NEWS

26 Apr 2022 - Hedging against inflation - gold or real estate?

25 Apr 2022 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Microequities Value Income Fund | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Salt NZ Dividend Appreciation Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Salt Sustainable Global Shares Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Salt Sustainable Income Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Morgan Stanley Global Sustain Fund | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 650 others |

22 Apr 2022 - Airlie Insight: The dominant narrative of 2022 for stocks

|

Airlie Insight: The dominant narrative of 2022 for stocks Airlie Funds Management April 2022

|

|

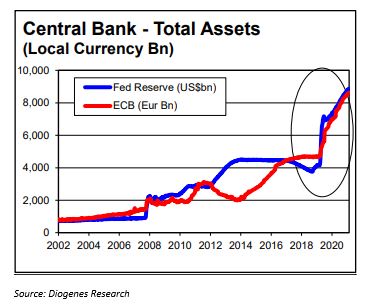

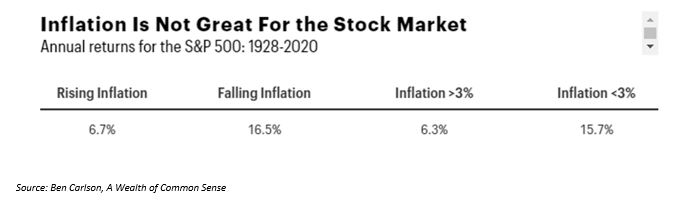

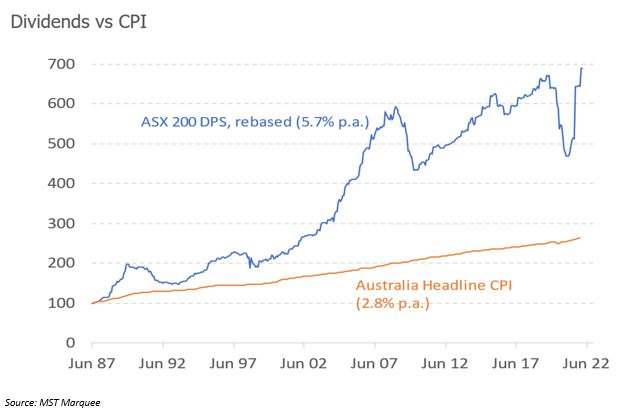

Last quarter we talked about the danger of following blindly (and reacting to) the 'dominant narrative' that is prevalent at any time in the market. However, there is no denying we are at the crossroads where inflation plus central bank tapering equals higher interest rates. Nothing encapsulates the excesses of the past decade better than the chart below showing central bank asset growth (i.e., buying assets/money printing). It seems unlikely that the similarity in the growth of global equity markets over this period is a coincidence. Is this inflation spike transitory or structural? Some of it is clearly transitory driven by covid-19-affected supply chain issues; however, add in the energy and commodity price shock from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and suddenly 2022 looks different from most of the past decade. The 'dominant narrative' is all-encompassing, and the first impact is an increase in volatility in equity markets. In 2021, the S&P 500 Index had the fewest market drops (or 'drawdowns' in the professional lexicon) in recent history. It seems reasonable that the uncertainty of just how high rates will go will lead to a lot more volatility, and this has certainly been the case thus far in fiscal 2022. From recent peaks, the NASDAQ and S&P 500 fell 22% and 13% respectively but have now rallied 13% and 9%. The S&P/ASX 200 has done even better - falling 10% from the January high only to rally 10%, leaving it only 1% from the all-time high set in August 2021. The Australian market has been bolstered by its high weighting to banks and energy and resource companies. Many pundits are calling this sudden snap-back rally a 'dead cat bounce' due to perhaps a view that the Russian-Ukrainian situation evolves into some sort of truce hopefully soon. At that time the 'dominant narrative' will then return and take charge leading to slowing economic growth and possibly recessions. The chart below shows that it's certainly been the case that markets do not do as well when inflation is both rising and is above 3%. This is the exact opposite situation of the past decade where we've had falling inflation and below 3%. Not shown on the chart is that markets produce negative returns when inflation persistently exceeds 6%. So, what does it all mean and what to do? Unfortunately, it's impossible to answer. We've met investors this year who have proudly told us they've gone to cash as the market hit the 10% drawdown because the 'dominant narrative' is obvious - equity markets will fall, economies will falter. They may ultimately be right, but I've wondered what they make of the rally back to within 1% of all-time highs? The performance of non-profitable tech, the return of so-called value stocks, and the valuation implication of higher rates lead us to think that the one-way trip of the market over the past decade and the return of volatility may mean stock-picking comes to the fore and there are increasing opportunities for active managers to differentiate themselves. Also not forgetting the fact that the equity market is the best place to counter inflation. The chart below shows that just the dividends alone from listed Australian equities have preserved investors' buying power over the long term. With all the doom and gloom and headline fodder provided by the above debates it's easy to forget that the Australian economy remains in good shape. The strength is widely spread across the economy: from households enjoying strong employment prospects with wage rises, increasing house prices, falling mortgage repayments (for now), to miners reaping solid commodity prices, farmers rebounding from the drought, and banks experiencing renewed credit growth. So where to from here? The case for further strength in equity markets is a relative one. Absolute valuations are high relative to history and are vulnerable overall to higher interest (discount) rates. The energy shock brought about by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and higher commodity prices generally are supportive in the short term to our resources-heavy market. Also, as the chart below shows; equally supportive is the forecast dividend yield available from the ASX 200 - a healthy dividend return of 4.0% - making it the equal-highest-yielding equity market in the world. Calendar year 2021 was a year of significant capital return for investors, as many ASX companies were carrying surplus capital: banks, miners, retailers, and many industrials had seen dramatic balance sheet improvements over the past 18 months. We expect continuing healthy capital returns to shareholders, notwithstanding the global uncertainty. By Matt Williams, Portfolio Manager Funds operated by this manager: Important Information: Units in the fund(s) referred to herein are issued by Magellan Asset Management Limited (ABN 31 120 593 946, AFS Licence No. 304 301) trading as Airlie Funds Management ('Airlie') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should obtain and consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement ('PDS') and Target Market Determination ('TMD') and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making a decision to acquire, or continue to hold, the relevant financial product. A copy of the relevant PDS and TMD relating to an Airlie financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4760 or by visiting www.airliefundsmanagement.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any financial product or service, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to implement its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of an Airlie financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Airlie makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Airlie. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any third party trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and Airlie claims no ownership in, nor any affiliation with, such trademarks. Any third party trademarks that appear in this material are used for information purposes and only to identify the company names or brands of their respective owners. No affiliation, sponsorship or endorsement should be inferred from the use of these trademarks.. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Airlie. |

