NEWS

14 Jun 2022 - Record high inflation could trigger a fresh eurozone financial crisis

|

Record high inflation could trigger a fresh eurozone financial crisis Magellan Asset Management May 2022 Italy's 66th post-war government collapsed in January 2021 when Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte was forced to resign after former premier Matteo Renzi removed his minor Italia Viva party from the ruling coalition. President Sergio Mattarella encouraged the parties to revive the alliance so he could avoid calling a snap general election during a pandemic. But the talks went nowhere. As concerns grew that any election might usher right-wing populists into power, Mattarella pulled off a masterstroke. In early February, Mattarella unexpectedly contacted Mario Draghi; yes, 'Super Mario' who saved the euro in 2012 with his 'whatever it takes' comment. Mattarella asked the chief of the European Central Bank from 2011 to 2019 to begin talks to form a 'national unity' government. Within days, Draghi had won a parliamentary majority to become Italy's 29th prime minister since 1946 and its fourth unelected (or 'technocratic') premier since 1993.[1] Investors were pleased. On February 13 when Draghi assumed office, 'lo spread' - the yield at which Italian 10-year government bonds trade over their German equivalents, a number that is judged the bellwether of EU economic and political risks - had narrowed to a five-year low of just under 100 basis points. Draghi's government retains the confidence of investors yet lo spread has widened to 200 basis points (as the German 10-year bond topped 1% for the first time since 2015).[2] What malfunction occurred that widened the gap towards the 300 basis-point level that is seen by many as the tripwire for a crisis? None that was Draghi's fault. The culprit, like elsewhere in the world, is inflation. Eurozone inflation has climbed to its highest since the euro was created in 1999. Consumer prices surged 8.1% in the 12 months to May due to the ECB's promiscuous monetary policy, mammoth fiscal support during the pandemic, rising energy prices due to the switch to renewables, and supply blockages created by pandemic disruptions. The way Russia's war on Ukraine has boosted energy, commodity and food prices is likely to keep eurozone inflation elevated. The ECB has one objective; to maintain price instability, which is interpreted as keeping inflation below 2%. The central bank modelled on the inflation-hating Deutsche Bundesbank has little choice but to tighten monetary policy when inflation is nearly four times its target. Since 2016, the ECB's key rate has stood at 0%, while the overnight deposit rate has been negative since 2014 (and at a record minus 0.5% since 2019).[3] When the pandemic struck, the ECB added to various asset-buying programs[4] that gained heft when the bank first undertook quantitative easing in 2015. Over the past seven years, the central bank has purchased 3.9 trillion euros of eurozone assets, including 723 billion of Italian public debt, an amount equal to nearly 40% of Italy's GDP.[5] Given the record inflation, talk is mounting the ECB in July will raise rates for the first time since 2011, in what would be the first step towards boosting the key rate to a 'neutral' level of about 1.5% next year. The central bank is curtailing, and intends to end, its asset purchases.[6] Many central banks are raising key rates to tame inflation. For most countries, the main threat is the resultant slowing in economic growth boosts the jobless rate, perhaps to worrying levels if economies slump into recession. The ramifications of tighter monetary policy for the 19-member eurozone are wider and more concerning for three reasons. The first is the ECB is poised to stop acting as the buyer of last resort for its almost-bankrupt 'Club Med' members such as Italy, where gross government debt stood at 151% of GDP at the end of 2021.[7] No financier of government deficits (as some see it) for indebted sovereigns, especially Italy, will likely trigger a bond sell-off that puts the finances of debt-heavy governments on an unsustainable footing. Rising yields might restart the 'doom loop' that triggered the collapses of Greece, Ireland and Spain from 2010, whereby national bank bond holdings held as capital reserves plunge in value and the national government and commercial lenders become entwined in a downward spiral. The ECB would be exposed as lacking any credible way to quell such a government-bank suicide bind short of resuming the asset-buying that fuels the inflation it seeks to kill. The second way tighter ECB monetary policy is troubling is that the resultant economic downturn will remind indebted euro-users that they have no independent monetary policy to help their economies, nor a bespoke currency they can endlessly print to meet debt repayments, or devalue to export their way out of trouble. The only macro tool domestic policymakers possess is fiscal policy. The problem is many indebted governments are already running large fiscal deficits - Rome's shortfall over 2021 stood at 7.2% of GDP[8] and is forecast to be 6.0% in 2022[9] - and their debt loads mean these dearths can't be widened or prolonged. As talk mounts that indebted countries should quit the euro to reinstall the other macro tools, populist Italian politicians are bound to rekindle plans for a parallel currency as the least traumatic way for Italy to readopt the lira. The third means by which higher inflation is poisonous for the eurozone is that it creates a fissure between the area's creditor and debtor nations that would make it harder to find durable solutions for the euro. Inflation-phobic but inflation-ridden Germany and other creditors such as Finland and the Netherlands will squabble with France (government debt at 113% of GDP), Greece (193%), Italy, Portugal (127%) and Spain (118%) over how far the ECB should go to rein in inflation. The leaders of the creditor countries will be under domestic political pressure to ensure the ECB smothers inflation. They will battle with debtor leaders over how the ECB might support tottering governments and wobbly national banks sitting atop troubled economies. In line with this hawk-dove split, the Netherlands central bank chief Klaas Knot in July became the first ECB policy-board member to call for the bank to raise its key rate by 50 basis points to tackle inflation.[10] To maintain its inflation-fighting credentials, the ECB must raise interest rates enough to tame inflation, even if that stance crushes economic growth. The core concern of such tight monetary policy is that it will expose how the euro's flawed structure - that it is a currency union without the necessary political, fiscal or banking unions - has become explosive due to the large debts of southern eurozone governments. To be sure, policymakers are likely to once again thrash out some last-minute fudge that defers a denouement on the euro's fate. But temporary solutions are only, well, temporary and the euro needs a durable resolution. The indebted south could win the political tussle such that the ECB never makes a serious attempt to tame inflation. Due to generous pandemic support, creditor nations have higher government debt-to-GDP ratios - Germany's is 69%, the Netherland's 52%. They thus might tolerate faster inflation as it improves their debt ratios if their economies hold up. But that path might only delay tighter monetary policy and subsequent detonations. The war in Ukraine might undermine eurozone economic growth enough to quell inflation without the ECB doing much. The cost of servicing public debt, while rising, is still historically low, which reduces the likelihood of missed debt payments and a crisis. Eurozone governments are restarting efforts to create a proper banking union, which would mean common bank rules and eurozone, rather than national support for troubled banks.