News

19 Jan 2024 - Trip Insights: The US

18 Jan 2024 - Australian Fixed Interest: Unveiling the road ahead in 2024

|

Australian Fixed Interest: Unveiling the road ahead in 2024 Janus Henderson Investors December 2023 Bond markets have experienced a heightened level of volatility and recent drawdown having emerged from a period of exceptionally low yields. In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the pandemic, policy makers tested zero and even negative yields in a bid to fight the low growth, low inflation environment with artificial and extraordinary central bank interventions. Today, in a bid to fight the exact opposite, policy has again driven yields to new post GFC highs. Market participants now readily accept, for a variety of reasons including the great energy transition, 'friend-shoring' and geopolitics, that inflation and therefore yields are likely to be higher on average over the decade ahead. However, what perhaps is missing in this view is that cycles can still co-exist amongst these structural trends. The next year is one where we believe the cycle will come to the fore. Macro themes in an uncertain futureThe macro environment as we enter 2024 looks to be uncertain and uncomfortable future, and one in which things are likely to come to a head. Our central case sees a slow deflation of the excess demand meeting limited supply difficulties, but there are a myriad of risks. We believe the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will be on hold through most of 2024, with a modest easing cycle commencing late Q3 next year. GDP growth will remain below trend, and weakness will progress from households through to the investment side of the economy. Finally, we think inflation will moderate back towards, but not quite reaching, the RBA's 2-3% target. Strong population growth and housing dynamics risks further RBA tightening, but this is balanced against the pressures generated from the 4.25% tightening seen so far. Population growth should ease up to the pre-pandemic trend. We see the slowing economy leading to a slowly rising unemployment rate, which will move the economy back toward equilibrium. Downside risks come from slowing global growth, and China in particular. Geopolitical pressures are also being watched closely, as they have the potential to weigh on growth and push inflation higher. Locally, we watch for cracks in spending and the path of fiscal policy. Markets on the other hand have toyed with the 'higher for longer' and 'policy likely to grip' themes. Today the market has very little priced in terms of an easing cycle, with an average cash rate over the next half decade of 4 to 5% and even a little higher over the subsequent 5 years. This, in our assessment, is unlikely to be validated by the RBA over time. Meanwhile corporates are facing a more challenging environment after having enjoyed a couple of years of above-average profits buoyed by ultra cheap debt funding costs, an ability to pass through cost inflation and having benefited from strength in nominal revenues. In 2024, these very corporates are likely to face a constrained consumer, ongoing cost pressures and elevated refinancing costs. It will be a year of the haves and have nots in the corporate space; those with prudent balance sheet management in resilient industries separated from others exposed to consumer cyclical, interest rate sensitive industries. Investment grade companies for the most part remain well placed to weather an economic slowdown. Lower credit quality segments (and in particular leveraged companies, related to construction, housing, non-conforming asset backed securities and consumer finance) stand to be tested in the year ahead, at the very least with mark to market drawdowns but potentially with permanent loss of capital for investors. With the cycle maturing, our preference is to be concentrated in higher quality credit which remains the sweet spot for investors with equity like return prospects. We remain wary of the more complex, levered or subordinated credit segments, especially those lower in quality. In seeking opportunities, we remain patient as we seek meaningful future high yield, loan and emerging market debts. The road aheadLooking to 2024, the fixed interest asset class provides a compelling proposition as a genuine diversifier with attractive yields offering strong competition to a number of growth asset classes; a privileged position following years of the opposite. However, the latter stages of the economic cycle will likely deliver higher levels of volatility, creating opportunities for those investors who have to tools, skills and risk taking heritage to be able to take advantage of. In 2024, our 'north stars' remain that:

Author: Jay Sivapalan, Head of Australian Fixed Interest, Shan Kwee, Porfolio Manager and Emma Lawson, Fixed Interest Strategist - Macroeconomics |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Janus Henderson Australian Fixed Interest Fund, Janus Henderson Australian Fixed Interest Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Cash Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Conservative Fixed Interest Fund, Janus Henderson Conservative Fixed Interest Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Diversified Credit Fund, Janus Henderson Global Equity Income Fund, Janus Henderson Global Multi-Strategy Fund, Janus Henderson Global Natural Resources Fund, Janus Henderson Tactical Income Fund This information is issued by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited ABN 16 165 119 531, AFSL 444266 (Janus Henderson). The funds referred to within are issued by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Funds Management Limited ABN 43 164 177 244, AFSL 444268. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Prospective investors should not rely on this information and should make their own enquiries and evaluations they consider to be appropriate to determine the suitability of any investment (including regarding their investment objectives, financial situation, and particular needs) and should seek all necessary financial, legal, tax and investment advice. This information is not intended to be nor should it be construed as advice. This information is not a recommendation to sell or purchase any investment. This information does not purport to be a comprehensive statement or description of any markets or securities referred to within. Any references to individual securities do not constitute a securities recommendation. This information does not form part of any contract for the sale or purchase of any investment. Any investment application will be made solely on the basis of the information contained in the relevant fund's PDS (including all relevant covering documents), which may contain investment restrictions. This information is intended as a summary only and (if applicable) potential investors must read the relevant fund's PDS before investing available at www.janushenderson.com/australia. Target Market Determinations for funds issued by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Funds Management Limited are available here: www.janushenderson.com/TMD. Whilst Janus Henderson believe that the information is correct at the date of this document, no warranty or representation is given to this effect and no responsibility can be accepted by Janus Henderson to any end users for any action taken on the basis of this information. All opinions and estimates in this information are subject to change without notice and are the views of the author at the time of publication. Janus Henderson is not under any obligation to update this information to the extent that it is or becomes out of date or incorrect. |

