News

15 Aug 2022 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Hyperion Global Growth Companies PIE Fund | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Man AHL Alpha (AUD) - Class B |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Terra Capital Green Metals Fund | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| The Elvest Fund | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 700 others |

15 Aug 2022 - Four in five advisers have consulted clients about inflation in the last six months

|

Four in five advisers have consulted clients about inflation in the last six months abrdn July 2022

The vast majority (85%) of advisers have spoken with their clients in the last six months about how to adapt their finances or portfolios in the wake of soaring inflation, according to new research from abrdn. A fifth (22%) of advisers have spoken to all of their clients about the impact of inflation on their finances, while just one in ten (12%) have yet to discuss changes with any. To help clients manage the effects of inflation, advisers are most frequently altering pension drawdown strategies to reduce tax liability (23%) and adapting their investment portfolio to decrease risk (21%). More than one in six (17%) have also discussed a wider range of annuity options, while 14% have adjusted retirement income plans. abrdn's research also looked at advisers' client conversations about higher taxes, market volatility and the ESG implications of holding or making investments in Russian-linked assets following its invasion of Ukraine. A majority (85%) of advisers have discussed the impact of market volatility, 84% have discussed Russian-related ESG considerations and 83% have spoken to their clients about managing the impact of higher taxes. Jonny Black, strategic director abrdn, Adviser, said: "Advisers are yet again supporting clients in another challenging environment. Many will not have experienced the record levels of inflation we're currently living through, and I'd expect to see more people seek professional advice for the first time this year. "People want to know how to mitigate the impact of inflation on their finances, but also to better understand why the economy is in this position in the first place. This underlines the value of advice. Advisers help clients answer the hard, technical questions, but also help put their minds at ease in difficult times." When it came to the impact of Russian-linked ESG considerations, advisers have most frequently been working with clients to adjust retirement income plans (21%) and divest money away from Russian-linked assets, as required by sanctions (20%). Meanwhile, a further one in six (16%) advisers said they had divested client funds from Russian-linked assets out of clients' personal choice. Elsewhere, to help clients manage the impact of higher taxes, one fifth (20%) of advisers say they've increased the proportion of investments in a tax wrapper. A further 20% have altered their investment portfolio asset allocation to increase risk and potential return to mitigate the impact of market volatility. Jonny Black added: "It's clear both advisers and clients are taking a range of actions. With further challenges ahead - including warnings of worsening inflation - firms will need to be prepared to continue engaging with clients to ensure they're able to adapt to pressures and remain on the strongest possible financial footing." |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Aberdeen Standard Actively Hedged International Equities Fund, Aberdeen Standard Asian Opportunities Fund, Aberdeen Standard Australian Small Companies Fund, Aberdeen Standard Emerging Opportunities Fund, Aberdeen Standard Ex-20 Australian Equities Fund (Class A), Aberdeen Standard Focused Sustainable Australian Equity Fund, Aberdeen Standard Fully Hedged International Equities Fund, Aberdeen Standard Global Absolute Return Strategies Fund, Aberdeen Standard Global Corporate Bond Fund, Aberdeen Standard International Equity Fund , Aberdeen Standard Life Absolute Return Global Bond Strategies Fund, Aberdeen Standard Multi Asset Real Return Fund, Aberdeen Standard Multi-Asset Income Fund

Methodology Survey of 424 UK-based adult financial advisers, conducted by Censuswide on behalf of abrdn in May 2022. Notes to Editors At abrdn, our purpose is to enable our clients to be better investors. abrdn plc manages and administers £542 billion of assets for clients, and has over 1 million shareholders. (Figures as at 31 December 2021) Our business is structured around three vectors - Investments, Adviser and Personal - focused on the changing needs of our clients. For UK wealth managers and financial advisers, we provide technology, expertise and support to make it easy for them to run their businesses - and to deliver the outcomes their clients want. We offer content and experiences that can be personalised to suit every type of business and client, giving advisers powerful data and insight to make better decisions. We're the number one adviser platform business in the UK for assets under administration and gross flows (Adviser AUA: £76 billion as at 31 December 2021). We're also the first UK adviser platform provider to receive and retain an 'A' rating from AKG for the financial strength of our platforms (AKG financial strength reports 2021).