[11] But creditor nations don't want to be part of a mutual deposit insurance scheme if that means subsidising Italian banks holding Rome's debt. Nor do debtor governments want to join a banking union that could restrict their banks buying their bonds to support them. Lo spread is well short of the post-euro record 556 basis points it reached in 2011 during the first eurozone crisis that was triggered by the current-account imbalances among members.[12] But Rome's debt was only 120% of GDP then, and that gap narrowed only due to ECB support that is now waning because the problem today is inflation, not skewed trade and investment flows. Germany's economic slump and dislike of inflation will ensure Berlin pressures the ECB to prioritise inflation. Lo spread could widen enough to threaten a flawed currency union, especially if member countries are squabbling over solutions. While Draghi the central banker could bluff investors, Draghi the politician has no similar obvious masterstroke. Of note too is that Draghi's prime ministership will likely end when Italy holds a general election next year in Europe's spring that is likely to usher right-wing eurosceptics into power. To all the world's problem, be prepared to add elevated doubt about the euro's long-term future. The currency swap In 1948, Chris Howland was a 20-year British private who was the most popular radio DJ in northern Germany. On the night of June 17, two British military policemen appeared at the radio station in Hamburg where Howland worked. They made Howland sit up all night before allowing him at 6.30 am to open a sealed envelope and read the content on air. The news? The military government of Britain, France and the US from June 20 would introduce a new currency. Every German would receive 40 new Deutsche marks, which had been printed in the US and shipped in wooden crates stamped 'Doorknobs', in exchange for 60 Reichsmarks. Any other swastika-emblazoned Reichsmarks people held were made worthless come June 21.[13] A 'currency reform' of some sort was expected. But still. It's estimated that 95% of Reichsmarks were destroyed without replacement and savers were left with only 6.5% of their assets. The instantaneous currency switch and savings savaging were at the heart of measures under the Marshall Plan designed to revive Germany's economy at a time when millions of Germans were starving, inflation was rife, the currency untrusted and bartering prevalent. The steps, which in the absence of Russian knowledge sparked the Berlin Blockade,[14] worked. The economic revival in the French, UK and US zones that became West Germany was credited with helping Germany adopt a new constitution in 1949 known as the Basic Law. The currency changeover on top of the rampant post-war inflation and the hyperinflation of the early 1920s left a legacy. Germans adopted a mentality that the value of the Deutsche mark must be protected above all. This job was given to the Bundesbank when it was established in 1957 as the world's first and only central bank still to be granted independence under its country's constitution (whereas other central banks are granted 'independence' through acts of parliament or the goodwill of the executive).[15] Come 1993, Germany's Constitutional Court confirmed that under the Basic Law the Bundestag (parliament) only had the authority to ratify the Maastricht Treaty that created the euro if the European monetary union was in Germany's interest. The test? "The future European currency must be and remain as stable as the Deutsche mark," the court decreed.[16] Thus the ECB ended up with the same primary objective as the Bundesbank; namely, to maintain price stability. In Germany, the ECB's loose monetary setting and the inflation unleashed are seen as a betrayal. To the German public, tabloid media and even the German 'father of the euro' Otmar Issing, the ECB is modelled more on Italy's economic mismanagement pre-euro (when Rome's main policy response was to devalue the lira). Issing, the ECB's first chief economist, said the ECB has "lived in a fantasy" that downplayed the danger of inflation and thus the bank "has contributed massively to this trap in which it is now caught".[17] The ECB lax stance has wiped out returns on German savings, which is seen as income foregone to subsidise lazy southern Europeans.[18] High inflation stings Germans because few invest in equities or other 'growth' assets that might act as a hedge against inflation. Most German savings head to small regional savings and co-operative banks that offer low deposit rates. The German public is unlikely to feel more generous towards the indebted south if interruptions to energy and other imports from Russia send the German economy into recession.[19] But, as pessimism grows about global prospects, the economic outlook of inflation-tolerant and Russian-gas-dependent Italy is dimming too. Although Italy's economy is supported by consumer savings built up during lockdowns and 192 billion euros from the EU's 750-billion-euro Covid recovery fund, higher energy prices and other tremors from the Ukraine war could slow growth enough to send the country into recession.[20] Many fret about the trouble to be ignited when the ECB halts its asset buying, given how precarious are Rome's finances - the country has the largest budget deficit in the eurozone and the worst public debt ratio after Greece (193%).[21] In case of any crisis centred on Italy, policymakers have options such as loans from the EU rescue fund and linked ECB bond purchases of struggling members. But such aid would require approval from Germany's Bundestag and other creditor-nation parliaments. Another option is the one revealed when Draghi and French President Emmanuel Macron signed a joint letter last December that implicitly called for the transfer of all eurozone government debt since 2007 to a debt-management agency. But Germany and many other euro members would oppose such subterfuge.[22] It's probable that sometime soon the talents of Draghi the unelected politician and other policymakers will be tested. Lo spread will reveal what bond investors think. What's unlikely in any upcoming crisis, however, is any solution that cements the euro's future. By Michael Collins, Investment Specialist |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund [1] In 1993, Bank of Italy Governor Carlo Azeglio Ciampi was drafted as prime minister. At the height of the sovereign debt crisis in 2011, Mario Monti, who'd spent a decade at the European Commission, was appointed PM. In 2018, rival populist parties tapped Conte, a law professor at a university in Florence, to be PM. A list of Italian prime ministers can be found at: wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_prime_ministers_of_Italy[2] The gravest scare for investors during Draghi's time as prime minister occurred in January this year when Italy's parliament failed to elect a new president in seven ballots held over a week and Draghi was touted as the next head of state (and seemed interested in the role). But that would have once again meant a snap general election that might have jetted right-wing populist parties into power. That outcome was avoided when MPs re-elected Mattarella even though the 80-year-old had rejected a second term. Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 ('Magellan') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should read and consider any relevant offer documentation applicable to any investment product or service and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making any investment decision. A copy of the relevant PDS relating to a Magellan financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any strategy, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to be implemented and its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any trademarks, logos, and service marks contained herein may be the registered and unregistered trademarks of their respective owners. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan. |