17 Jan 2024 - Why self storage could be a good place to stash some cash

|

Why self storage could be a good place to stash some cash Pendal December 2023 |

|

Self storage is an under-appreciated part of the real estate industry that could be a big winner from Australia's growing population. Julia Forrest explains the investment opportunity. SELF-STORAGE is not the first place many investors would think of as a place to stash some cash. But Aussie equities investors looking for opportunities should take a closer look at the industry, says Pendal PM Julia Forrest. "The world of self-storage is not something you often hear about, but it's an asset class we like," says Forrest, who co-manages property investing in Pendal's Aussie equities team. Record high immigration and a downsizing trend towards apartment-living will fuel ongoing strength in the self storage industry, says Pendal's Julia Forrest. ASX-listed National Storage REIT (ASX: NSR) -- which operates 230 centres across Australia and New Zealand -- offers exposure to the sector. NSR is the biggest active position in Pendal's property strategy, Forrest says. The opportunity explainedHigh inflation and rising interest rates have seen a somewhat muted investor appetite for real estate over the past twelve months. Office assets are trading as much as 30 per cent below book value and the retail and logistics sectors are both under some pressure. But self-storage assets are defying that trend, underpinned by strong demographics, low maintenance costs and inbuilt inflation protection, says Forrest. "Occupancy was supercharged during COVID -- and is now returning to normal -- but the underlying metrics remain very strong, linked largely to Australia's strong population growth." Self-storage assets were in strong demand during the COVID lockdowns period as young people returned to the family home, expats were forced to return at short notice, and many households had to clear space for working from home. Now immigration and an ageing population are underpinning the industry's growth. Forrest says 70 per cent of self storage clients are individuals looking for somewhere to store their possessions, often prompted by a life event. The remaining 30 per cent are businesses needing somewhere to store their inventory, building materials, and tools. Low costs, strong pricesOne of self storage's key attractions is very low maintenance costs compared to other types of real estate. "It costs very little to maintain -- you're replacing lighting, there's a minor amount of depreciation. That means you get strong, resilient cash flows." As a result, valuations are holding up well as other real estate sectors come under pressure. Retail real estate faces structural headwinds from the move to online shopping and infinite supply of virtual alternatives to physical store space, says Forrest. Office is also facing structural change in the way people work and has risks ahead as the economy slows. "But self storage is not a discretionary purchase -- a lot of it is needs based because of those life events, which makes it a little more resilient than the other sectors. "Self storage is still transacting at book value. Office is 20 to 30 per cent below book value. Retail and even industrial are beginning to see a bit of pressure on book values, but self storage continues to transact at book values." Self-storage sites also have the potential for transformation into high value industrial and logistics space, she says. "Industrial vacancy is incredibly low. For self storage, one of the higher and better uses is as industrial. You don't get that with office because of zoning." Inflation protectionForrest says self storage offers a level of inflation protection in a portfolio because of the short duration of leases. "Because you're leasing month to month, if there is a big inflationary spike you can just lift your rate. You are not locked into a long-term lease. This provides quite a lot of inflationary resilience." She says the Australian market is quite immature relative to other markets. "Self storage space in Australia represents 2.1 square feet per capita. In the US, it's closer to 6.1 square feet per capita. So, in terms of available space, Australia is relatively under serviced, although the US is a much more mobile market." Real estate sentiment shiftsSentiment towards real estate has shifted markedly in the last few weeks after a tough year amid signs that inflation is coming under control, Forrest says. "Until very recently, people were very concerned about interest rates and inflation. "But with a couple of lower CPI readings here and in the US, the market's pricing of future rate hikes has come way back and that has led to a real estate rally." Author: Julia Forrest & Pete Davidson |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Pendal Focus Australian Share Fund, Pendal Global Select Fund - Class R, Pendal Horizon Sustainable Australian Share Fund, Pendal MicroCap Opportunities Fund, Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund - Class R, Regnan Global Equity Impact Solutions Fund - Class R, Regnan Credit Impact Trust Fund |

|

This information has been prepared by Pendal Fund Services Limited (PFSL) ABN 13 161 249 332, AFSL No 431426 and is current as at December 8, 2021. PFSL is the responsible entity and issuer of units in the Pendal Multi-Asset Target Return Fund (Fund) ARSN: 623 987 968. A product disclosure statement (PDS) is available for the Fund and can be obtained by calling 1300 346 821 or visiting www.pendalgroup.com. The Target Market Determination (TMD) for the Fund is available at www.pendalgroup.com/ddo. You should obtain and consider the PDS and the TMD before deciding whether to acquire, continue to hold or dispose of units in the Fund. An investment in the Fund or any of the funds referred to in this web page is subject to investment risk, including possible delays in repayment of withdrawal proceeds and loss of income and principal invested. This information is for general purposes only, should not be considered as a comprehensive statement on any matter and should not be relied upon as such. It has been prepared without taking into account any recipient's personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of this, recipients should, before acting on this information, consider its appropriateness having regard to their individual objectives, financial situation and needs. This information is not to be regarded as a securities recommendation. The information may contain material provided by third parties, is given in good faith and has been derived from sources believed to be accurate as at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, and while all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information is complete and correct, to the maximum extent permitted by law neither PFSL nor any company in the Pendal group accepts any responsibility or liability for the accuracy or completeness of this information. Performance figures are calculated in accordance with the Financial Services Council (FSC) standards. Performance data (post-fee) assumes reinvestment of distributions and is calculated using exit prices, net of management costs. Performance data (pre-fee) is calculated by adding back management costs to the post-fee performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Any projections are predictive only and should not be relied upon when making an investment decision or recommendation. Whilst we have used every effort to ensure that the assumptions on which the projections are based are reasonable, the projections may be based on incorrect assumptions or may not take into account known or unknown risks and uncertainties. The actual results may differ materially from these projections. For more information, please call Customer Relations on 1300 346 821 8am to 6pm (Sydney time) or visit our website www.pendalgroup.com |