21 Apr 2022 - Redwheel: How the green wave is influencing emerging markets

|

Redwheel: How the green wave is influencing emerging markets Channel Capital April 2022 For professional investors and advisers only The road to net zero emissions has the potential to set in place the conditions for a commodity super-cycle which has significant implications for emerging and frontier markets. Governments and authorities made many pledges following the two-week COP26 meeting in November 2021. More than 100 countries, including Brazil and Russia, agreed to end deforestation by 2030. Another 80, led by the US and the EU, pledged to cut methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030 while over 40 countries made new commitments to phase out coal power despite China, US, India and Australia holding back. These widespread commitments to achieve carbon neutrality are likely to intensify electrification and renewable energy efforts, creating multi-decade support for relevant industries. Solar is set to play a more important role while producers of "green wave" materials like copper, uranium and lithium may also be key beneficiaries of this trend. INVESTING IN CLIMATE CHANGE An estimated $56tn in incremental infrastructure investment should be needed to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050. This implies an average annual investment of $1.9tn in decarbonization worldwide. If politicians commit a fraction of the capital which they have talked about we believe that copper, aluminium, nickel, cobalt and lithium prices could increase significantly as supply and demand dynamics may create serious bottlenecks. The majority of these commodities is located in emerging markets. The economies which are net exporters of these metals should be beneficiaries of higher prices as the contribution of exports to GDP increases rapidly.

We see equity outperformance from companies that produce commodities related to the electrification of the global economy and businesses involved in the respective supply chains (e.g. copper/lithium, electricity transmission, energy storage). The Redwheel Emerging and Frontier Markets team has identified several key themes that look set to benefit from this long-term secular growth opportunity: Sustainable Energy, New Auto Tech and Copper. SUSTAINABLE ENERGY The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that global electricity demand could double by 2050 under a net zero scenario.¹ We believe that demand has the potential to grow more than that. As the world continues to focus on decarbonization, the majority of the new sources of electricity will have to be generated sustainably. We identify and invest in companies that are actively involved at any point in the supply chain of low carbon energy. The target of sustainable energy is to produce affordable and reliable energy for extended periods of time, while at the same time helping to combat climate change with the lowest possible emission of CO2 and other greenhouse or polluting gases. We have key portfolio holdings across different sectors such as solar power and nuclear energy. SOLAR POWER The development of solar power will be crucial in phasing out fossil fuels. Solar PV² is becoming the lowest-cost option for electricity generation in most of the world leading to significant investment in the coming years and strong growth for solar power manufacturers. In the solar sector, after years of expansion and consolidation, Chinese suppliers now represent more than 80% of the effective capacity in most segments across the solar supply chain.³ Chinese solar suppliers started to expand their capacity in 2019 on the back of stronger visibility on future demand. The robust performance of these companies in the equity market has enabled them to raise capital and further accelerate their expansion plans.

LONGi is the largest mono-silicon wafer producer in the world and is set to be a key enabler of the shift to solar power. We expect ongoing vertical integration (from wafer to cell and module) to potentially further boost LONGi's market share in the global module markets. Additionally, LONGi believes the distributed solar market in China, especially commercial and industrial, should see strong demand in 2022 driven by government policies. In 2021, distributed solar modules accounted for 15-20% of LONGi's total module shipment, which may increase to 35-40% in 2022. LONGi believes the distributed solar market has higher module price affordability than solar farms, leading to higher margins. URANIUM Nuclear energy has been brought back into the spotlight due to its low cost and high energy efficiency. Nuclear capacity is increasing in countries such as China and India due to the constant search for more sustainable forms of energy. This is offsetting the decommissioning and decline of nuclear as a source of electricity generation in Western countries. However, we believe that nuclear power will regain political support in the US and parts of Europe which will drive life extensions of existing reactors and positively impact medium term demand. Additionally, supply curtailments by key industry players such as Cameco and Kazatomprom could continue to drive uranium prices higher, benefitting low cost uranium miners.

Kazatomprom is the world's largest uranium producer commanding a direct share of 45% of the world's production. Its mines operating in Kazakhstan are also the lowest cost uranium producer globally. This uranium miner will be a key beneficiary from the expected rise in uranium prices.⁴

COPPER We have been bullish on the role of copper in the drive for global decarbonization for several years. Copper is one of the key metals and beneficiaries of the electrification of the global economy, whether through the production of electric vehicles or the electrification of industries and is crucial in the construction and build out of renewable energy. For example, electric vehicles use seven times more copper per car than vehicles powered by internal combustion engines while wind power is five times as copper intensive as thermal power stations. A wholesale switch would require the copper supply to almost double from today's levels.⁵ On the supply side, large existing copper producers are struggling to maintain copper production at current levels as higher cost underground mines are replacing above ground open pit mines. Ore grades have decreased substantially, and our research suggests new copper greenfield projects are only viable at sustainable prices of over $3.50 per pound of copper. These supply issues, combined with secular growth in demand, suggests that the outlook for the base metal is positive over the coming years. Emerging markets account for over 60% of the copper supply globally, therefore we see several emerging markets benefitting from the robust long-term supply-demand dynamics of copper.