10 Jun 2022 - Why country risk matters

9 Jun 2022 - Is this a buying opportunity?

|

Is this a buying opportunity? Equitable Investors May 2022 "RECAPITALISATION" OPPORTUNITY The $US146 billion of equity capital raised globally in the March quarter of 2022 sounds like a huge number but was down 69% from $US476 billion a year earlier and 58% from the December quarter (using dealogic data). The current quarter is running lower still. We have identified almost 400 "cash burners" on the ASX (ex resources). Nearly half of these cash burners did not have the funds to make it past 12 months based on their March quarter cash burn. It may not be a complete surprise to you that the sector with the most companies facing one year or less of cash funding is Software and Services. Biotech and Health Care unsurprisingly represent nearly 30% of these companies. The great opportunity in this is for investors to identify situations where capital availability can make a huge difference to valuation, either in isolation or with a few changes and greater fiscal discipline. We think this "recapitalisation" opportunity is a huge opportunity and an exciting time for a firm such as Equitable Investors that applies bottom-up, fundamental research and constructively engages with companies. We are inviting follow-on and new investments in Dragonfly Fund to pursue such opportunities over the next 12 months. Applications (for wholesale investors only) can be made here.

Funds operated by this manager: Equitable Investors Dragonfly Fund Disclaimer Nothing in this blog constitutes investment advice - or advice in any other field. Neither the information, commentary or any opinion contained in this blog constitutes a solicitation or offer by Equitable Investors Pty Ltd (Equitable Investors) or its affiliates to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. Nor shall any such security be offered or sold to any person in any jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation, purchase, or sale would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. The content of this blog should not be relied upon in making investment decisions.Any decisions based on information contained on this blog are the sole responsibility of the visitor. In exchange for using this blog, the visitor agree to indemnify Equitable Investors and hold Equitable Investors, its officers, directors, employees, affiliates, agents, licensors and suppliers harmless against any and all claims, losses, liability, costs and expenses (including but not limited to legal fees) arising from your use of this blog, from your violation of these Terms or from any decisions that the visitor makes based on such information. This blog is for information purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice. The information on this blog does not constitute a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Although this material is based upon information that Equitable Investors considers reliable and endeavours to keep current, Equitable Investors does not assure that this material is accurate, current or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Any opinions expressed on this blog may change as subsequent conditions vary. Equitable Investors does not warrant, either expressly or implied, the accuracy or completeness of the information, text, graphics, links or other items contained on this blog and does not warrant that the functions contained in this blog will be uninterrupted or error-free, that defects will be corrected, or that the blog will be free of viruses or other harmful components.Equitable Investors expressly disclaims all liability for errors and omissions in the materials on this blog and for the use or interpretation by others of information contained on the blog |

8 Jun 2022 - With markets falling, is it safe to invest again?

|

With markets falling, is it safe to invest again? Montgomery Investment Management 26 May 2022 In the famed 1970s thriller, Marathon Man, Nazi dentist Dr Christian Szell - who is looking for a stash of stolen diamonds - repeatedly asks the character played by Dustin Hoffman "Is it safe?" Right now, many people are likely asking the same question about investing in the share market. With the distraction of local politics behind us, investors can return to matters that will shape their short and medium-term returns. Given a lack of clarity about where the safe havens are, and notwithstanding the supply shocks associated with the war in Ukraine and the recent shuttering of China's economy, what follows is a summary of the issues confronting equity markets and a possible answer to the question of whether it is time to add to your investment in equities. InflationWidespread and stubborn U.S. inflation, driven by surging oil and rents, as well as rising wages, has inspired inflation expectations for next year to more than six per cent, from near one per cent in 2020. U.S. core Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation, which excludes more volatile food and energy, has risen from sub-two per cent in the first quarter of 2021 to an annual rate of 4.9 per cent, the highest since September of 1983. Slowing U.S. economic growthEquity investors are of course aware of this trend and the persistence of supply chain bottlenecks that are in no small part responsible. Perhaps less obvious, but no less concerning, are the rapid reductions being applied by forecasters to U.S. economic growth. According to Bloomberg, forecast U.S. GDP growth for 2022 was above four per cent back in Q3'21 but has recently plunged towards 2.75 per cent. Meanwhile the 2.5 per cent GDP forecasts for 2023 in place at the beginning of this year have given way to forecasts of 2.1 per cent. Falling earningsSlowing U.S. GDP growth is important for share prices. Remembering that much of the equity market correction to date has been the consequence of PE compression - which always accompanies rising rates and accelerating inflation - a slowing rate of growth raises the spectre of reduced earnings. And when the 'E' in the PE ratio also declines, equity market losses can and often compound. As waves of liquidation have hit U.S. equities amid a winding back of the Federal Reserve stimulus and rising interest rates, declining total returns for the S&P500 have exceeded the total return losses in treasuries. These returns are highly correlated to 12-month forward S&P500 earnings per share estimates. Consequently, the earnings estimates are now declining, from growth of circa 55 per cent year-on-year, to 27 per cent today. The winding back of earnings expectations, and the broadening of the bear market, may still have some way to go, even as 50 per cent of NASDAQ Composite constituents - the most vulnerable being thematic and concept stocks, small cap tech and small cap growth, for example - have fallen by more than 50 per cent, and 72 per cent of constituents have fallen by more than 25 per cent (see Table 1.). Table 1. Bear market in stealth mode Declining U.S. real disposable incomesHeaping burning coals on the declining earnings outlook will be the decline in real disposable incomes, which are near minus 12 per cent year-on-year and represent the sharpest decline since at least 1960. The decline is of course partly due to the high support/stimulus payments received last year but much of it can also be attributable to the sharp rise in inflation. Historically, when real income contractions of this magnitude have occurred, they were followed by a marked slowdown in consumer spending. We believe, therefore, at the very least, investors should not expect upgrades from, or re-ratings for, companies exposed to consumers just yet. Is it time to invest?However, the baby is being thrown out with the proverbial bathwater and high-quality names across a broad variety of sectors and industries are now being sold down too. As we have witnessed many times in the last three or four decades, ultimately, indiscriminate selling gives way to discernment and finally selective buying. A capitulation sell-off may therefore eventually give way to another once-in-a-decade opportunity to improve the general quality of portfolios and lock in superior returns. Remember, the lower the price one pays, the higher the return. What are the factors investors should be watching to decide if it is safe to dip one's toe back in the water?The current sell-off has been largely macro-driven. Concerns about inflation and rising interest rates, and now slowing growth (stagflation), are principally responsible for the current reassessment of equity investor returns. These seem likely to remain this year. It seems reasonable to conclude the expectation of good news on these fronts will be necessary for the current 'risk-off' sentiment to ease before reversing. The question of course, is where are the revelations going to be? Will slowing growth lead to recession, which restores bonds as a safe haven, reducing their yield and setting equities up for a recovery post-recession? Or will we see high inflation and strong economic growth, empowering only companies with pricing power to improve margins through a combination of higher volumes and higher prices? Finally, do we end up with Jerome Powell's 'soft-landing' scenario, which will be positive for both equities and bonds? In the short run, the market seems very oversold making it susceptible to a sharp short-term recovery (Figure 1.) Figure 1. Negative change in PE historically significant and fully factored in rising rates As can be seen in Figure 1., the pace of PE compression is historically significant and is nearing a point (red line) from which PEs have historically expanded again. The PE compression reflects rising interest rate expectations but importantly, however, it does not appear the market has factored in any recession or even any slow-down in earnings. The slow-down in earnings growth estimates however still suggests investors are factoring in some growth. And investors should not ignore the tax-like impact on consumers and growth from the combination of rising interest rates, rising fuel costs and the rising U.S. dollar (which of course saps capital from and fuels inflation for importing nations). The market has not factored in a contraction in earnings (keep also in mind the very steep slump in real disposable income cited above) and for this reason many commentators believe further declines in the stock market should be expected. And unlike previous bear market episodes, the Federal Reserve does not appear to be coming to the rescue of investors. Indeed, if anything, the Fed's Jerome Powell has toughened his Hawkish stance. Meanwhile, as liquidity is being withdrawn, money supply growth continues to slow relative to bank credit growth, meaning there is less liquidity for financial assets. Finally, while some commentators and macro economists point to evidence, and warn, of more frequent bear markets (US S&P500 drawdowns of 20 per cent or greater) during periods of rising inflation (Figure 2.), I note my firm belief long-term declines in union membership and rapid advancement in autonomous technology will keep a lid on long-term wages growth and ultimately on inflation. Figure 2. S&P500 sell offs during rising inflation (1965-80) and declining inflation Investors should be sharpening their pencils and working on the stocks and funds in which they plan to invest, in preparation for making additional equity market investments. Author: Roger Montgomery, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer Funds operated by this manager: Montgomery (Private) Fund, Montgomery Small Companies Fund, The Montgomery Fund |