16 Jan 2024 - Investing in toll roads

|

Investing in toll roads Magellan Asset Management November 2023 |

|

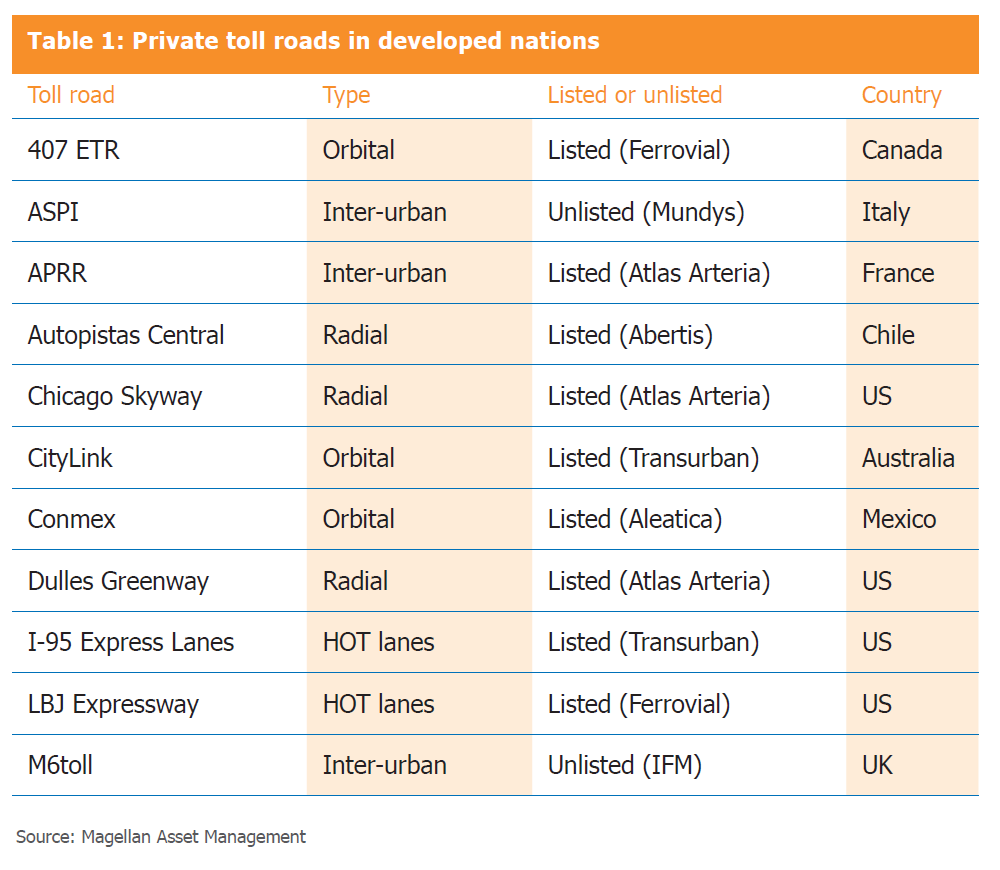

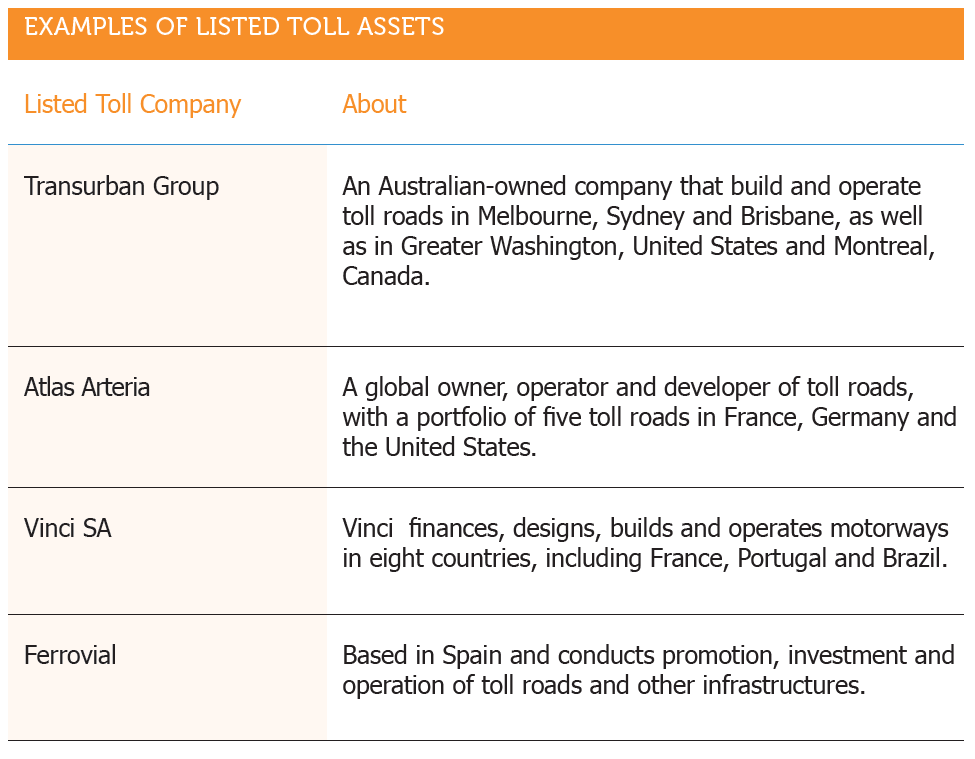

While we tend to think of toll roads as a recent phenomenon, they have been around for thousands of years. Toll roads today are a popular way for cash-strapped governments to raise money and improve the quality of, and reduce the congestion on road networks. Given the huge capital costs (toll roads often cost billions of dollars to build), for most investors the listed market is the only way to gain access to these assets. Types of toll roadsThere are two main types of toll roads; inter-urban toll roads (those between cities); and intra-urban toll roads (those within cities), which can be further be divided into radial, orbital and high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes. Each road varies in terms of its dynamics but, in general, this difference stems from the types of users and the trips undertaken. Intra-urban toll roads typically host a higher proportion of cars - with a significant part of this related to people traveling to and from work and going about their daily lives. Consequently, in an economic downturn, while some traffic will divert to the alternative free route, as long as people have jobs to go to or errands to run, the diversion is likely to be minimal. By contrast, roads between cities tend to have higher proportions of commercial traffic and discretionary trips, which are more economically sensitive.