|

12 Aug 2022 - Why are we so afraid of normal?

|

Why are we so afraid of normal? Yarra Capital Management 25 July 2022

Dion Hershan, Head of Australian Equities, details why he believes the panic in markets today appears excessive. There has been an extreme bout of panic this year (ASX -11%, S&P 500 -19%) regarding the return of what appears to be a traditional business cycle (yes it still exists!) and key settings normalising. With the glory years of low and falling interest rates (supplemented by a bit of QE) now over, financial markets are in a state of flux. This is notwithstanding the obvious inevitability that at some point interest rates would have to move upwards from zero! Commentators, many of whom just finished becoming experts on epidemiology, are now opining on the chance of a recession and discussing it as if it's a fatalistic event. It is worth noting the US had 12 recessions in the 20th century and still fared OK. Unfortunately there appears to be no sensible discussion about the duration or severity of a recession, instead just alarmist rhetoric. While we won't attempt to call the business cycle, we do believe it's worth sharing a few simple facts with reference to the Australian market where we focus:

Financial markets always look forward and often overreact. This sell off has put forward earnings multiples at 12.5-times, the lowest level since the GFC (one standard deviation below the long-term average). Clearly, broad based earnings downgrades are expected in August; a 20% downgrade would put the market at 'fair value', which may very well happen. For what it's worth, we believe this feels like a forced slowdown in the economy and the panic that has ensued seems excessive. We are capitalising on the opportunity and stepping up at the epicentre of the panic to buy a number of quality cyclical and high growth business. We have established a position in Xero (XRO) which has halved and has enormous runway for growth (new markets, lifting average spend) and also increased positions in Carsales.com (CAR), Reliance Worldwide (RWC), and Nine Entertainment (NEC). |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Yarra Australian Equities Fund, Yarra Emerging Leaders Fund, Yarra Enhanced Income Fund, Yarra Income Plus Fund |

11 Aug 2022 - Fundmonitors.com Spotlight Review - Top Performing Australian Small/Mid Cap Managed Funds

|

Fundmonitors.com Spotlight Review - Top Performing Australian Small/Mid Cap Managed Funds FundMonitors.com 10 August 2022 |