8 Jun 2022 - Why 15 stocks are all you need

|

Why 15 stocks are all you need Claremont Global May 2022

With a mandate of owning 10-15 stocks, I am often asked: "How do I sleep at night given the concentration risk?" This has been a familiar refrain for most of the 25 years I have been managing client capital and where I have always run concentrated portfolios with 10-25 stocks. The thinking suggests that with a concentrated portfolio, you are running excess risk and one would be better served having a more "diversified" portfolio. My answer is always the same - it all depends on how you define risk. If you define risk as the chance of underperforming an index or benchmark in the short term - then I would agree this is "risky". This is the classic fund manager's "career risk" - the chance of underperforming a benchmark and putting your job on the line or losing client FUM. In the words of John Maynard Keynes: "It is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally". But to earn returns that are better than the market, it is really quite simple - you have to own portfolios that are different from the market. Robert Hagstrom in his excellent book The Essential Buffett - timeless principles for the New Economy ran a 10-year study from 1987-96 where he had a computer randomly assemble 3,000 portfolios from 1,200 companies and broke the results down as follows:

It is interesting to note the 15-stock portfolio achieved an average return not much different to the 250-stock portfolio but with a much wider range of outcomes (i.e. much higher career risk!). However, the chances of beating the market were also more than 13 times higher. In addition, Lorie & Fisher showed in their 49-year study of NYSE-traded stocks between 1926-65 that 90 per cent of stock risk can be diversified with a 16-stock portfolio. But we define risk as the possibility of permanently impairing client capital or not achieving a satisfactory return for the risk taken. And we target a long-term return of eight to twelve per cent per annum over a five to seven-year period. We believe a permanent impairment to capital is most likely to arise in the following ways: Buying heavily leveraged businessesMany management teams are very happy to layer on debt in the good times by "returning capital" to shareholders and achieving artificial EPS growth to satisfy short-term and poorly defined incentive targets. There is no better example of this than the actions of American Airlines in the five years to 2019. The company "returned" $13bn in buybacks - this was despite the fact there was no capital to return, as free cash flow over the period was a NEGATIVE $3.2bn! The ratio of debt to earnings before income, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) was 4.2-times in 2019 at the peak of the cycle. In our opinion this is highly irresponsible, given the industry already has a high degree of operational gearing, has a large amount of off-balance sheet debt in the form of leases and is vulnerable to rising oil prices. And then when tough times hit, these companies go cap-in-hand to the government and/or shareholders to repair balance sheets at very depressed equity prices, resulting in severe value destruction. By contrast, our portfolio has a weighted net debt/EBITDA of 0.7x. Excess leverage is just not a risk we are willing to run. Balance sheet strength is a given in our portfolio. We know that the future is always uncertain and rather than trying to forecast when the good times will end (folly in our opinion), we assume that recessions are a natural part of economic life and we prepare accordingly. The added benefit of this is that when recessions occur, our companies can play offence - buying quality assets or their own shares at favorable prices and maintaining or even increasing the dividend. We have companies in our portfolio that have consistently paid rising dividends for over 40 years. Buying businesses that rely on an accurate forecast of some hard-to-predict variableThese variables can be interest rates, moves by the Federal Reserve, commodity prices, regulation, innovation and election results, amongst many others in a complex world. In 2016 I didn't know many people who predicted Trump would be elected ― and for those who did, how many predicted that markets would rally? Or in March of this year, who would have thought the market would be at an all-time high in December, when the global economic contraction has been the largest since the Great Depression? Another favourite of mine in recent years has been buying banks on the "yield steepening trade", only to then see rates collapse. Or the oil majors in 2014, who spent billions on exploration with a forecast of oil being above $100 a barrel, only to see oil collapse with the advent of shale oil. We deliberately avoid businesses that rely on us correctly forecasting commodity prices, interest rates, elections, drug discoveries, economic growth or political outcomes. Experience has taught us that very few people are able to do this on a consistent basis. Yogi Berra put it well: "Forecasts are hard, especially about the future". Buying inferior businesses with no competitive advantageOver time, competition does a pretty good job of taking away excess returns for most businesses. And over time, it is very hard for an investor to earn a return much different than the underlying economics of the business one owns. If an investor wants to earn an excess return, logic suggests that the best place to start is with owning businesses that themselves earn excess returns on shareholder capital. Superior returns on capital normally arise from some form of competitive advantage - be it a brand, network effect, scale, reputation, data, client relationships, IP or technology. But the allure of buying "cheap" businesses is often too much for some. Even Warren Buffett himself made this mistake when buying textile company Berkshire Hathaway at a steep discount to its underlying asset value. But as he said many years later, once he came to realize his mistake and finally exited the business: "Berkshire Hathaway's pricing power lasted the best part of a morning". Our preference is to own businesses that have been proven over many years and cycles. The average age of our businesses is over 70 years, with the oldest dating back to the end of the US Civil War. They have been tested through wars, product cycles, recessions, political upheaval, inflation and financial crises. The competitive advantage in our portfolio is evidenced by an operating margin of 27 per cent and a return on invested capital of 18 per cent - both over 2x the average listed business. It is interesting to note the average listed business earns a return of 9 per cent - not far from the level equities have actually achieved over the long term.