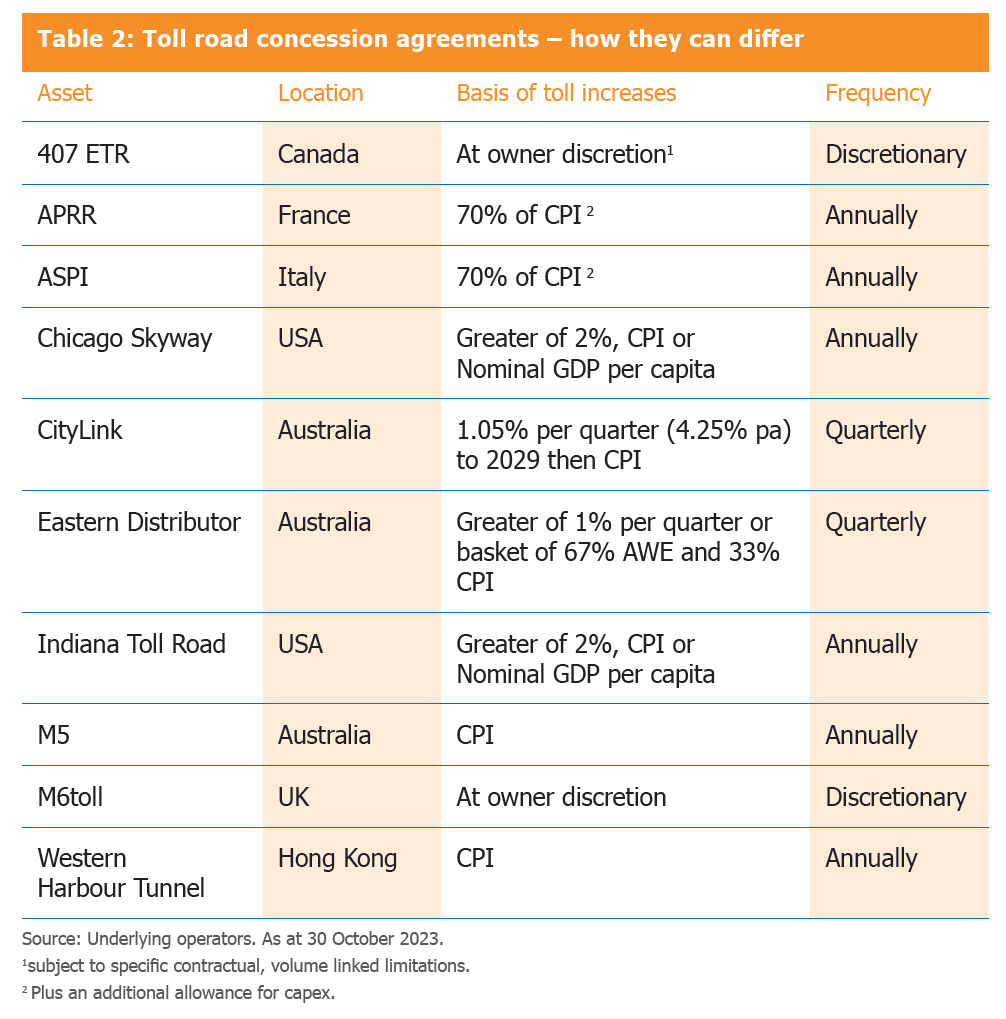

As is generally the case for transport infrastructure, the revenue for a toll road is a function of volume and price. In the case of toll roads, this can be put simply as: Toll road revenue = Traffic volume x toll price Pricing Mechanism for toll roads?The typical business model for a toll road is that a government agency enters into a concession agreement (contract) that entitles a toll-road operator to collect tolls for a defined period and increase those tolls on a regular basis in a defined way. The basis on which tolls are increased is controlled by the terms of the concession agreement and the level of tolls is generally linked to inflation. Table 2 shows how contracts differ. In Canada, the owner of the 407 ETR tollway can raise tolls with minimal constraints, while in Australia toll increases are linked to the consumer price index, the rate of inflation or 1 per cent per quarter. The pricing mechanism for these toll roads generally tracks increases in inflation with minimal lag. Consequently, most toll-road owners have the ability to respond quickly to any rise in inflation.