In Zambia, First Quantum Minerals operates one of the largest copper mines globally. The company is set to benefit from an appreciation in the copper price over the next decade due to robust demand and subdued supply.

NEW AUTO TECHNOLOGY There is currently a dramatic change taking place in the world's transportation sector. New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) are replacing vehicles with internal combustion engines (ICEs). NEVs require different materials for construction and operation which lead to a new set of beneficiaries within the automobile supply chain. We believe there is a considerable growth opportunity within the upstream segment of the NEV value chain. Demand for commodities such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper and platinum group metals should rise exponentially as the penetration of NEVs increases worldwide. The supply dynamics of many of these commodities are strained which will likely lead to higher and more stable prices over the medium to long term. Electric vehicles are the main driver of future lithium demand, accounting for c30% of total lithium demand currently and potentially rising to over 60% by 2025e⁶. As a result, lithium demand is expected to grow 20-25% annually in the medium term. We expect lithium prices to be supported over the next decade by strong demand and lagging supply leading to deficits. SQM operates one of the world largest lithium mines in Chile and is well positioned to take advantage of this price environment. The company should see robust production growth through the end of the decade, while its projects have attractive positions on the cost curve. Additionally, SQM has a solid balance sheet to fund this growth and has significant leverage to lithium prices.

WHAT HAPPENS TO FOSSIL FUELS? The global economy will remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels for several decades to come despite the transition to a green economy. Even if all the currently announced climate pledges were fully implemented, oil demand in 2050 would still be 75m barrels per day, down only 25% from current levels (source: IEA, 13/10/2021). However, capex in the sector is down 50% from its peak in 2014. Thus, it is quite possible that the supply of fossil fuels will decline more than demand as the development of low carbon alternatives may not be adequate to keep the market balanced. Underinvestment in the hydrocarbons sector amid green transition efforts and changing government regulations could lead to growing energy scarcity.

This structural underinvestment in high carbon sectors is likely to drive hydrocarbon prices higher over the medium-to-longer term, raising affordability concerns, but also increasing the innovation of decarbonization technologies. CONCLUSION In conclusion, as the momentum behind the 'E' of ESG grows stronger, we will continue to see an increasing demand for greener materials and we believe Emerging Markets are set to benefit. However, unless more investment comes through, mined raw materials may become a bottleneck to tackling climate change. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: CC Redwheel Global Emerging Markets FundSources

Important Information No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. |

20 Apr 2022 - Looming French presidential election

|

Looming French presidential election 4D Infrastructure April 2022 The French presidential election is underway, with a first-round vote on Sunday 10 April and the run-off between the top two candidates on Sunday 24 April.

In a likely replay of 2017, the polls suggest incumbent President Emmanuel Macron will face far-right candidate Marine Le Pen in the run-off. In this piece we consider some of the key issues at play and the implications for us as infrastructure investors. Meet the candidatesFrom far-left to far-right, there are 12 official candidates for the election. As of 2 April, opinion polls are placing Emmanuel Macron ahead with 24% to 33% of vote intentions, with the other candidates fighting for the runner-up position. Key policy positionsThe table below summarises the key policy positions of the four leading candidates and how they may impact the current and potential future infrastructure investment environment. Impact on infrastructure investmentIn terms of sector specifics, energy/climate policies have dominated the campaign with all candidates expressing a view - albeit quite different ones - around need, support, funding and timing of the energy transition. These policies represent potential head and tail winds for the infrastructure sub-sectors exposed, but overall it means significant investment in the sector, potentially creating many future private sector investment opportunities. Outside the energy space, the argument of private versus public ownership of the transport sector has again come into play and could have ramifications for those stocks exposed, such as Vinci, Atlantia and ADP. A second Macron termA Macron win would not alter the fundamental outlook for the infrastructure sector relative to today. However, it will cement a positive infrastructure investment cycle with more than €10bn of investment towards energy transition and Russian gas independence. The pace to renewable energy as base load power could also accelerate and benefit renewable operators such as Neoen, Voltalia, Orsted. We would expect further integration with Europe in terms of security of energy supply benefiting the integrated players. We have also seen a shift in thinking around nuclear. We expect Macron, in a second term, to revive what had been an out-of-favour sector with important investment packages to both extend the life of existing plants and develop new generation reactors (to the benefit of Engie, EDF or Vinci). Outside the energy sector, we believe the current motorway network concessions could be extended in exchange for capital expenditure commitments, supporting improved motorway efficiency and growth profiles of the key players such as Vinci or Atlantia. A Le Pen winLe Pen has dropped her controversial proposal to exit the euro, which we believe reduces the risk to the overall French economy relative to 2017. Due to the extreme nature of her economic positions, a Le Pen victory would lead to clear winners and losers in the infrastructure space. The biggest threat from a Le Pen victory would be the nationalisation of assets of listed entities with toll roads and airports clear targets, which would be detrimental to domestic listed players such as ADP and Vinci as well as foreign players with exposure to French infrastructure. Regardless of whether nationalisation is a serious threat (legally or otherwise), it would be a clear overhang for the sector - much like a potential Jeremy Corbyn victory was for the UK in 2019. Even without nationalisation, in a Le Pen victory the infrastructure sector will likely experience stricter sector regulation (as far as it is possible within the concession construct). Positively, Le Pen has expressed a willingness to pursue the energy transition. However, certain sectors are definitely not in favour (wind), and she would push for limitation of the EU influence on French energy policy. ConclusionWe are expecting a Macron/Le Pen run off with Macron ultimately re-elected for a second term. However, unless Macron can also win a majority in the parliament, we could see a fragmented legislature with increased difficulty in policy execution stalling reforms. Regardless of who wins, we see continued positive momentum in energy transition and investment as all parties work towards this common goal, and more of a status quo for the transport names with existing earnings underpinned by long-term concessions. Should Le Pen win, we would revisit our transport exposure in the near term. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: 4D Global Infrastructure Fund, 4D Emerging Markets Infrastructure FundThe content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. This commentary in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader. |