Aggressive management or those who allocate capital poorlyUnfortunately, it is a fact of life that the people who end up running businesses are often no "shrinking violets". They are usually very confident in their ability and their normal starting point is to aggressively "grow the business". This can often involve straying away from their core competence into new areas, where their "skill" will translate into superior returns to shareholders. The worst situation occurs where management take on a lot of debt at the peak of the cycle, pay an inflated price for an asset, heap goodwill on the balance sheet, only to reverse the deal many years later ― and more often under new management. A classic example of this is GE, who took a very good industrial business and then ventured into credit cards, property, insurance, media ... the list goes on. The end result was to take a AAA rated balance sheet and turn it into one that is now barely above junk status. Or closer to home - who can forget Woolworths ill-timed home improvement venture against the toughest of competitors, or even Bunnings themselves and their venture into the UK? Would it not have made sense to focus capital on the competitive advantage that made the company a market leader in the first place and then return excess capital to shareholders? And finally, my all-time favorite - the Vodafone purchase of Mannesmann at the peak of the TMT mania for $173bn, which saw Vodafone CEO Chris Gent earn a bonus of $16m for the "value" he created. In 2006, Vodafone quietly wrote the asset down by $28bn, but not before Sir Chris Gent received a knighthood for "services to the telecom industry." I wonder whether he should have received the highest German accolade "for services to the German pension fund industry." To quote Michael Porter, the doyen of competitive advantage: "The biggest impediment to strategy and competitive advantage is an overly reliant focus on growth". By contrast, we prefer our management teams to relentlessly focus on competitive advantage, customers, employees, communities and reinvest back in the business for the long term. And once this is done, to make sensible bolt-on acquisitions, pay dividends and buy back their stock when it is decent value. The last trait is very hard to find - there are very few management teams who treat buying their shares like they would any other acquisition. For most management teams, the logic is if I can borrow at, say 2 per cent, as long as I pay no more than 50x earnings - this enhances earnings per share. And unfortunately, most management teams will happily buy their stock in bull markets using cheap debt, only to stop this when their shares are cheap, as this is the "prudent" thing to do. Buying businesses at prices that are well above their fair valueEven if one buys businesses that have superior economics, strong balance sheets and are well managed - even the most disciplined can be lured into paying inflated prices, especially in the upper reaches of a bull market. The narrative always follows a similar pattern that excess growth will last forever, interest rates will never rise, the company has changed (very few do), the company deserves a lower beta and the list goes on. When valuing companies, we do not change our discount rates, terminal growth assumptions, or market multiples, preferring to use "through the cycle" value inputs. Neither do we use a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or beta to justify higher prices. Read any book by the doyen of valuation, Aswath Damodaran, and he will argue that if you are to drop your risk-free rate, you should also drop your terminal growth rate. This makes sense as a lower risk-free rate suggests a lower nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate. Yet, in the upper reaches of a bull market, it is not uncommon to see lower risk-free rates and higher terminal growth rates to justify valuations! ConclusionSo, to return to the original client question posed at the beginning of this article: "How do I sleep well at night with only 10-15 stocks?" The question assumes that I would sleep better if we owned more stocks. Well, to do that, we would have to add lesser quality names or those with lower expected returns. Would I sleep better then? It would decrease our research intensity, whilst potentially lowering the quality and/or the expected return of the portfolio. I could load up on "cheap" bank stocks but would now be exposing myself to balance sheet risk ― at 20x geared, these businesses can literally go to zero as we saw in the global financial crisis (GFC) ― as well as interest rate risk, economic risk and a large amount of regulatory risk (witness the halting of dividends in Europe recently). Or, I could load up on "cheap" oil stocks, but I would be up late at night poring over demand/supply dynamics, vaccine developments and economic data. These are areas where the future is difficult to define and instead of allowing me to sleep better, it would have the opposite effect! This is not our way. Instead, we prefer to construct a portfolio of 10-15 high quality businesses, whose earnings have a very good chance of growing well ahead of inflation over a long period of time ― and when the inevitable bad times come, we know we own time-tested business models, fortress balance sheets and seasoned management teams that will get us through to the other side. We may see share prices fall ― in some cases quite dramatically like the GFC or the March sell-off ― but for those with the fortitude to see it through, this is unlikely to be a permanent destruction of capital. This approach has served me well through hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, the TMT bubble, the GFC, the European debt crisis and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic. For one known to like his sleep, it allows me to sleep well. And more importantly, our clients too. Author: Bob Desmond, Head of Claremont Global & Portfolio Manager Funds operated by this manager: |

7 Jun 2022 - The Expanding Role of ESG in Private Debt

6 Jun 2022 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Milford Conservative Fund | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Milford Trans Tasman Equity Fund |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Ruffer Total Return International - Australia Fund |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| GAM LSA Private Shares AU Fund | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Tectonic Opportunities Fund | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 650 others |