|

This FundMonitors research article puts the Spotlight on the performance of Australian Small/Mid Cap Sector over the Financial Year to 30 June, 2022. Following the Covid downturn in March 2020, the sector gained popularity with Australian investors as they looked for the significant opportunities the small cap sector can produce. However the last 12 months has, to use a sporting analogy, been a game of two halves, with the strong performance from July to December 2021 coming to a grinding halt in January 2022. This has seen some small cap stocks reduced to prices below their cash value as noted by Dean Fergie of Cyan Investment Management in a recent Fund in Focus video. As a result, many active small and mid cap funds struggled to provide positive returns in FY 2022. There may be multiple reasons for this, most of which are covered in this video, for investors and managers alike it was a tough and disappointing six months. The graph below shows the distribution of fund returns for the Small/Mid Cap Peer Group on Fundmonitors.com over the 12 months to June 2022. Of the 80 funds included in the group, just 4 managed to post a positive return, with 24 failing to outperform the index. However, the Australian Small/Mid Cap Peer Group as a whole outperformed the S&P/ASX Small Ordinaries Index over the last 5 and 10 years on a cumulative basis. The graph below shows the performance of the entire peer group over 5 years to June 2022, again highlighting the strong rally from April 2020 after the initial Covid shock, and the downturn since December 2021 as increased interest rates adjusted valuations, followed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine in late February. Given the wide variance in individual fund performances, clearly manager and fund selection is a crucial decision, even though the peer group average produced better performance than the underlying index over time. However, this is not as easy as choosing the best performing fund from the latest league table, as shown by the table below showing the Top 25 performing funds for the 12 months to June, 2022, and their performance in previous years: A key point to note is the position of funds in the table each year. Of the top 25 performing funds in the 21/22 Financial year, none appeared in the Top 25 list across all 5 years. Only 4 of them, namely Glenmore Australian Equities Fund, DMX Capital Partners Limited, Nikko AM Core Equity Fund (NZ) and the Ausbil MicroCap Fund, appeared in the Top 25 in four out of five years. Importantly, or perhaps disconcertingly, each of these funds ranked in the bottom 25 performers at least once over the 5 year period. In spite of this, and with the benefit of hindsight, an equal investment in each of these four in July 2017 would have resulted an attractive annualised return of 14.56% over 5 years, albeit with a drawdown of almost 30% in February and March 2020 as Covid hit. While it is a useful exercise to understand which funds have performed best over each 12 month period, the table below shows the Top 25 funds over various time frames, ranked by their 5 year performance. There are some familiar names from the previous table. It is also important to note that 6 funds in Top 25 over 5 years also ranked in the bottom 25 in the 12 months to June 2022. Consistency, particularly given a period with 2 separate downturns - Covid in 2020, and then inflation led increases in interest rates in 2022 - has been difficult to achieve. Given the volatility of the past 3 years in particular, is it also worth considering fund performance based on both a risk and return basis. The following chart shows the top 25 Funds over the past 3 years with their maximum drawdown shown in red. The small and mid cap sector is particularly affected by sharply falling markets when liquidity is reduced, or in a worst case environment, evaporates. Notably, a number of funds that performed well across multiple timeframes have derived their performance in different ways. The DMX Capital Partners Fund was the strongest performer over 3 years primarily as a result of having one of the lowest drawdowns in the peer group, with a Down Capture Ratio of just 51.47. Conversely, the Perpetual Pure Microcap Fund was 7th over 3 years, but with a maximum drawdown of -41.41% it had to rely on an Up Capture Ratio of 147.67 to achieve its position in the Top 10. Conclusion As much as investors, analysts and research houses enjoy the idea of lists of top performing funds, our research has consistently shown that investing in last year's Top 10 does not result in top performance in the following year! In spite of this the natural tendency of investors to chase top performing funds over a short time frame continues, often with disappointing results. So if 12 month performance is not a reliable indicator of a fund's future performance, what is the optimum time frame, or are there other key indicators involved in fund selection? Every fund's offer document contains the disclaimer that "past performance is not a guarantee….. " but every investor looks for a manager's track record as a guide. Making it equally difficult for the investor and advisor is the strong evidence that managers and funds with a track record of under three years outperform their larger peers with a longer track record. There is no clear cut answer - just as there is no clear cut "best" fund or manager. Undoubtedly diversification reduces risk, but potentially it also potentially dampens returns as well. Fund selection and portfolio composition will therefore depend on each investor's risk and return (R&R) profile, itself complicated by the fact that investors' R&R profile changes over time in line with the market outlook. The most obvious (or frustrating) conclusion from the data is that selecting funds with the benefit of data and hindsight is simple, but sadly in real time it is not so easy! All data produced in this report was sourced from the Fundmonitors.com database which provides information on over 700 actively managed funds. Funds can be selected across Peer Groups, multiple sectors and geographies, with tools that enable investors and financial advisors to search and compare funds, run custom reports and create and analyse portfolios. For more information on Fundmonitors.com please click here. Disclaimer: All information in this FundMonitors.com Sector Spotlight is believed to be correct at the time of publication. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns, and investors should make their own enquires and conduct research on any fund prior to making an investment decision. Nothing in this report should be considered as a recommendation for any fund named herein. |

11 Aug 2022 - Challenges and opportunities for global equities: Insights from our recent US research trip

|

Challenges and opportunities for global equities: Insights from our recent US research trip Bell Asset Management July 2022 |