20 Apr 2022 - The Ardea Alternative - Foreign Currency Management

|

The Ardea Alternative - Foreign Currency Management Ardea Investment Management 28 March 2022 Key Portfolio Construction Trade-Offs Dr. Laura Ryan and Tamar Hamlyn are joined by Dr. Nigel Wilkin-Smith to discuss the importance of currency management for AUD investors, along with the backdrop created by the regulatory environment in superannuation, particularly the YFYS performance test. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Ardea Australian Inflation Linked Bond Fund, Ardea Real Outcome Fund |

19 Apr 2022 - Two lessons on what to avoid in a market bubble

|

Two lessons on what to avoid in a market bubble Nikko Asset Management March 2022 Have you ever stopped to imagine what would happen if the world's central banks spent just over a decade pouring USD 25 trillion of liquidity into the economy, with more than 60% of that liquidity created in the last two years? If you are like the overwhelming majority of people, the answer is almost certainly no. The good news is you don't have to imagine as this is precisely the situation we are in today. In this article, we assess what has happened and provide some thoughts around how investors should navigate the next phase of the greatest financial experiment of all time.

USD 25 trillion is almost an unimaginable amount of money so what has happened to all of this liquidity? Well, rather inevitably, a lot of it has found its way into asset markets. The value of almost everything has gone up - considerably. From wine to whisky, growth stocks to digital gold, the returns to asset owners have been extraordinary since the depths of the financial crisis in 2009. Younger generations have gone from occupying Wall Street to trading Bitcoin on margin and buying meme stocks on trading platforms as if it were a video game. Old people "just don't get it" and lack the imagination to see just how enormous the returns will be. Make no mistake, there are many aspects of this that have the trappings of a bubble. This is nothing new. In late 1636 in the Netherlands, the Viceroy tulip bulb sold for four fat oxen, eight pigs or 12 fat sheep. As many bulbs flowered in 1637, prices crashed and by early 1638, the government decreed that tulip contracts should be annulled in return for the payment of 3.5% of the original price. There are many examples of financial speculation littered throughout history and interestingly several of these are also linked to technological innovation. Investors in railway bonds in the 19th century enabled the construction of vast networks in Europe and the US which enhanced productivity and had a huge impact on the way people lived and worked. Investors in railroads typically made little profit however, and most of the long-term gains were arguably made by the businesses and people in cities which grew up as a result of their newly connected status. The dot-com internet bubble of the late 1990s had a very similar story at its heart. Investors in the companies who built the internet networks and operated them thereafter either lost everything or made very poor long-term returns. The real beneficiaries of the networks created in the bubble were businesses like Apple, Google, Facebook, Netflix, and Amazon*, who used those networks to sell us the products and services that meant we got the most out of them. They were effectively the hotel at the end of the railway line which stood to gain the most from the passengers arriving on the newly constructed network. Is there a bubble today and if so, where is it and how can we expect things to pan out from here? The first thing that strikes us is investors' have very long-time horizons and the second is the sheer number of companies that are forecast to make significant losses for the foreseeable future. This is dangerous. The future is highly unpredictable, and far more things can happen than actually will happen. For example, if you were asked in 1969 what would be the greatest innovation in 40 years' time, you'd be forgiven for answering that humans would have colonised space and we would all be going on holiday to Mars (given Neil Armstrong had just set foot on the moon). Instead, the reality in 2009 was that the Apple iPhone was being rolled out which effectively placed the sum of all human knowledge in your pocket. We should be wary of people selling us a version of the future based on science fiction rather than practical and applicable facts.

Given the dangerous nature of these speculative businesses experiencing heavy losses and cash burn, what should we do from here? For us, understanding the drivers of cash flows and the returns on investment made by the companies we invest in is critical to the long-term health of our portfolio. By investing in businesses with strong competitive advantages who remain disciplined around capital allocation, we aim to find the next set of 'hotels at the end of the railway line' that will benefit from the new activities created by this latest bout of speculative excess. If lesson one is to avoid loss-making, cash-burning businesses chasing a pipe dream of market share, what next? In our opinion, lesson two is "beware the wolf of cyclicality wrapped up in the sheep's clothing of growth". The journey from a growth stock to a value stock can be damaging to your financial health. It strikes us that in industries such as digital advertising, investors may be mistaking a maturing industry that has seen a pull- forward of demand for one which still offers enormous secular growth. The pandemic saw an enormous amount of liquidity added to the system, and many speculative businesses received funding and/or very high valuations which they may not have otherwise. It's worth noting that a number of these new companies' costs (after generous option packages for senior staff) are spent on IT infrastructure and services, as well as digital advertising to gain market share. When you add in the pull forward of time spent at home/online for consumers in the pandemic, and inflationary pressures, it is perhaps no surprise that digital advertising in all its forms may face a more challenging outlook over the next few years. Navigating choppy watersIf we have established a few things to avoid, the obvious question remains around where are the opportunities? In our opinion, there are many businesses that have been left behind from the speculative excess of the last two years because their businesses have been negatively impacted by the pandemic which offer opportunities. In the provision of home nursing care and patient rehabilitation for example, companies such as LHC group and Encompass Health have suffered from dramatically rising costs due to a shortage of nurses exacerbated by the need for staff to quarantine following exposure to COVID-19. As the pandemic ebbs, the staffing situation is expected to normalise, and we see these companies benefitting from improving pricing as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a US federal agency that administers the Medicare programme, has affirmed reimbursement rates which begin to take account of these near-term challenges. This should position these companies for a better 2022 while many in the digital advertising industry may face exactly the opposite scenario. Another area we feel remains underappreciated is in the provision of contract catering. Punished by stringent lockdowns and a shift away from office-based working, many of these businesses were forced to raise capital and adapt quickly to a very new reality in the pandemic. As healthcare providers, schools and universities grapple with rising costs and labour shortages, they are now outsourcing their catering operations at a record pace and the pipeline of new business for a company like Compass has never been better. Also, consumption at stadiums where the firm has many concessions is booming as people make the most of attending live sports and cultural events. These businesses are reinvesting for structural growth, but many investors perceive them to be too old hat to be interesting. 'Boring' improvements in return on capital might be just the menu item investors should choose in what may continue to be a challenging 2022. Valuation rationality and margin for safetyWe have highlighted that we have been experiencing some speculative excesses within parts of the equity markets for some time, and there have been some clear parallels to historical bubbles. Our philosophy is focused on compounding clients' capital over time rather than being a slave to the shorter-term gyrations of the market. We focus on the following:

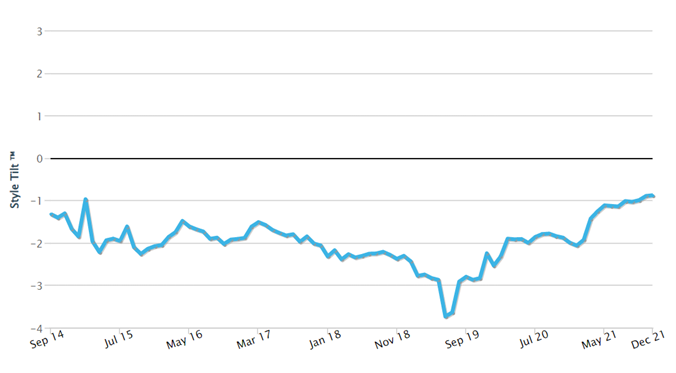

The latter point has been more relevant for portfolios in the last 12-18 months, as we have been in a period where easy monetary policy has encouraged investors to price future growth very generously. This has resulted in reductions in some holdings or a complete exit on valuation grounds, with the proceeds recycled into Future Quality companies that have better valuation support. We are comfortable paying a premium for companies that deliver better and more consistent growth, can attain, and sustain high returns on invested capital and have strong balance sheets - but that premium needs to be appropriate and fair. The following history from style analytics confirms that we have stuck to that discipline. Chart 1: Cash Flow Yield

Source: Style Analytics as at 31 December 2021

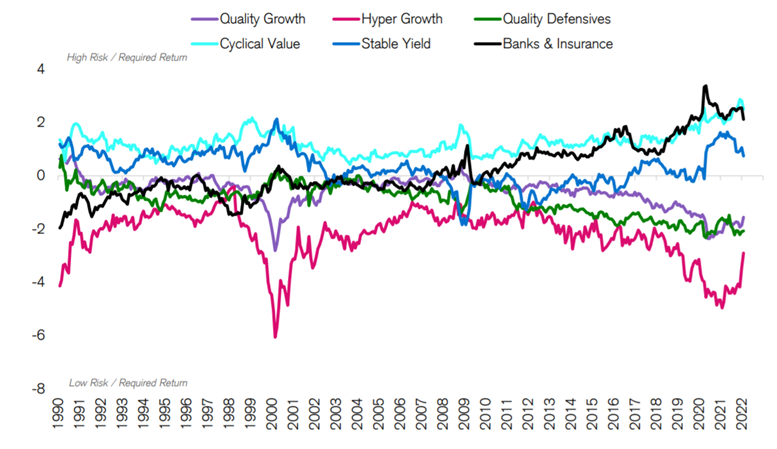

We believe we have entered an unknown period of tightening liquidity, with the evolution of supply-related inflationary inputs and central bank responses remaining the dominant drivers for returns from and within equities as an asset class. History would suggest that following an unwind from periods of excess, the prior winners typically don't regain leadership again. Given the lack of profitability of many companies that some have described as 'concept finance', this makes sense, as over the long term the delivery of cash flow and growth is the key determinant on share prices. Chart 2: Group Median Market Implied Yield (MIY) Spread vs Market