6 Jun 2022 - Markets pivot from reflation to deflationary bust

|

Markets pivot from reflation to deflationary bust Watermark Funds Management May 2022 MONTH IN REVIEW The Australian share market saw a small contraction in April with the All-Ordinaries Index down 0.83%, much less than the 8.7% contraction seen in the S&P 500. The modest move in the index disguised material moves in underlying sectors. Sell-offs were concentrated in Technology and Consumer Discretionary, down 10.4% and 3.2% respectively, while Utilities was the strongest sector, up 9.3%, and continuing its strong run as a safe haven against inflation. For the first time in 2022 the Materials sector fell, down 4.3%, which is an important development for the Australian market. We discuss further below. In terms of factor leadership, growth surprisingly outperformed value in April. While the Technology sector was week, 'growth' stocks in Consumer and Healthcare sectors traded better. The 'value' factor was also dragged down by the Materials sector which has now started to fall, as mentioned above. While May has started poorly for share markets globally, the hedges in our portfolio have so far protected the fund from any drawdown. The strategy is very well suited for the environment we find ourselves in. In April capital markets pivoted from reflation to deflationary bust as investors started to factor in a recession next year. We saw this play out clearly as commodities and commodity currencies fell sharply, including the Australian dollar. With this, late-cyclical sectors such as resources, which had held up relatively well, joining the rout in growth shares. The catalyst for this shift was a further tightening in financial conditions and lockdowns in China weighing on growth in the world's second largest economy. China historically has acted as a counterweight to growth trends in the west, this was particularly evident coming out of the financial crisis. With low vaccination rates amongst seniors in their community they have resolutely stuck to COVID-zero policies. Rolling lockdowns are weighing on growth and further disrupting supply chains into western markets. This is unlikely to change in the medium term given the virulence of Omicron. With China already in a recession, it is unable to play its typical role of balancing weakness in the west. The other major development last month was the breakdown in US mega-cap technology shares. This group of companies has led the share market higher in recent years. Together they account for one quarter of the value of the S&P 500. Until April they managed to escape the broader weakness in the NASDAQ. The 'Generals' as they are often called, reported disappointing results for Q1 2022, with Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Facebook either missing expectations or providing weak guidance. The NASDAQ and Russell 2000 having fallen more than 20% now, joining emerging market equities and growth sectors in a new bear market. The Australian share market had been resilient through this earlier weakness in shares offshore only to fall sharply as commodities and mining shares broke down with the news out of China and broader concerns of a pending global recession. China almost certainly is already in a recession with growth in business activity and household spending in full retreat. If you break down the Financial Conditions Index (FCI) into asset values (falling); interest rates across the term structure (rising); and the US dollar (rising), FCI is tightening quickly, and we are only just embarking on a tightening cycle. The incidence of central banks tightening to combat inflation is the highest in many decades. This will likely end in recession in advanced economies. As these economies slow, profit expectations for public companies will fall along with valuation multiples as real interest rates continue to move higher. This is what a bear market looks like and we are almost certainly in one. Bear markets don't end until policy reverses course and financial conditions start to ease. We are still early in this tightening cycle, there is a long way to go. Liquidity will tighten further as central banks become sellers of the assets they have accumulated through COVID emergency measures. Bear markets typically last 18 months to 2 years and don't end until the liquidity spigot is turned back on again. Central banks are fully committed to combatting inflation and will not reverse course until inflation comes back into their target range of 2%. There is no central bank 'put option' this time around - falling asset values only helps Central Banks in their crusade to kill excess demand. While we are probably at peak inflation now and Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE) will moderate in the months ahead as we cycle inflated data from last year, any moderation will happen slowly. Key components of the inflation basket - energy, food and shelter will remain under upward pressure for years to come. Labour markets remain acutely tight, employment needs to fall (recession) to reduce pressure on wages. We are in a 'secular' bull market for commodities, resource security and de-carbonisation will ensure ongoing investment in the sector for decades to come. Australia should benefit from this. While activity will slow in Australia, particularly if our major trading partner China is in recession, our economy should prove resilient even if advanced economies move into recession. There is a good chance Australia avoids the recession bullet once again. Having said that, commodities and mining shares are in a 'cyclical' bear along with other risk assets and will fall through the balance of this year. Share markets globally are over sold short term, sentiment is extremely bearish, and positioning is light. Shares should recover in the weeks ahead, an improvement in COVID cases in China would be particularly helpful. Any rally though should be used as an opportunity to reposition into defensive, quality names that will outperform in a slowing economy. Volatility will remain high into the second half of the year as financial conditions tighten further. We are still to see an exodus of retail investors who invested $1.3 trillion globally in equities through COVID. As markets fall in the second half of the year and investors come to realise, there is no central bank bailout this time around, a weaker tape could easily turn into a rout as we close the year. The bear is just getting started. SECTORS IN REVIEW The Consumer sector made a positive contribution for the month, with gains in Fuel marketing longs partially offset by losses on Agriculture shorts. Our long position in the Fuel Marketers has been gaining momentum as fuel security becomes an increasing issue for Western Governments. Ampol (ALD) and Viva Energy (VEA) refining assets, which are generally loathed by the market, are now generating super returns and driving upgrades for both companies. This sector is under-owned and offers defensive exposure at a cheap multiple. While coming at a cost to near-term performance in April, the Agriculture sector is building as fertile ground for short ideas. Share prices have risen aggressively, given the confluence of a strong domestic grain harvest, and sky-high soft commodity prices driven by supply-chain dislocation. We know however, as with all highly cyclical industries, that conditions are ever changing, and we should be careful extrapolating at either the top or the bottom of the cycle. To overcome this issue focus should always be given to mid-cycle analysis. Given decades of data on the Australian grain crop, we can predict with some certainty what mid-cycle earnings for companies like GrainCorp (GNC) might look like. On these mid-cycle earnings, current valuation multiples look extreme. Financials had a disappointing month in April. The primary driver was our long position in EML Payments (EML). EML delivered a guidance downgrade two months after its result in February. Given the volatility in the market, earnings dependability is currently paramount. As such, unexpected downgrades are seeing stocks punished by investors, with EML nearly halving over the month. In March, we saw press coverage that EML was being stalked by Private equity player Bain Capital, this saw the price above $3.00. We are cautiously optimistic that EML is forced to negotiate a reasonable price, which we view as the best outcome for investors. The TMT portfolio was a slight detractor of performance during the month. Our shorts in internet companies delivered as investors focused on deteriorating housing market drivers. They have also been caught up in a broader global technology sell off. Offsetting this was our technology portfolio, where losses were largely driven by our position in Life360 (360). 360 gave a quarterly update, where it reinstated guidance. We viewed the update as overall positive and were surprised to see the share price negatively impacted. We continue to see absolute and relative value in the name. The Mining sector was hit hard in April on lockdowns in China. The best performers recently were impacted the hardest with lithium names in particular retracing recent gains. Commodity prices were also weaker with lithium chemical and rare earths prices falling off peak levels. Coal continued to perform with our investment in Stanmore Resources (SMR) making a strong contribution. Healthcare: The medical device names are struggling with supply chain issues. Notably, ResMed (RMD) has had trouble locating components out of Asia. Industrials: Defensive industrial shares outperformed with Amcor (AMC) and Brambles (BXB) leading. Elsewhere housing names continued to struggle as investors adopted a more bearish view of housing activity and the property market- the building material names in particular were weak. Funds operated by this manager: Watermark Absolute Return Fund, Watermark Australian Leaders Fund, Watermark Market Neutral Fund Ltd (LIC) |

3 Jun 2022 - Decarbonisation - A Risk To Dividends?

|

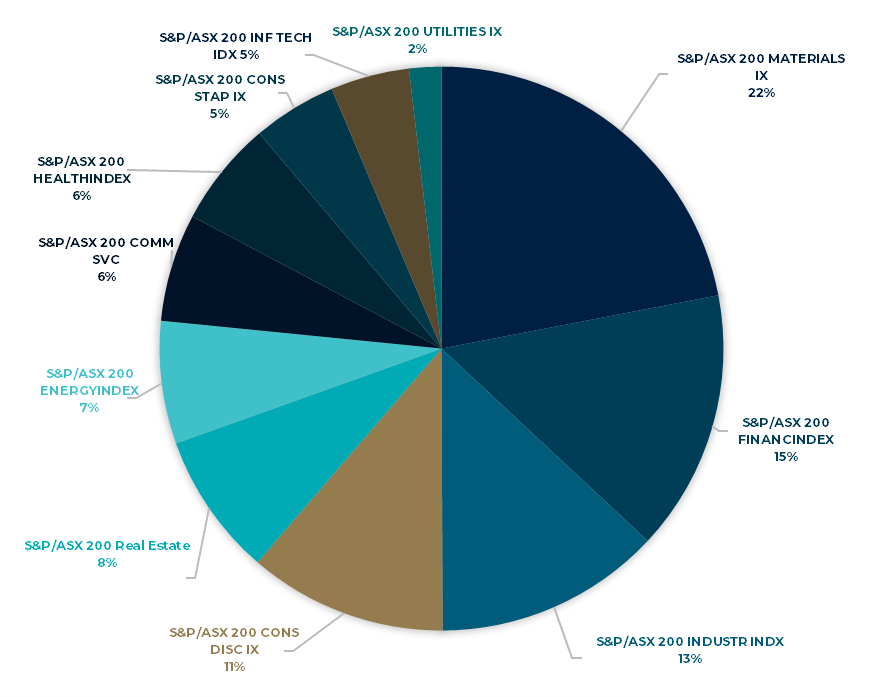

Decarbonisation - A Risk To Dividends? Tyndall Asset Management May 2022 In this article, Michael Maughan, Portfolio Manager of the Tyndall Australian Share Income Fund, discusses the impact on the big dividend payers from decarbonisation and where he sees opportunities for equity income investors. Knowing where a company or industry is in its economic cycle, allows investors the ability to judge when to invest, and when to wait for a cheaper opportunity. This is because companies are subject to different economic cycles. For example, the mining sector aligns more with Chinese growth than the US. Understanding Capex cycles—including the coming decarbonisation cycle—are relevant for dividend-focused investors due to the deployment of cashflows within those companies. Where has the Australian market's dividends come from historically? First, we need to look at which sectors have yielded the highest dividends for investors. Chart 1 shows that 37% of the yield over the past ten years has come from financials and materials. Not surprising given they are the largest sectors in the Australian market but perhaps surprising given mining companies often have a poor record in the capital discipline. That mix has changed over time, and those two sectors made up 56% of the yield in 2021. Chart 1. 10 years of ASX200 dividends