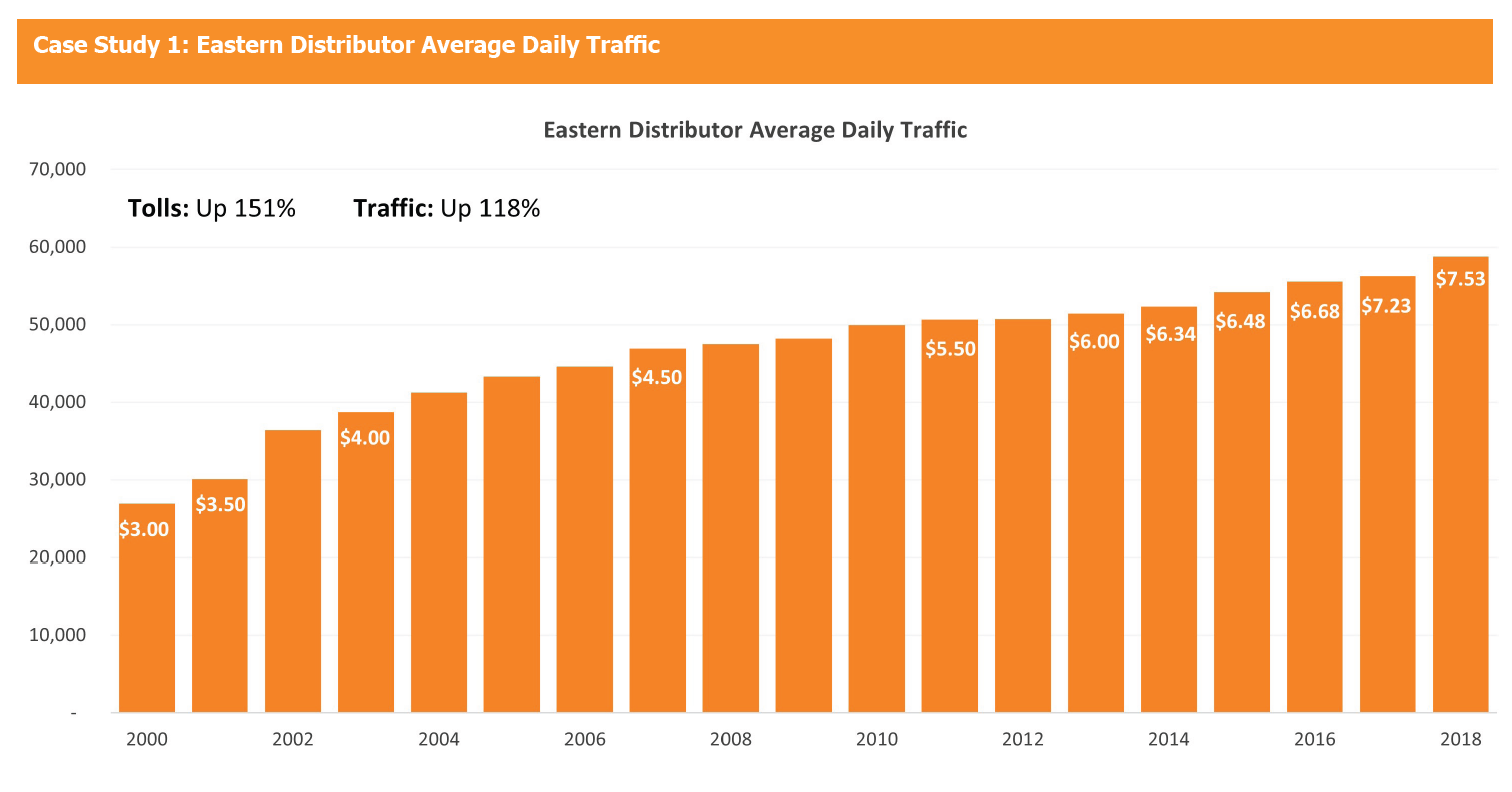

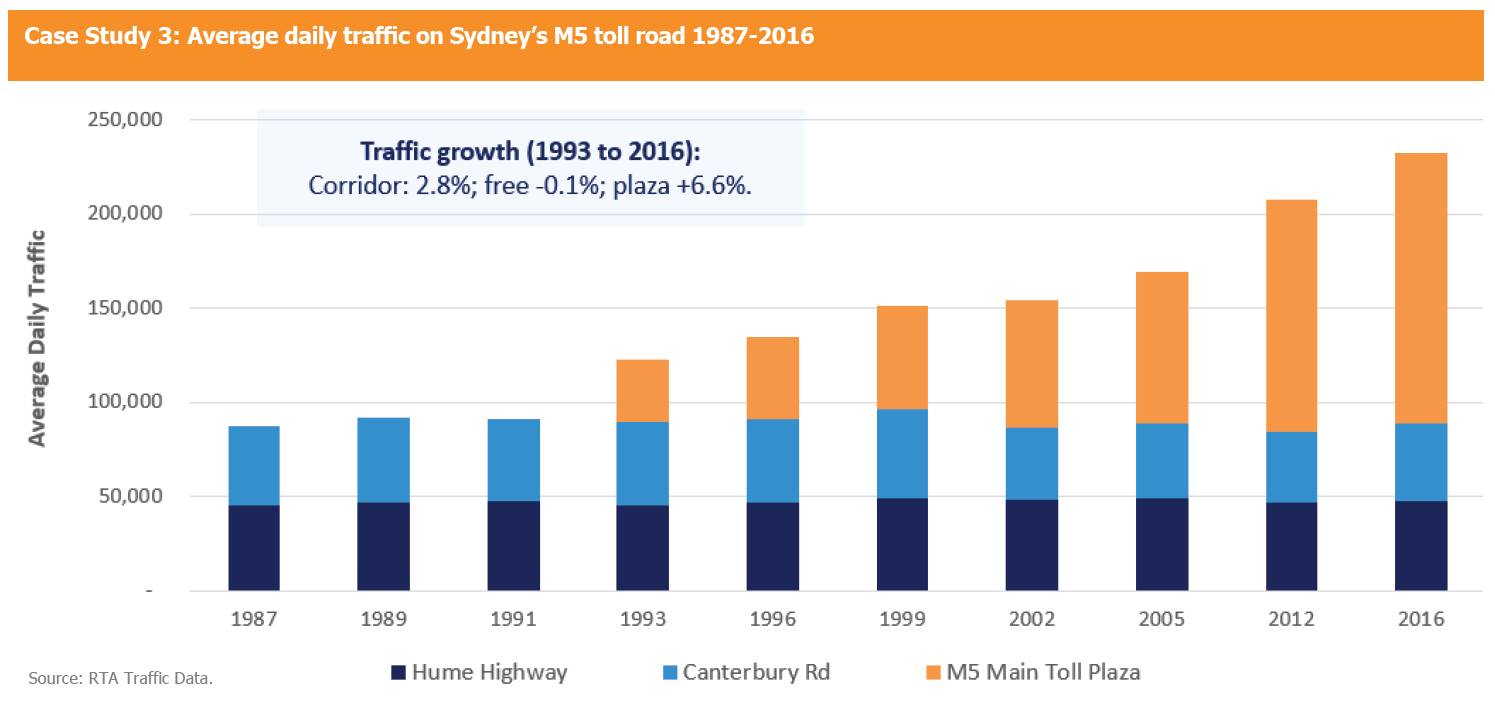

As tolls increase, there is generally a temporary switching effect where some users shift to the toll-free alternative. This causes competing routes to get more congested, which boosts the attractiveness of the tolled route. This results in an increase in total revenue, all things being equal, as the toll increase more than offsets the temporary decline in traffic. This can be seen from the below case study 1, that shows traffic on Sydney's Eastern Distributor, which grew 118% over 18 years despite tolls increasing 151% over the same period.