|

|

With global equity valuations coming under pressure due to surging inflation, rising interest rates and elevated commodity prices, the outlook for investors continues to provide uncertainty. On a recent research visit to the US, Portfolio Manager, Adrian Martuccio sat down with various portfolio company management teams to discuss their outlook and business confidence, as well as the impact of inflation on consumer demand and supply. We share a summary of his views and unpack some of the ideas and themes that were addressed. Despite the ongoing list of negatives that investors are facing, there are still a number of positive items that support 'quality' when it comes to taking a long term view on global equities. US insights - what you need to know As we look at the state of the US economy, global company management teams exhibited similar viewpoints about the high likelihood of a recession with the vast majority being more sanguine that a slowdown/recession will ease supply chain bottlenecks. Many businesses believe that supply chain issues are still widespread, primarily labour driven with smaller companies, though these backlogs will likely decline by the end of the year as inventory gets replenished. As recession uncertainty continues, sectors such as manufacturing and selective retail are seeing elevated inventory levels becoming the heart of the problem in their businesses, partly due to growing backlogs, long transit times and over-ordering. Concerns are also mounting about the impact of escalating inflation levels, which has seen the US reach a 40 year high inflation level of 9.1% in June 2022. According to Adrian Martuccio, employee shortages are rife across the nation and inflation continues to be well anchored compared to last year. While investors adjust their expectations of the inflationary pressures they face, we believe that US household and bank balance sheets remain healthy. One thing is certain, a combination of soaring inflation, slowing growth and high company margin expectations is taking place, as the hiking of interest rates on equity valuations evolves into investor worries. The consensus is that company forecasts need to come down and margins across the board are far too high. Management teams believe that stock prices have factored this in, but we believe it will become difficult for companies to rally convincingly in the face of downgrades - with investors now questioning whether company earnings will moderate as both demand and margins come under pressure. Growth sectors under pressure Software and biotech industries, once lucrative and heavily weighted growth sectors, have seen valuations come under significant pressure in the listed space and private companies are now experiencing funding drying up. We believe valuations in the private space will further reduce once companies in these sectors become desperate for the next round of capital inflow or when venture capitalists decide to exit. The US is already entering a new phase of a downturn, and it's expected that there will be plenty of 'down-rounds' that will become painful from an investor's perspective. Regardless of the fact that slower or negative growth has increased materially for information technology sectors, many tech startups are starting to experience job losses as they try to reduce the bleeding of cash. It was evident from our discussions that many larger tech companies that have recently struggled to attract talent due to many startups offering stock (which are now deeply underwater as stock prices plummet),and are finding more talent coming to the market wanting a new and stable job. This instability in the US jobs market, not just in software/cloud but consumer companies, is becoming more challenging as companies find that they need to be rational with their decisions to pivot and sustain their businesses. A snapshot of how the US and global economy is performing as it signals a historic downturn

Capturing 'Quality' in a volatile and uncertain market This year's global market correction reflects several concerns about the economic future. From a stock perspective, sharp declines across equity portfolios are putting investors under severe pressure to hold long-term return potential. In our experience, lower volatile portfolios focused on high quality companies with low levels of debt and high cash flow are an essential indicator of 'Quality'. They have the potential not only to provide superior risk-adjusted returns, but they may also exhibit defensive characteristics in times of market volatility. We expect that 'Quality' as a style will generate material alpha in this current environment. How are we positioned in this environment? Our portfolios remain fully invested, and whilst we adjust our expectations for this evolving environment, our 'Quality at a Reasonable Price' or 'QARP' style (investing in high quality businesses while not overpaying for them) we believe our valuation discipline has and will continue to hold us in good stead in challenging periods. As the market experiences further weakness, there are several opportunities that we have been following and we will likely see more eventuate throughout 2022. Investors should always remember that economic downturns aren't forever and should take a long-term view on their global equities which will help to position their portfolio for an uncertain future ahead.