Source: Credit Suisse HOLT, Data date 2/4/2022. Universe: Top 2000 Global companies by TTM Market cap. Market Implied Yields for Financial firms on the HOLT CFROE model are trimmed by 150 bps throughout this analysis to preserve comparability.Chart 2 highlights that the growth versus value debate dominating many conversations is becoming less important for most companies. except for those with very high growth expectations. The path of future growth and profitability will likely soon start to dominate again as the driver for individual share prices once the current period of unwinding and rotation has exhausted. We believe our portfolio of Future Quality stock picks should be well placed when that time arrives. *Reference to individual stocks is for illustration purpose only and does not guarantee their continued inclusion in the strategy's portfolio, nor constitute a recommendation to buy or sell.Author: Iain Fulton (Portfolio Manager) and Will Low (Head of Global Equities), Nikko AM, Yarra Capital Management's global partner Funds operated by this manager: Nikko AM ARK Global Disruptive Innovation Fund, Nikko AM Global Share Fund, Nikko AM New Asia Fund, Disclaimer This material has been prepared by Nikko Asset Management Europe Ltd (NAM Europe) which is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the FCA. This material is issued in Australia by Yara Capital Management Limited (formerly Nikko AM Limited) ABN 99 003 376 252, AFSL 237563. To the extent that any statement in this material constitutes general advice under Australian law, the advice is provided by Yarra Capital Management Limited. NAM Europe does not hold an AFS Licence. Effective 12 April 2021, Yarra Capital Management Limited became part of the Yarra Capital Management Group. The information contained in this material is of a general nature only and does not constitute personal advice, nor does it constitute an offer of any financial product. It is for the use of researchers, licensed financial advisers and their authorised representatives, and does not take into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of any individual. For this reason, you should, before acting on this material, consider the appropriateness of the material, having regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs. The information in this material has been prepared from what is considered to be reliable information, but the accuracy and integrity of the information is not guaranteed. Figures, charts, opinions and other data, including statistics, in this material are current as at the date of publication, unless stated otherwise. The graphs and figures contained in this material include either past or backdated data and make no promise of future investment returns. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. Any economic or market forecasts are not guaranteed. Any references to particular securities or sectors are for illustrative purposes only and are as at the date of publication of this material. This is not a recommendation in relation to any named securities or sectors and no warranty or guarantee is provided. Portfolio holdings may not be representative of current or future investments. The securities discussed may not represent all of the portfolio's holdings and may represent only a small percentage of the strategy's portfolio holdings. Future portfolio holdings may not be profitable. Any mention of an investment decision is intended only to illustrate our investment approach or strategy and is not indicative of the performance of our strategy as a whole. Any such illustration is not necessarily representative of other investment decisions. Portfolio holdings may change by the time you receive this. Any reference to a specific company or security does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell, hold, or directly invest in the company or its securities. The information set out has been prepared in good faith and while Yarra Capital Management Limited and its related bodies corporate (together, the "Yarra Capital Management Group") reasonably believe the information and opinions to be current, accurate, or reasonably held at the time of publication, to the maximum extent permitted by law, the Yarra Capital Management Group: (a) makes no warranty as to the content's accuracy or reliability; and (b) accepts no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage arising from any errors, omissions, or information that is not up to date. Yarra Capital Management. Copyright 2022. |

14 Apr 2022 - Megatrend in Focus: Enterprise Digitisation is accelerating

|

Megatrend in Focus: Enterprise Digitisation is accelerating Insync Fund Managers March 2022 Whilst we focused on this exciting megatrend and Accenture last year, things are moving even faster than forecast and so a revisit is timely. Accenture is a prime holding for this megatrend and thus remains in the Insync portfolio. In their recent earnings call, they announced a very strong demand environment. This has induced double-digit growth in all parts of their business and also across all their markets, industries and services. Many of their clients are embarking upon bold transformation programs, often spanning multiple parts of their enterprise in an accelerated time frame. Macro-economics have little impact on these companies spend on digitisation. These clients recognize the need to transform almost all of their businesses, meshing technology, data and AI and with new ways of working and delivering their product or service to market. Current market gyrations have not changed the trajectory of our identified megatrends (including this one) in the Insync portfolio. Our companies such as Accenture continue to grow profitably at multiples many times that of GDP.

Insync's intense focus on the fundamentals, investing in businesses like Accenture that are compounding their earnings at high rates, gives us confidence that the portfolio is well positioned to deliver strong returns as volatility in markets subside. Stocks held by Insync possess:

Funds operated by this manager: Insync Global Capital Aware Fund, Insync Global Quality Equity Fund |

13 Apr 2022 - Central banks are going green to questionable avail while stirring risks

|

Central banks are going green to questionable avail while stirring risks Magellan Asset Management March 2022