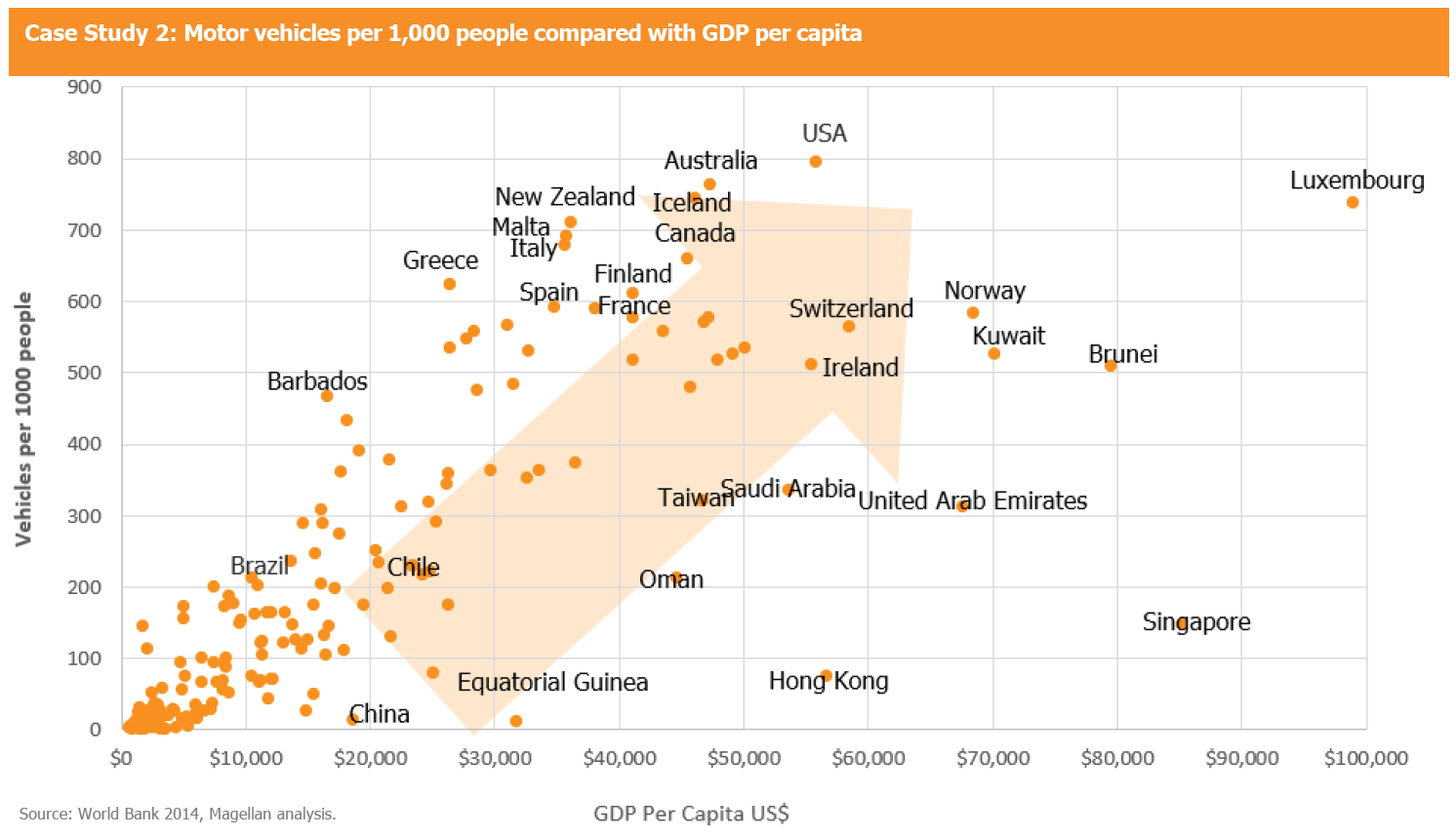

Three main factors affect the volume of traffic on toll roads. Case Study 2 below, shows the number of cars per thousand people in different countries around the world. It shows that as countries become wealthier, the demand for transport and mobility leads to increases in car ownership. The direct relationship between the demand for transport and economic development underpins the need for transport infrastructure.

1. Misalignment of incentives This is one of the reasons Magellan places so much emphasis on the governance or agency risk of these businesses. Incentives drive behaviour. A management team with incentives that align with the needs of long-term asset owners is less prone to such errors. 2. Congestion charges A congestion charge increases the cost of a trip into the charged area, which would be expected to shift people to other modes of transport; in particular, public transport. Other solutions such as Washington DC's dynamic pricing on parking meters may also reduce traffic at the margins. 3. Technological disruption Toll roads today typically can handle about 2,200 vehicles per lane per hour. A study by the University of California1 concluded that full penetration of self-driving cars could double this capacity. This is because computer-driven vehicles will be able to travel much closer together, at much higher speeds and in much thinner lanes. The long-term impact on toll roads will depend on the balance between additional trips created by driverless cars minus the additional capacity that is created on the free roads 4. Working from Home 5. Declining licence uptake among younger adults An Australian study into the same phenomenon2 suggested a range of explanations. Potential causes included increasingly restrictive access to learners and full licensing requirements along with lifestyle factors - increased tertiary education, staying at home longer and delaying working and having children, and the reduced status symbol of a car. The study found that young people who maintain frequent contact with friends through technology are more, not less, likely to see their friends in person. Toll roads can generate growing and inflation-protected income streams for long-term investors. While the risks are low compared with most equities, the risks of these assets are nonetheless real - particularly when they pertain to agency risk. In-depth research and a good understanding of the drivers of the business and incentives of management teams should allow investors to reap the benefits of these largely misunderstood assets. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 ('Magellan') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should obtain and consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement ('PDS') and Target Market Determination ('TMD') and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making a decision about whether to acquire, or continue to hold, the relevant financial product. A copy of the relevant PDS and TMD relating to a Magellan financial product may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any financial product or service, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to implement its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. No representation or warranty is made with respect to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information contained in this material. Magellan will not be responsible or liable for any losses arising from your use or reliance upon any part of the information contained in this material. Any third party trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and Magellan claims no ownership in, nor any affiliation with, such trademarks. Any third party trademarks that appear in this material are used for information purposes and only to identify the company names or brands of their respective owners. No affiliation, sponsorship or endorsement should be inferred from the use of these trademarks. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan. |

15 Jan 2024 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Rowe Price Global Equity (Hedged) Fund - I Class | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Rowe Price Dynamic Global Bond Fund S Class | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Rowe Price Dynamic Global Bond Fund I Class | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Perpetual Balanced Growth Fund | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Perpetual ESG Real Return Fund | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Perpetual Diversified Real Return Fund - Class Z | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 790 others |