|

10 Aug 2022 - Australian Secure Capital Fund - Market Update July

|

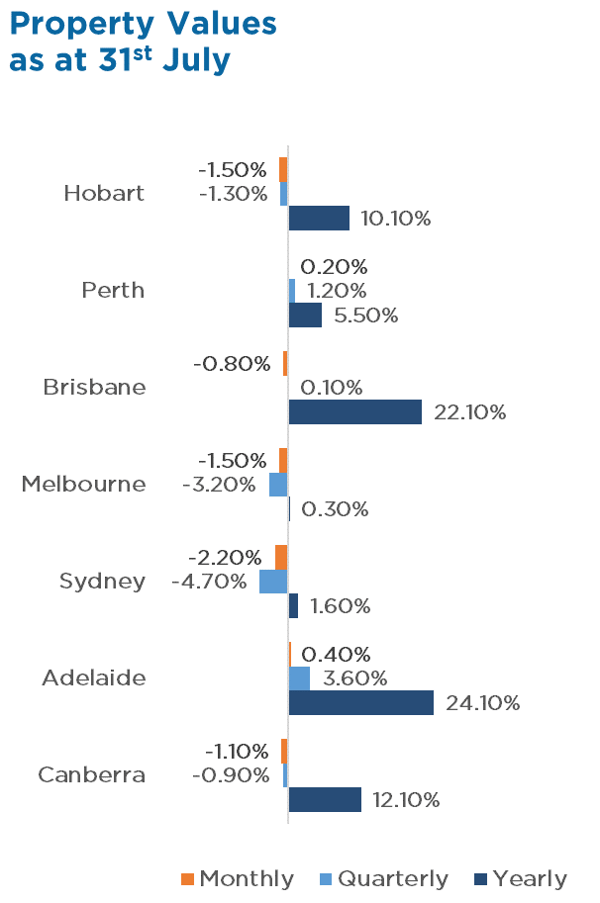

Australian Secure Capital Fund - Market Update July Australian Secure Capital Fund July 2022 Australian residential property values fell by 1.3% in July bringing the total quarterly decline across the country to -2%. Inventory levels have also decreased significantly and have now fallen -21.40% from the mid-March peak, helping to keep overall inventory levels low whilst on the demand side sales activity over the three months to July was -16% lower in comparison to the same period last year. While national home sales are also falling from record highs, they are still +9.20% above the previous five-year average for this time of year. With interest rates expected to rise further, there is a good chance that the number of transacted sales will continue to fall as confidence continues to weigh on the housing sector. On a more positive note, however, rents across the country continued to increase through July rising +0.90% for the month to be +2.80% higher for the quarter and +9.80% higher over the past 12 months.

Funds operated by this manager: ASCF High Yield Fund, ASCF Premium Capital Fund, ASCF Select Income Fund |

10 Aug 2022 - Holding your discipline

|

Holding your discipline Airlie Funds Management July 2022 |

|

Portfolio Managers John Sevior and Matt Williams have worked together in funds management for more than 30 years. In this session, they discuss what it's like to invest in the current market and how it compares with past 'extreme market conditions'. In addition, they assess which ASX companies could perform in these conditions. Speakers: Matt Williams, Portfolio Manager Funds operated by this manager: Important Information: Units in the fund(s) referred to herein are issued by Magellan Asset Management Limited (ABN 31 120 593 946, AFS Licence No. 304 301) trading as Airlie Funds Management ('Airlie') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should obtain and consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement ('PDS') and Target Market Determination ('TMD') and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making a decision to acquire, or continue to hold, the relevant financial product. A copy of the relevant PDS and TMD relating to an Airlie financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4760 or by visiting www.airliefundsmanagement.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any financial product or service, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to implement its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of an Airlie financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Airlie makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Airlie. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any third party trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and Airlie claims no ownership in, nor any affiliation with, such trademarks. Any third party trademarks that appear in this material are used for information purposes and only to identify the company names or brands of their respective owners. No affiliation, sponsorship or endorsement should be inferred from the use of these trademarks.. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Airlie. |

