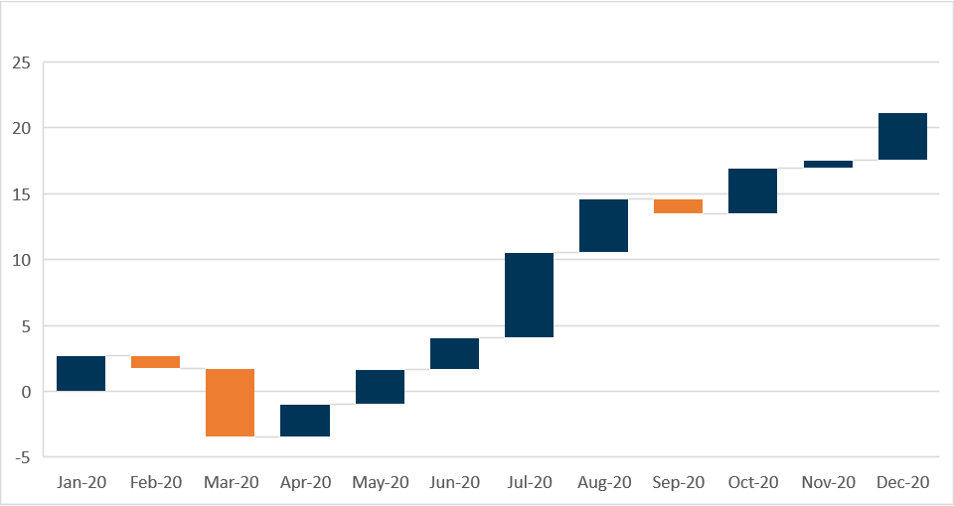

The "TINA" alternative crowd is overly narrow in its focus and overly confident by definition. There are many alternatives out there other than simple equities. Furthermore, in no small part because of all the inefficiencies and craziness in markets today, some of these alternative strategies are extremely promising and attractive investments - we consider many to have more than 10% outperformance potential compared to more commonly held investments. These opportunities are scarce and not easy to identify and will routinely be overlooked by the mainstream because they require a specialist skill set, training, and specialization to invest in well. Simply buying any alternative is no guarantee of success. Wholesale investors - such as those with SMSFs - have the potential opportunity to access the best alternatives because they are often only made accessible to wholesale investors. Wholesale investors should hence ensure that they are not missing out on these opportunities or being treated as retail investors and realizing much lower risk-adjusted returns than they should be. For those who can put themselves in a position to access it, a well-run and actively managed diversified alternative portfolio is a truly great alternative to being all-in on anything. Its results are also measurable and should speak for themselves over time with superior risk-adjusted returns. It is a better way to reduce cash and bonds without being overly concentrated on the same risks, as well as a great complement to investors' existing property portfolios. It is not without any risk - nothing is - but importantly, it has different risks and diversification greatly helps mitigate the risk of any individual strategy. Furthermore, while alternatives help reduce portfolio risk, they don't have to mean low returns. By way of example, during the turbulent 2020 calendar year, Dr. Jerome Lander was Portfolio Manager for an alternatives fund that achieved a net return of 21.13% with low volatility (circa 5%). This strong return compares favorably to single-digit returns across many asset classes including typical diversified funds such as large super funds during the same period (which was a historically important crisis period because of COVID-19). Alternative Fund Performance in 2020 - Net Return to Investors (%) 21.13% Total Net Return (Calendar Year 2020, LAIF)

Data Source for returns: LAIF, Mainstream fund services. LAIF is owned by a different firm and has different objectives and fees to the WealthLander Diversified Alternative Fund. The presentation of this information is designed to convey the quality of Dr Jerome Lander's work, not the performance potential of the WealthLander Diversified Alternative Fund. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. An active alternatives portfolio with an absolute return objective is aligned to what many investors want. It is designed around what matters most to many investors and quite possibly to you too as an investor. It targets lower volatility, lower drawdowns, and double-digit returns per annum, which is much higher than a traditional portfolio can expect - despite the lower market risk. It can even massively outperform equities as I did last year, particularly over a full cycle, given its lower drawdowns facilitate better long-term compounding. It has real return prospects unlike those of cash and bonds and its drawdowns should be tolerable and relatively quickly recovered from. The greater consistency, smoother return profile, and quicker recovery from drawdowns have a real benefit to investors, as it protects investors from buying high and selling low - which we know they are prone to do with many other strategies. It removes the fear factor of buying at the wrong time and immediately being exposed to huge losses from a market collapse. Conclusion It is necessary to adapt and alter investment behavior to changing market circumstances for investors to thrive and survive going forward. Traditional assets now have low long-term return prospects and could do anything in the short-term. There is a desperate need for a better-diversified portfolio in a world of potentially rising inflation. While cash and bonds offer poor return prospects and the need for alternatives is clear, being overly concentrated in long-only index-like equities at a time of great speculation could easily be considered imprudent, unprofessional, or at the very least, overly confident. A better-diversified portfolio provides different sources of returns to investors, including substantive and meaningful active management. It provides investors with much-needed exposure to incredibly attractive, differentiated, unique, and non-market-dependent opportunities. Although there is more than one alternative, it is the alternative that matters, and which is necessary today. Funds operated by this manager: |

30 Nov 2021 - Dissecting one of Berkshire Hathaway's greatest purchases - BNSF

|

Dissecting one of Berkshire Hathaway's greatest purchases - BNSF Datt Capital 08 November 2021 Disclaimer: This is a high level conceptual exercise and all figures are approximations using the CY2020 accounts. Funds operated by this manager: |

|

Disclaimer: This article does not take into account your investment objectives, particular needs or financial situation; and should not be construed as advice in any way. The author holds no exposure to the stock discussed |

30 Nov 2021 - Global equities market update and outlook for 2022

|

Global equities market update and outlook for 2022 Bell Asset Management 28 October 2021 |

|

|

Bell Asset Management Chief Investment Officer, Ned Bell discusses key themes that will influence global equity markets in the year ahead: geopolitics, global monetary policy, the economic cycle rotation and company earnings as well as responsible investing. Ned also looks at where the opportunities for investors may arise in 2022 and a look back at the lessons from this year.

|

29 Nov 2021 - Managers Insights | Glenmore Asset Management

|

|

||

|

Damen Purcell, COO of FundMonitors.com, speaks with Robert Gregory, Founder and Portfolio Manager at Glenmore Asset Management. The Glenmore Australian Equities Fund has a track record of 4 years and 5 months and since inception in June 2017 has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index, providing investors with an annualised return of 25.68% compared with the index's return of 9.84% over the same time period.

|