Finland's forests, which cover more than 70% of the country, are the subject of a continent-wide debate on how to halve EU carbon emissions by 2030. Policymakers, environmentalists, companies and the public are arguing over whether the forests should remain untouched, and thus absorb carbon, or be used as biomaterial.[1] Environmentalists want the woodlands in Europe's most-forested country to remain pristine carbon 'sinks'. Finland's government, companies, especially the ones that help forestry products generate 20% of the country's exports, and much of the public want to find commercially viable solutions that alleviate warming risks. That an EU proposal released in mid-2021 favoured the carbon-sink option only intensified the debate. Perhaps the European Central Bank could sort it out? During the dispute over the forests in the euro-member Finland, the ECB declared mitigating climate change was a priority. The central bank said it will embed environmental goals within monetary policy because wild and warmer weather can affect "inflation, output, employment, interest rates, investment and productivity; financial stability; and the transmission of monetary policy".[2] The Bank of England,[3] the Bank of Japan,[4] the Federal Reserve[5] and Sweden's Riksbank[6] are among central banks to mix sustainability and monetary goals to different extents. They are among the 83-member Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System that seeks to "mobilise mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy". As part of their green focus, central bankers are calling for net-zero-emissions targets. As they warn of climate systemic risks, central bankers are seeking to use their regulatory powers to enforce climate-risk-based capital standards on banks, conduct climate-change stress tests on financial institutions and force companies to disclose carbon risks. They are under pressure to 'green' the corporate-bond portfolios they have amassed under quantitative-easing programs.[7] To propel the sustainable shift, governments are appointing climate-aware people to central-bank leadership roles. US President Joe Biden this year, to cite a prominent example, nominated former Fed governor Sarah Raskin to be the Fed's vice chair of supervision of the board of governors.[8] In 2020, Raskin slammed the Fed for giving emergency pandemic relief to "dying" fossil-fuel companies.[9] In 2021, she urged financial regulators to exercise their "existing powers" to mitigate climate change.[10] (Such comments appeared to prompt the Senate in March to block her appointment.) Many ask whether it's wise for central banks, which style themselves as above politics, to charge into an issue that governments are struggling to solve because, while the science is not contentious, the politics are. Amid such discussions, two questions stand out. The first is: Will central banks accomplish anything? Those who advocate that central banks consider climate risks say standardising climate-related disclosures and making them mandatory could improve the pricing of climate risks. They say central banks highlighting the long-term financial risks of climate change can only help the public swing behind a solution towards net-zero emissions. They say that central banks can embolden the stability of the financial system over the long term by limiting banking crises caused by a sustained change in weather patterns. Advocates say central banks elevating climate risks would make commercial banks more wary of adding to (and they might even reduce) the US$3.8 trillion major banks have committed to the fossil-fuel industry.[11] Some factors, however, suggest central banks might achieve less than they hope. First, it can be argued that climate change poses little risk to financial stability. Bushfires, droughts, heat waves, rising and warmer oceans, storms and the like have never in modern times triggered a systemic financial crisis.[12] The industries that lose from the shift to a low-carbon economy (so-called stranded assets) are unlikely to imperil the financial system either. It's usually the next big things that bubble to the point of threatening financial stability.[13] A study of financial crises, This time is different by Carmen Reinhard and Kenneth Rogoff, found one common theme behind eight centuries of financial folly; "excessive debt accumulation".[14] The second, perhaps surprising, reason central banks might make little headway for the environment is that banks don't appear to have been threatened by climate change and they seem capable of judging such risks for themselves. A 2021 Fed Bank of New York study of declared US disasters from 1995 to 2018 found US banks have learnt to manage climate risks and they gain from calamities. The study found that banks are adept at avoiding loans for, say, homes in harm's way and benefit from lending for rebuilding, "which actually boosts profits at larger banks". The study noted its findings "are generally consistent" with other studies on bank stability and disasters, even one conducted on banks in the hurricane-prone Caribbean.[15] The results, however, might be different if the world experiences a watershed increase in temperature. Third, central banks elevating the consideration of climate risks is unlikely to be a telling blow to fossil-fuel companies. If commercial banks were to restrict lending to or increase interest-rate charges for fossil-fuel companies, private financial firms are likely to buy these businesses cheaply, especially in the absence of a price on carbon. The Economist estimates that private equity firms have swooped on US$60 billion of dirty assets in the past two years.[16] Fourth, central banks have little legal basis on which to act on green lines.[17] Central banks lack authority to direct bank lending. Parliaments could give central banks these capabilities but it's likely such efforts would be as stillborn as most political efforts to mitigate the climate emergency. In the meantime, central banks can only target net-zero emissions - almost indirectly - by using their regulatory powers to highlight financial-stability risks. Last, there appears to be no link between interest-rate settings and a long-term meteorological event. "When it comes to saving the planet, central banks do not have a magic wand," says Jens Weidmann, former head of the Bundesbank (2011-2021).[18] The other overarching question with central banks going green is: What are the risks? The first is that central-bank climate risk management could clash with their mandates to keep inflation tame over the short and long term. The shift to a net-zero-emissions world stirs what economists call 'greenflation'. This is the term for when fossil-fuel prices jump because investment in climate-harming energy has fallen but demand for dirty power hasn't. Greenflation is already rife in Europe, especially the UK. The second hazard is that central banks might be adopting an explicit role of capital allocation, which breaches their principle of 'market neutrality'. Their climate stress tests, for example, might force banks to pull back from fossil-fuel assets. They are toying with tilting their asset-buying towards sustainable assets - something a Bank of England paper says defies calibration.[19] While central banks control the quantity of money, the allocation of money is a political choice for governments. Smudge the role of central banks and politicians and central-bank credibility and independence could be lost. A theoretical risk is that central banks might encourage a green investment bubble on that could metastasise into a systemic threat - think of it as a central-bank 'green put', even if there is no sign of one emerging. A fourth concern is that central banks might be in danger of 'mission creep', at the cost of their focus on inflation. What, for instance, is stopping central banks pursuing other worthy social goals such as reducing inequality (which is made worse by their quantitative easing)? Setting aside the debate about what central banks might accomplish, the risks show the use of public regulatory powers is a poor substitute for political solutions, even when none are appearing. The problem arising when government institutions step in because politicians can't sort out competing rights is that these bodies become politically tainted. It is best that central banks don't let climate-change priorities get in the way of their traditional tasks, which are hard enough to get right. To be sure, central banks recognise that governments and parliaments have "primary responsibility" to act on climate change.[20] Central banks certainly have a role in managing the short-term costs of combating climate change, especially greenflation. Government policies to mitigate the climate emergency could hurt the economy to the point of creating financial instability. But that's different from saying changed weather and stranded assets could. Central-bank stress testing demands higher capital requirements for credit cards and auto loans than for home loans or the highest-rated companies. It thus could be argued that central banks are already allocating capital and all they seek to do is extend those responsibilities to mitigating the impact of climate risks on the banking system. Plenty of studies, such as one in 2021 from the US's Financial Stability Oversight Council, warn that climate change poses "an emerging and increasing threat" to financial stability.