10 Aug 2022 - Could a credit crunch be more important than a recession?

|

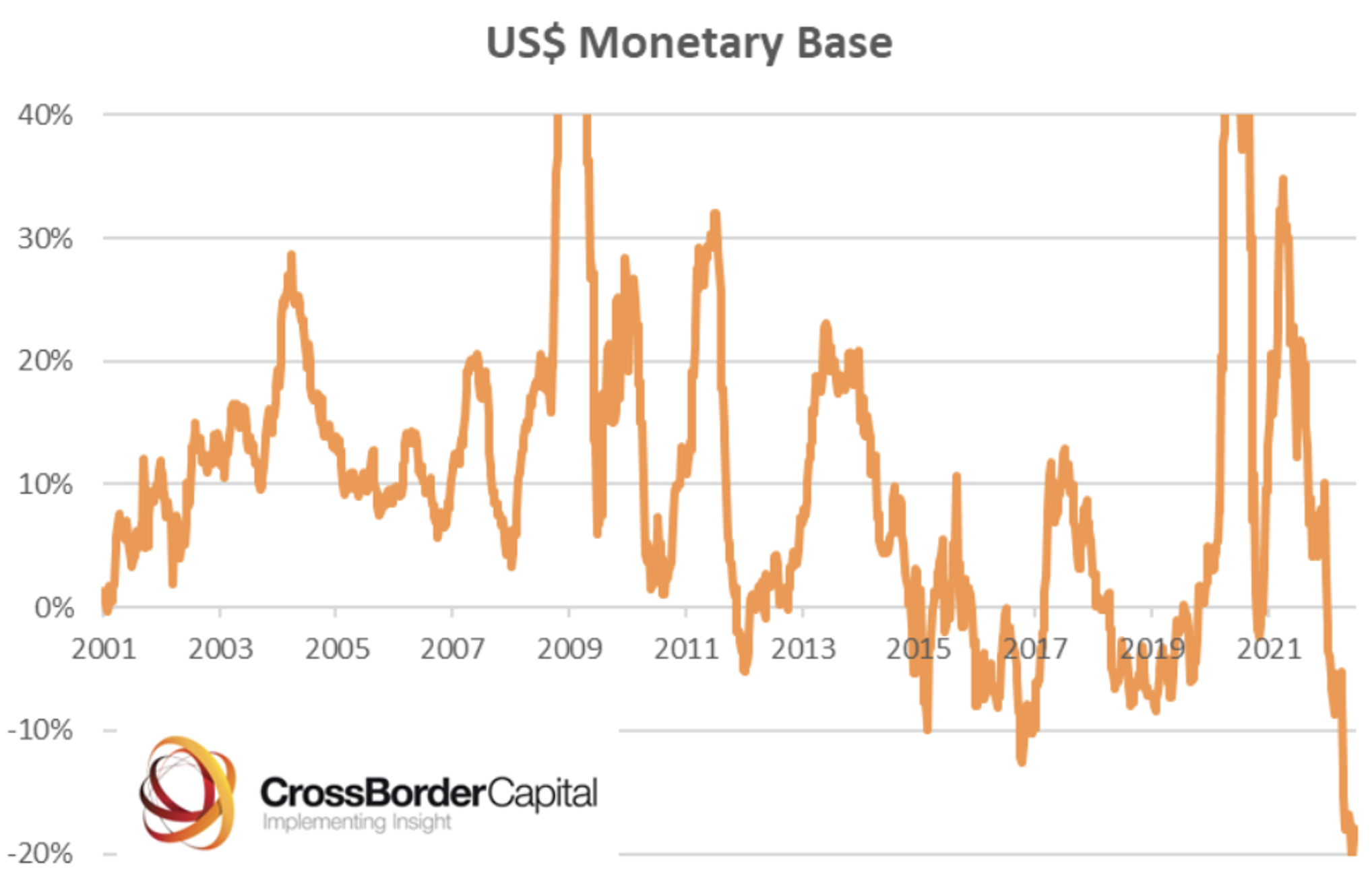

Could a credit crunch be more important than a recession? Montgomery Investment Management 20 July 2022 Some say its two quarters of negative growth. If that's the case, then the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow tool is predicting the U.S. is in a recession. Meanwhile, the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research says a recession is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. If that's the case the 488,000 new jobs created in May would void any assessment of recession. Elsewhere, given inflation is at nine per cent in the U.S., and growth is a far cry from that number, the real economy is going backwards, validating the person-in-the-street's perception of recession. And finally, the U.S. yield curve has just gone negative, confirming an economic slowdown. Central banks are in a quandary Even though economies appear to be losing momentum, inflation remains unacceptably high. And even though we might be near a peak in inflation, the decline is unlikely to be fast enough to placate Central Banks. Consequently, I agree with the idea downside surprises in inflation are the outcome of recession, not an indicator we will avoid one - whatever your definition of recession actually is. The last time U.S. inflation was this high was 1981, but as analyst Ben Carlson points out the circumstances are very different. In 1981, savings accounts offered a 10 per cent yield (today they provide a one per cent yield). Mortgage rates then were 17 per cent, today they are five per cent. In 1981 U.S. treasury bond yields were 13 per cent, today they are at three per cent. And finally, Robert Shiller's Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio was just eight times in 1981. Today it's still at 28 times. There are a multitude of differences today to any other time in history. Searching the past to discern what happens next may be a fools errand. Instead, I believe it is most important to look to liquidity. Giant swings in the availability of money, especially in modern debt-based financial systems, do more to explain the vicissitudes of markets than macroeconomics. And on that front, Crossborder Capital's chart of the liquidity cliff in the supply of the USD worldwide, including off-shore, suggests a major credit crunch is ahead.