21 Dec 2023 - What is the Fed's Senior Loan Officer Survey and what is it telling us?

|

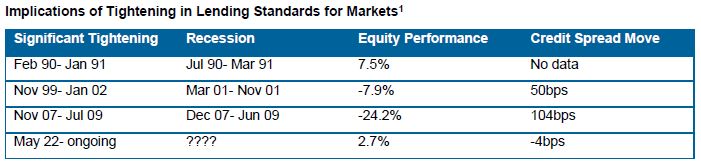

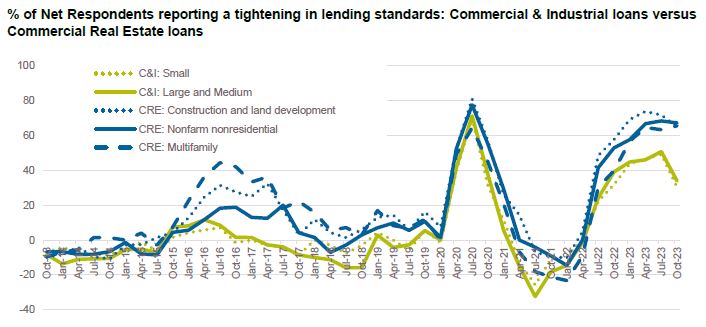

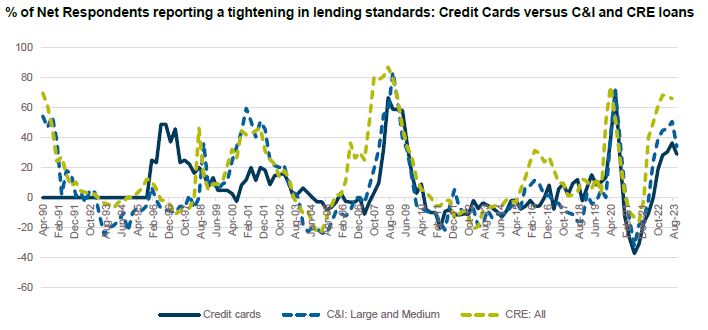

What is the Fed's Senior Loan Officer Survey and what is it telling us? Challenger Investment Management November 2023 The financial system of the United States is unique. Unlike Australia where households and institutions are at the mercy of the four major banks, the US banking system is highly dispersed. There are over 4,000 commercial banks and over 500 savings and loan associations. The top 4 banks represent less 50% of total assets in the banking system; in Australia this figure is over 70%. With so many individual lenders, the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed) conducts a quarterly survey to gauge the degree to which financial conditions are changing. This is called the SLOOS, the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. The survey polls up to 80 large domestic banks and 24 branches of individual banks. The questions address the degree to which banks are tightening lending standards, how the demand for credit is evolving as well as how the pricing of credit risk is changing. The results of the survey are reported to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and feed into monetary policy decision making. The survey has been repeatedly shown to have high predictive content with a tightening in lending standards being strongly correlated with a slowing in GDP growth. In this month's "What We're Watching" we take a closer look at the Senior Loan Officer Survey in an attempt to identify the degree to which standards are tightening and where the tightening is most acute. Observation 1: Previously when banks tightened by as much as they have done to date, a recession has followed A challenge in interpreting the survey data is that the questions asked of the banks have binary responses with the measure tracking the net percentage of respondents answering in the affirmative. It gives no indication as to the degree to which standards were tightened or pricing increased. There are also small biases in responses; for example, a bias towards tightening of credit standards with an average 6% of net respondents indicating tightening for C&I loans since 1990. Since 1990 there have been 4 periods of significant tightening in credit standards (which we define as 4 consecutive quarters where 20% or more of net respondents reporting tightening in standards for C&I loans). All 3 previous periods of significant tightening in credit standards were followed by a recession and in two of the 3 a selloff in credit and equity markets.

There have also been several periods where banks have meaningfully loosened credit standards. The mid 1990s (mid 93 to mid 95) and mid 2000s (early 04 to mid 06) saw extended periods of loosening lending standards. More recently banks loosened lending standards from early 2021 to mid 2022 including the most negative net percentage of respondents reporting tightening on record; -32.4% for the quarter ended Jul-21 (although it is arguable that some of this loosening was a reversal of the sharp tightening we saw when COVID hit). Our take is that the tightening in lending standards is not over. While standards were not excessively loose in 2022, we think the tightening will eventually weigh on risk markets. Observation 2: pricing on C&I loans is increasing The SLOOS also asks banks whether they are increasing spreads of loans over the Banks' cost of funds. Historically banks have had a slight bias towards tightening pricing albeit with responses being far more volatile than responses around lending standards. Interestingly the correlation between tightening in lending standards and changing spreads is only around 60%. Banks tend to reach a point where they are unwilling to loosen lending standards any further but are still willing to compete on price. For example, banks tightened pricing on C&I loans for longer periods than they loosened credit standards; from early 1993 to mid 1998 and from mid 2003 until mid 2007, respectively. In contrast, when standards tighten banks tend to also widen pricing concurrently. The widening in pricing has two effects - it further exacerbates credit pressure on borrowers, especially when combined with the significant increase in base interest rates. Secondly it creates opportunities for alternative lenders to disintermediate the banks. Observation 3: CRE lending standards are far tighter than C&I lending standards Commercial real estate (CRE) lending standards have tightened by far more than commercial and industrial loans. Demand for credit has also declined to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Even sectors such as Multifamily which are performing relatively well in a fundamental sense are experiencing a sharp tightening in lending standards.

To date, non-farm non-residential CRE lending has experienced 5 consecutive quarters where more than 50% of net respondents have tightened lending standards. The longest such period on record was the GFC with 7 quarters. No other period since 1990 has seen more than 2 consecutive quarters of >50% net respondents tightening credit standards. Observation 4: The consumer is still okay The survey data for credit cards implies a far less severe tightening in credit standards. The leadup is similar with the 2020 tightening and 2021 loosening in credit standards tracking closer to C&I and CRE loans but paths diverge in late 2022. New and used auto loans have experienced even less of a tightening in standards than credit cards.

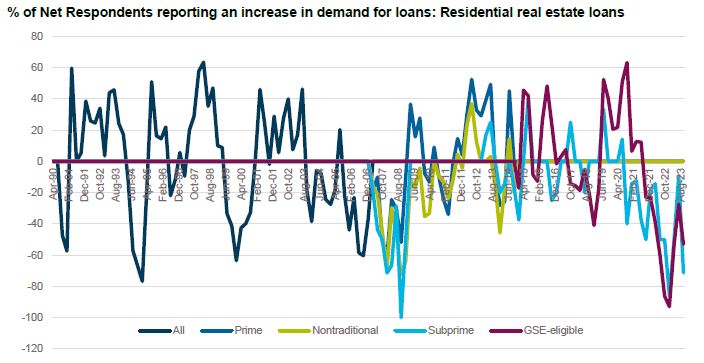

Residential mortgages, the epicentre of the GFC, have also not experienced a material amount of tightening in credit standards. Demand for consumer credit, both secured and unsecured has also not picked up materially with a reduction in demand being reported for auto loans and consumer loans ex credit cards and auto loans. However, demand for mortgages has fallen to GFC lows, in large part due to mortgage rates which are around 8%, levels not seen for more than 20 years.