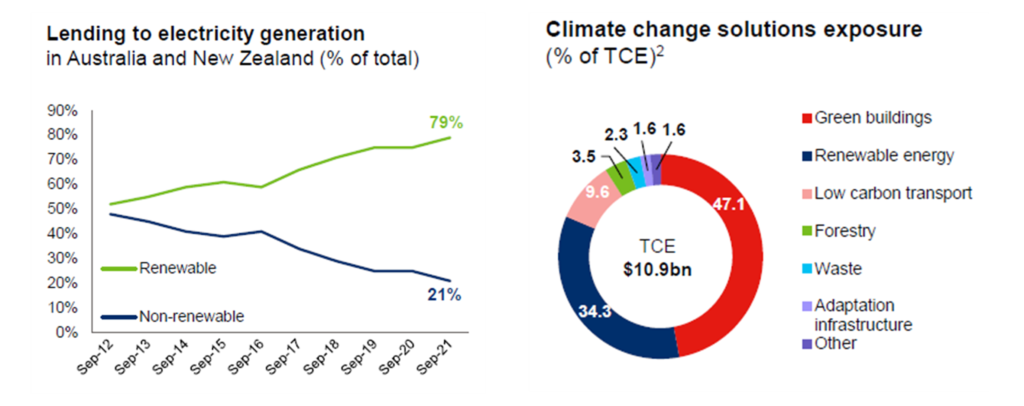

Banks have been consistent in their dividend payments except for a brief hiatus at the peak of COVID uncertainty. Materials have been more volatile with a big step down as China slowed and progressive dividend policies ceased in 2015/16, and a big step up in the past couple of years as commodity prices have boomed. However, going further back, the ability of miners to pay dividends was a function of the CAPEX they were spending and the prevailing commodity prices. Over the past ten years, we have seen this trade-off between dividends and investment in energy names like Oil Search (now part of Santos) and Woodside. Oil Search prioritised LNG projects in PNG over dividend payments, and Woodside had a fluctuating dividend structure depending on its balance between producing assets and its LNG projects in WA. As we discuss later in this piece, this balance could be changing. So how could the energy transition impact big dividend payers' ability to maintain dividends? Decarbonisation is a capex cycle to play out over 20-30 years. Firstly, companies are decarbonising their operations. Secondly, globally we need to spend trillions of dollars on new nickel, lithium, copper, and cobalt mines to renewably electrify the world. While this doesn't sound great for dividends, the market has already factored much of this in. BHP and RIO Tinto have been explicit about the investments they are making to decarbonise their operations. BHP will increase capex by U$200 million p.a, for the next five years, and RIO Tinto will spend an extra U$500 million p.a. over the next three years. The majority of this will go to renewable power generation in the Pilbara. Therefore, if there are extra costs of decarbonising operations (that may or may not be recovered in premium pricing), there is the capex opportunity to meet the demand created by the need for additional wires and batteries. Copper demand could double, and nickel demand could quadruple to meet Paris targets through ongoing electrification. Net-net, this is a positive story for the diversified miners. Having growth opportunities to invest in that will generate cash and dividends in the future is much better than being a declining business with a high payout ratio. Share prices never assumed this level of cash flow was forever. The banks have an opportunity to fund renewable projects through lending discussed by Brad Potter, Tyndall's Head of Australian Equities, in his article: Banks funding renewables set to drive growth. Chart 2. shows that Westpac has been skewing away from fossil fuels towards renewables for 10 years already. Whether the Australian banks will be able to compete with the global interest to lend to these projects is unknown, but it is more opportunity than risk. Chart 2. Westpac's electricity generation lending over time and climate change solutions exposure Source: The Westpac Group Can dividends benefit from decarbonisation over the coming decades? In the medium term, we expect that the traditional energy companies will be investing less capex, and concentrating on harvesting their current assets to facilitate the energy transition, meaning more cash being returned to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. The mergers of Oil Search with Santos and Woodside with BHP petroleum create more balanced businesses with pristine balance sheets, strong cash flows, and a higher percentage of producing assets to fund growth opportunities or return cash to shareholders. Interestingly, Macquarie is aggressively pursuing growth in both renewables and electricity infrastructure and have a model that develops assets on the balance sheet and then sells them down into funds in the same way the Goodman Group does for industrial property. This focus has received a lot of attention and has been part of the stock's rerating. However, they also have one of the world's biggest energy trading businesses and therefore have been huge beneficiaries of the volatility in traditional energy markets. The holy grail is a company that is exposed to the energy transition without necessarily being as capital intensive as a miner. One of the issues with the growth in renewables is that the transmission networks are not built for this decentralised generation structure. We have lots of small producers, batteries that need electricity going in and out, and even household solar has changed the nature of the grid. The result is that Australia need to add 10km of transmission lines to the existing 45km but current capacity to roll out is only 700m pa. Downer Group is in a prime position to capitalize on this as highlighted in chart 3 as a leading player in electrical engineering and construction with 70 years' experience. Worley is also growing the part of their business that consults with the hydrogen industry, although their core fossil fuels business has associated downside risks. Chart 3. Downer capabilities leveraged to decarbonization