Source: Crossborder Capital And according to Michael Howell, "The economic cost of this big liquidity squeeze is world recession" adding "Central Banks are making a major error by hammering down too hard on the brake. World recession is inevitable." Meanwhile the U.S. Treasury yield curve is seeing collapsing term premia. The term premium is the amount by which the yield on a long-term bond is greater than the yield on shorter-term bonds. Collapsing premia means short term rates are rising at a higher rate than long term rates. The mix of higher front-end rates raises cost of capital for corporates, while lower rates at the long end of the yield curve reflects meaningful demand for safe assets. In other words, no appetite for riskier corporate debt. In combination, it suggests a credit crunch is afoot. It's arguably much more important than whether we are heading for a recession - whatever your definition. Author: Roger Montgomery, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer Funds operated by this manager: Montgomery (Private) Fund, Montgomery Small Companies Fund, The Montgomery Fund |

9 Aug 2022 - Activism by prominent Australians

9 Aug 2022 - Will falling house prices tip Australia into a recession?

|

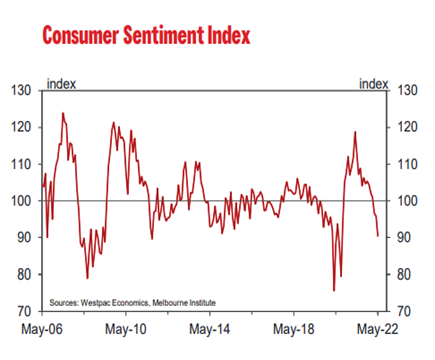

Will falling house prices tip Australia into a recession? WaveStone Capital 25 July 2022 With the RBA tightening cycle firmly underway, the impact for Australian households is only starting to be felt. Dwelling prices are falling most notably in Sydney and Melbourne where 39% of households reside but have 53% of total housing debt1. The pace of rate hikes is at levels not seen since 1994 and combined with rising energy costs and higher food prices it is not surprising that consumer sentiment has fallen sharply as shown in the chart below.

What does this mean for consumer spending and is a recession on the cards?Relative to other developed markets, Australia's economy has been strong; boosted by high commodity prices, lower relative interest rates, a weak Australian dollar and solid household balance sheets. A lower exposure to long duration technology stocks (which have been hardest hit) has also provided some insulation from the global equity sell-off. For the six months ending June 30, 2022, the total return for ASX300 is -10.4% compared to -20% for the S&P500 and -20.3% for MSCI World. Looking forward from here, vulnerabilities are apparent and none more so than in the housing market. Having spoken to bank executives, real estate businesses and developers over the past year, we expect a contraction in the housing market. The evidence is mounting even though price falls have been modest thus far.