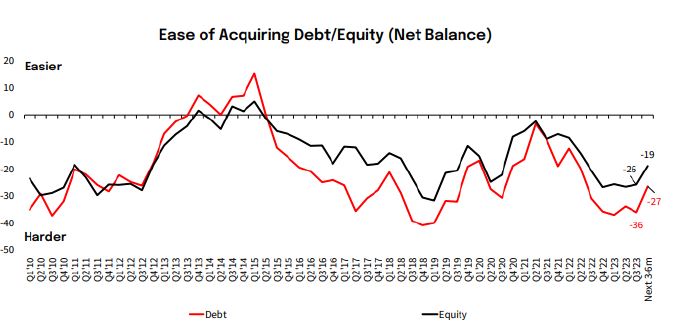

Domestic survey data While APRA does not collate consolidated survey data on lending conditions, several banks conduct their own surveys. NAB completes a quarterly survey on commercial property markets where borrowers have reporting difficulties in accessing credit with availability in line with pre-COVID levels. This suggests that while credit standards for real estate lending are tightening in Australia, they are not tightening at the same pace as in the United States.

In conclusion... Despite the relatively benign indications in Australia, the SLOOS implies a far sharper tightening in credit conditions especially in commercial real estate lending markets. Pricing of risk is also heading higher. While we don't necessarily expect tighter lending conditions in the US to flow directly to Australia (in aggregate our banks are in a stronger capital and liquidity position than the US banking system), we do think the tighter conditions in the US may precipitate an increase in risk premiums across markets. After all, when the US sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. Funds operated by this manager: Challenger IM Credit Income Fund, Challenger IM Multi-Sector Private Lending Fund For Adviser & Investors Only [1] All the data in this report is sourced from the SLOOS which is produced by the Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/data/sloos.htm |

20 Dec 2023 - Investment Perspectives: 12 surprising charts for your Christmas stocking

19 Dec 2023 - The 'low emissions' megatrend: Is it too early to invest in green hydrogen?

|

The 'low emissions' megatrend: Is it too early to invest in green hydrogen? Insync Fund Managers December 2023 The 'low emissions' megatrend is decarbonising business models, driving long term value for investors and helping corporates and countries attain climate related goals. Insync Funds Management CIO, Monik Kotecha said, 'The main levers of the low emissions megatrend are cost competitive renewables that have experienced massive drops in their establishment, then production costs, compared to their fossil fuel and nuclear peers.' This, he said, is what is driving the 'electrification of everything' including transportation, heating, industrial operations, etc. 'More than just clean energy generation, it also encompasses digitally optimised energy efficiency systems, decentralised energy generation and overhauling entire electricity grids.' Half of the world's demand for energy is projected to be served by 'clean molecule' sources by 2050 and hydrogen, the first, lightest and most abundant element in the universe, is set to play a vital role. 'Electrification alone won't get us to net zero,' Mr Kotecha said. 'Hydrogen as part of an energy mix could supply sectors not suited to electricity, such as heavy machinery and heavy industries, in lieu of fossil fuels.' Seen as a potentially environment-friendly transformative force Mr Kotecha said hydrogen is an enticing prospect for investors, green hydrogen in particular. 'However, it is vital to temper enthusiasm with a dose of realism, given the hurdles on the path to profitability.' At the heart of the challenge, he said, lies competition with fossil fuels. 'Currently, they are more cost-effective and often heavily subsidised by governments, which means green hydrogen is dependent on external private financial support. Subsidised carbon economics continues to dominate over environmental concerns, and this will remain a challenge until subsidies, scale, infrastructure, and technology advances for green hydrogen level up the current 'unlevel' playing field.' Most hydrogen today is produced by extracting it from oil, coal or natural gas. In order to justify substantial capital investment for an environment-friendly production source, high-capacity utilisation is essential. 'Green hydrogen is made by splitting the water molecule via electrolysis to create hydrogen. This demands a stable green power source, which is no small feat - although this complex issue is rapidly being overcome.' A variation to green hydrogen is pink hydrogen (electrolysis powered from nuclear energy). New salt based nuclear reactors already under construction could proffer a cost effective and far safer and environmentally friendly power source than today's typical fission reactors, thus meeting the need for stability of supply. However, it is likely that the green hydrogen sector will require a more extended investment horizon to realise its full potential or until new technology breakthroughs like those encountered in solar impact the economics. 'In other words, unfortunately, we don't think green hydrogen has yet reached an essential economic tipping point to be a profitable component of the low emissions megatrend, nor produce companies that meet our high profitability criteria, but we will continue to watch and see.' Funds operated by this manager: Insync Global Capital Aware Fund, Insync Global Quality Equity Fund Disclaimer |

18 Dec 2023 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Firetrail S3 Global Opportunities Fund (Hedged) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Firetrail Australian Small Companies Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Firetrail S3 Global Opportunities Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| India 2030 Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| UBS Emerging Markets Equity Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| OAM Select Income Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 750 others |

18 Dec 2023 - Glenmore Asset Management - Market Commentary

|

Market Commentary - November Glenmore Asset Management December 2023 Globally equity markets recovered strongly in November. In the US, the S&P 500 rose +8.9%, the Nasdaq increased 10.7%, whilst in the UK, the FTSE 100 was more muted, rising +1.8%. The key driver of the rally was data points showing cooling inflation, which in turn saw bond yields fall materially. The US 10-year bond rate declined -58 basis points to close at 4.26%. Its Australian counterpart fell +52bp to close at 4.41%. The weaker inflation data provided hope that the restrictive interest rate hikes of the last 18 months may be nearing an end. In Australia, the All-Ordinaries Accumulation Index rose +5.2% in November. Top performing sectors were healthcare and real estate (a clear beneficiary of lower bond rates), whilst energy was the worst performing sector, driven by a fall in oil and gas prices. Positively for the fund, small cap stocks outperformed large caps as investor risk appetite improved with falling bond rates. Given the material underperformance of small cap stocks vs large caps in the last 18 months, we believe the next few years should be positive for the fund given its skew to small caps, where we are seeing quality companies across numerous sectors priced very attractively. Funds operated by this manager: |