[21] What is more certain is the solutions to achieving net-zero emissions need to come from the political process - where they are being thrashed out for Finland's forests. The conflict of interest UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson this year has faced the threat of a leadership challenge as fellow Conservative MPs (and the public) sickened of endless scandals. These outrages included that Downing Street partied at the height of the pandemic while enforcing strict social restrictions that even prevented relatives being with the dying. They included allegations that Johnson approved the evacuation of zoo animals from Afghanistan while UK nationals were left behind when the Taliban last July took control of the country. The issue, however, commentators said, shaping as the most damaging blow for Johnson is economic. In February, the energy regulator told UK households their electricity and natural-gas bills could soar 54% come April when regulatory price caps are adjusted for prevailing prices. The average household's annual utility bill is forecast to jump by 700 pounds to about 2,000 pounds.[22] Energy prices are surging in the UK because the net-zero-emissions Johnson administration has deterred investment in fossil-fuel energies and renewable-energy companies are struggling to produce enough power to make up for the shortfall in climate-damaging-generated power. (One mishap was that an unusual lack of wind failed to power wind farms while Russia's invasion of Ukraine has only added to energy costs.) The higher power bills come with another blow for UK household budgets. The other battering is higher interest rates. In March, the Bank of England raised its key rate for the third consecutive month. The central bank in March lifted its benchmark rate by 25 basis points to 0.75% because it expects higher energy prices, exacerbated by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, to drive annual inflation above 8% within months. The most recent report shows that steeper energy costs boosted UK inflation to 6.2% in the 12 months to February, a 30-year high and more than triple the Bank of England's 2% inflation ceiling. This situation encapsulates the greatest quandary for central banks. Policies such as carbon pricing to reduce the production and usage of fossil fuels are likely to boost inflationary pressures (even if it only shows up directly as a one-off jump in inflation gauges). The greatest contribution central banks might make in the quest to mitigate climate change could be to ensure their economies flourish in a low-inflationary way over the longer term, while ensuring financial stability. That would create the most favourable milieu for the political process to tackle climate change, as messy, protracted and contentious as that method might be. See the debate over Finland's forests. Author: Michael Collins, Investment Specialist |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund [1] See, 'Finland's forests fire up debate over EU's strategy for going green.' Financial Times. 1 September 2021. ft.com/content/b7e8ae66-f002-4361-84eb-6888ded2ec87 [2] European Central Bank. 'ECB presents action plan to include climate change considerations in its monetary policy strategy.' Media release. 8 July 2021. ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2021/html/ecb.pr210708_1~f104919225.en.html [3] Bank of England. 'Climate change.' bankofengland.co.uk/climate-change [4] Bank of Japan. 'Climate change.' boj.or.jp/en/about/climate/index.htm/ [5] The Federal Reserve. 'Climate change and financial stability.' 19 March 2021. federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/climate-change-and-financial-stability-20210319.htm [6] Sveriges Riksbank. 'Sustainability strategy for the Riksbank.' 16 December 2020. ypfsresourcelibrary.blob.core.windows.net/fcic/YPFS/sustainability-strategy-for-the-riksbank.pdf [7] Bank of England 'Climate change' for its climate goals. bankofengland.co.uk/climate-change [8] The White House. 'President Biden nominates Sarah Bloom Raskin to serve as vice chair for supervision of the Federal Reserve and Lisa Cook and Philip Jefferson to serve as governors.' 14 January 2022. .gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/14/president-biden-nominates-sarah-bloom-raskin-to-serve-as-vice-chair-for-supervision-of-the-federal-reserve-and-lisa-cook-and-philip-jefferson-to-serve-as-governors/ [9] Sarah Raskin. 'Why is the Fed spending so much money on a dying industry?' 28 May 2020. nytimes.com/2020/05/28/opinion/fed-fossil-fuels.html [10] Sarah Raskin. 'Changing the climate of financial regulation.' Project Syndicate. 10 September 2021. project-syndicate.org/onpoint/us-financial-regulators-climate-change-by-sarah-bloom-raskin-2021-09 [11] World Economic Forum. 'How central banks are tackling climate change risks.' 4 May 2021. weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/central-banks-tackling-climate-change-risks/ [12] SeeJohn Cochrane. 'The fallacy of climate change risk.' Project Syndicate. 21 July 2021. project-syndicate.org/commentary/climate-financial-risk-fallacy-by-john-h-cochrane-2021-07. See also, 'Could climate change trigger a financial crisis?'. 4 September 2021. The Economist. economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/09/04/could-climate-change-trigger-a-financial-crisis [13] A problem could arise if climate regulations ensured rapid collapses. But governments would be at fault then, not central bankers. [14] Carmen Reinhard and Kenneth Rogoff. 'This time is different'. Princeton University Press. 2009. See preface. [15] Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 'How bad are weather disasters for banks?' November 2021. Revised January 2022. newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr990 [16] The Economist. 12 February 2022. 'The truth behind dirty assets.' economist.com/leaders/2022/02/12/the-truth-about-dirty-assets [17] Congress, for example, has given the Fed a triple mandate to achieve "maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates. The triple mandate is often referred to as a 'dual mandate' because people ignore the goal of moderate rates. See the Federal Reserve. 'Federal Reserve Act.' 'Section 2A. Monetary policy objectives. federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section2a.htm [18] Jens Weidmann. 'Bundesbank chief: How central banks should address climate change.' Financial Times. 19 November 2020. ft.com/content/ed270eb2-e5f9-4a2a-8987-41df4eb67418 [19] Bank of England. 'Options for greening the Bank of England's Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme.' 21 May 2021. bankofengland.co.uk/paper/2021/options-for-greening-the-bank-of-englands-corporate-bond-purchase-scheme [20] European Central Bank. Op cit. [21] US Department of the Treasury. 'Financial Stability Oversight Council identifies climate change as an emerging and increasing threat to financial stability.' 21 October 2021. home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0 telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/02/13/net-zero-may-become-divisive-brexit/ [22] See Liam Halligan. 'Net zero' may become as divisive as Brexit.' The Telegraph. 13 February 2022. telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/02/13/net-zero-may-become-divisive-brexit/ Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 ('Magellan') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should read and consider any relevant offer documentation applicable to any investment product or service and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making any investment decision. A copy of the relevant PDS relating to a Magellan financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any strategy, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to be implemented and its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any trademarks, logos, and service marks contained herein may be the registered and unregistered trademarks of their respective owners. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan. |

12 Apr 2022 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quay Global Real Estate Fund (AUD Hedged) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Talaria Global Equity Fund - Currency Hedged (Managed Fund) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Metrics Credit Partners Wholesale Investments Trust |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Merkle Tree Capital Digital Asset Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ListedReserve Managed Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 650 others |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.JPG)