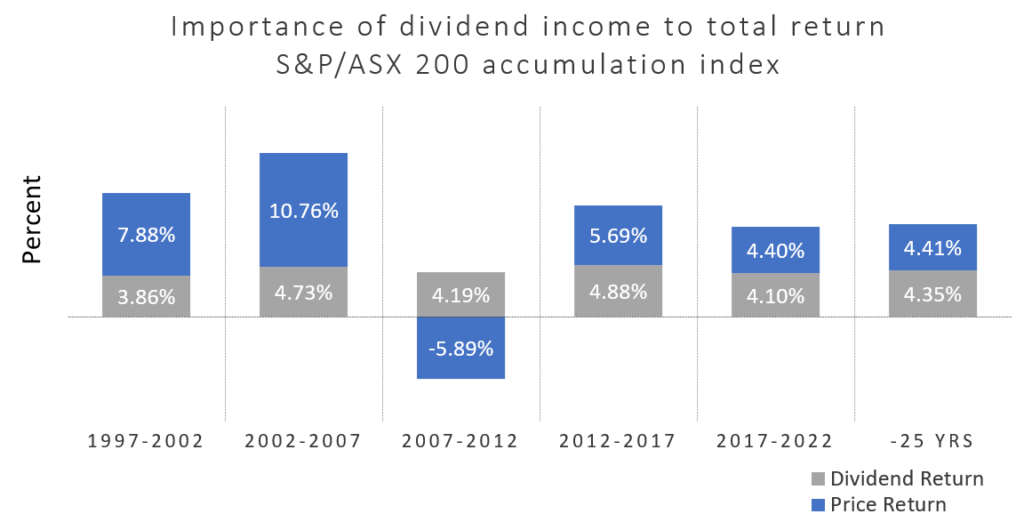

Source: Downer Group Conclusion While we see a peak in capital returns from miners due to unprecedented supply/demand imbalances and low CAPEX pipelines, the expected increased investment in decarbonisation programs is unlikely to wipe out the traditionally high yield of the Australian equity market. The tax structure still incentivises Australian companies to pay franked dividends, and the index composition is skewed to cash-generating companies. Over decades the Australian market has delivered net yields in the 4% range as shown in Chart 4 (5%+ grossed up for franking), and we don't expect that to change materially in the future.

Chart 4. The importance of dividend income to total return Source: S&P/ASX; IRESS; Sub-periods are rolling five-years to illustrate consistency of income Author: Michael Maughan, Portfolio Manager, Tyndall Australian Share Income Fund Funds operated by this manager: Tyndall Australian Share Concentrated Fund, Tyndall Australian Share Income Fund, Tyndall Australian Share Wholesale Fund Important information: This material was prepared and is issued by Yarra Capital Management Limited (formerly Nikko AM Limited) ABN 99 003 376 252 AFSL No: 237563 (YCML). The information contained in this material is of a general nature only and does not constitute personal advice, nor does it constitute an offer of any financial product. It does not take into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of any individual. For this reason, you should, before acting on this material, consider the appropriateness of the material, having regard to your objectives, financial situation, and needs. The information in this material has been prepared from what is considered to be reliable information, but the accuracy and integrity of the information is not guaranteed. Figures, charts, opinions and other data, including statistics, in this material are current as at the date of publication, unless stated otherwise. The graphs and figures contained in this material include either past or backdated data, and make no promise of future investment returns. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. Any economic or market forecasts are not guaranteed. Any references to particular securities or sectors are for illustrative purposes only and are as at the date of publication of this material. This is not a recommendation in relation to any named securities or sectors and no warranty or guarantee is provided. |

2 Jun 2022 - Sustainable earnings growth over multiple cycles

|

Sustainable earnings growth over multiple cycles Insync Fund Managers May 2022 Markets tend to wrong-foot many investors, regardless of investment style, with 2022 becoming a year of extremes. Central banks are dealing with the prospect of stagflation, an environment that bankers do not have experience in, as this last occurred in the early 70's. Investors trading with a short-term time horizon have rushed into expensive defensive plays boosting their price further such as utilities, consumer staples and energy. They're attempting a 'momentum play'. To succeed, their timing will need to be impeccable at both ends. Later on, we will explain by example why this is contradictory to common sense and how you can avoid this risk. History consistently shows that investing on the basis of the short term economic outlook leads to poor outcomes. In 2021 the consensus was that 22' will be a period of reasonable economic growth and low inflation. That narrative changed quickly to a year where inflation is rising and concerns over recession looms. It is very likely that consensus will be wrong again. Insync's focus is always on longer term outcomes. Thus, we invest only in businesses that have the capacity to generate sustainable earnings growth through the cycle and over multiple cycles. Whilst recent fund returns have been disappointing, the businesses in our portfolio continue to deliver strong growth in their revenues and their profits despite the current market backdrop. The consistently longer term strong share price rises of highly profitable growth companies like these, over many decades, supports this approach to investing. In last month's edition we showed how stock prices over time tracks to this result. For now, the Insync portfolio is trading at a discount well in excess of 50% of our proprietary based DCF methodology. As an investor this is worth reflecting upon: after the pull back in the markets of some of the most profitable secular growth companies in our portfolio that typically trade on higher P/Es, they are now perversely trading on much lower P/Es, as markets presently ignore their superior financial metrics and earnings power! This will not continue beyond the short term as we explain later on. We strongly believe that for long-term investors, quality growth stocks are now available at bargain prices.

Short-Lived Disconnects (reality V price) Investors have flocked into defensive sectors to hide in the short-term. Fears of markets falling further has resulted in quality growth stocks becoming attractively valued. In times of volatility, investors are presented with an outstanding opportunity to invest in these enduring businesses.

Here is a real example today of investors losing sight of business realities versus current prices.

Company A - A well-known technology company. It's recently been aggressively sold down. Yet it's continuing to be one of the most profitable global businesses, with over 90% market share and compounding revenues at 20+% p.a. for the past 5 years. Despite this investors are attributing a low price to earnings ratio to the business. Company B - The leading soft drinks company. One which investors have flocked to for safety in the current market clime. It's significantly less profitable than Company A. Revenue growth has been negative over the past 5 years with total revenues today sitting at -19% below 10 years ago in 2012. Despite poor operating performance with no revenue growth for 10 years and no prospects of such, investors are attributing a high price to earnings ratio to the business. Which would you own?

A quirk of markets today that is worth knowing For now, most investors have flocked to industries and businesses that resemble Company B. Go figure? Interestingly many of the sectors that capital is pouring into since February - and pushing up their prices will likely suffer far more financially than those like Company A and its industry; especially if the dire economic forecasts for the years ahead come true. Again, go figure? By now you would have worked out that Company A is Alphabet and Company B is Coca-Cola. Clearly there is today a temporary disconnect between fundamentals and share prices! Over the long term the share price of a company follows its earnings growth. Broad indiscriminate market corrections often provide investors a once in a cycle opportunity to invest in the most profitable companies such as Alphabet. This will set them up nicely to achieve strong returns in the future. How price follows earnings once again

Whilst short term volatility may persist, Insync's concentrated portfolio of quality stocks across 16 global megatrends is well positioned to perform strongly over the long term. Why? The consistent strong earnings growth these companies are set to deliver should result in much higher share prices over time once markets adjust after the initial shift- as they always do. Whilst headlines and prices across all tech stocks have been hit hard, only some deserved it. Markets don't care initially; they just treat all growth stocks the same, quality or not. Only after this period is over the market separates the wheat from the chaff. This table highlights examples of those probably deserving of such a negative move. It depicts their price declines from their all-time recent highs. None of these companies exhibit the financial abilities we at Insync require.

Funds operated by this manager: Insync Global Capital Aware Fund, Insync Global Quality Equity Fund Disclaimer |