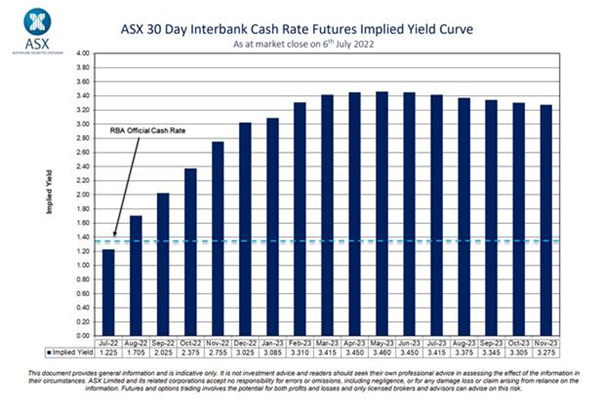

However, in our view, the outlook is not as grim as media reports would suggest with a fall of 15% likely over the next 18 months. This is due to the expected influx of immigration now that borders are open as well as the structural shortage of housing stock which puts a floor on house prices. While a 15% fall in the housing market would be material, there is also a wealth effect to consider. The magnitude of the hikes is massive at the margin. Even for those who do not face mortgage stress, higher mortgage payments dent consumer confidence and spending. The consequences are wide-reaching with impacts for the banking sector, construction, and ancillary businesses such as law firms and architects. Further, there is a significant refinancing event looming in 2023 as a large swathe of fixed rate loans roll off and many households will face a 40% increase in their repayments as they move to variable rates (based on current rates). History teaches us that tightening cycles usually lead to a de-rating of P/E multiples for the banking sector. While steady interest rate rises are seen as a positive tailwind, with every 25bps increase leading to a 1-2bps positive boost to net interest margins, the sheer pace of the current increases creates a different outlook. While the banking sector is already down by 10% since the start of June, and has underperformed the broader market, looking forward the downturn in the housing market will lead to lower credit growth, lower margins and higher bad and doubtful debts. According to Jarden Research, new home growth leads bank share prices by approximately 3 months and bank share prices lead house prices by 5 months given the lag in house price data and the forward-looking nature of markets. A de-rating of major bank share prices occurred in Australia during the 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 cycles when multiples fell by an average of 2.0x in the first three months after the first hike and 4.2x by the time of the last hike2. New Zealand, which is further ahead of Australia on rates is already experiencing a slowdown in credit growth. While Australian banks are well capitalised with very strong balance sheets, the medium-term outlook for their share prices will be negatively impacted by a housing downturn. A slump in consumer discretionary spending is expected as households tighten their belts. The question for investors is how much of this is already priced in? Many stocks in this sector have already fallen significantly as consumers have shifted their spending from goods to services and earnings have normalised. Despite this, in our view, the consensus forecasts for FY23 and FY24 are still too optimistic. We have not seen earnings downgrades yet and this could occur in the coming weeks. While reporting season is likely to show strong results on a historical basis, analysts will focus their attention on forward looking guidance for earnings - or lack thereof. For retailers, in addition to the rising cost of debt, analysts will be watching inventory levels. In many cases, inventory levels have been rising as supply chain issues ameliorate and are indicative of falling demand. The US provides a good indicator of the outlook for Australia given their rate hiking cycle and emergence from pandemic lockdowns is about 6 months ahead of Australia. What is evident is that retail is struggling with rising mortgage costs impacting consumers spending patterns. This is most evident for furniture, electronics and hardware sales which are highly correlated with housing growth. Whether or not we get a recession in Australia will depend largely on how aggressive the RBA is in raising rates. A neutral rate of 2.5% for example would dramatically impact borrowing capacity. Future inflation prints will determine whether the RBA stops there, and time will tell whether the current level of pessimism is overdone. As shown in the chart below, the market is expecting rates to peak in May 2023 with softer economic growth leading to rate cuts thereafter.

We have assessed the implications of a downturn in the housing market and falling consumer spending for investee companies on a bottom-up basis. We are underweight sectors such as financials and property trusts as well as those retailers more likely to be impacted by lower discretionary spending. We have long been overweight healthcare, which has proven to be resilient in previous downturns. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: WaveStone Australian Share Fund, WaveStone Capital Absolute Return Fund, WaveStone Dynamic Australian Equity Fund 1 Source: Macquarie, July 20222 Source: Morgan StanleyThis material has been prepared by WaveStone Capital Pty Limited (ABN 80 120 179 419 AFSL 331644) (WaveStone). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed. |