NEWS

1 Sep 2022 - Quay Global Podcast - Investment Perspectives: 12 charts we're thinking about right now

|

Quay Global Podcast - Investment Perspectives: 12 charts we're thinking about right now Quay Global Investors August 2022 |

|

Chris Bedingfield speaks with Holly Old about the team's latest - and highly popular - Investment Perspectives article, 12 charts we're thinking about right now.

Speakers: Chris Bedingfield, Principal and Joint Managing Director

|

|

Funds operated by this manager: The content contained in this audio represents the opinions of the speakers. The speakers may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the audio. This commentary in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the speakers to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the listener. |

31 Aug 2022 - Market volatility creates opportunities

|

Market volatility creates opportunities L1 Capital August 2022 WEBINAR REPLAY | L1 Capital International Fund | August 25, 2022 David Steinthal, CIO of L1 Capital International, provides an update on the positioning of the L1 Capital International Fund and key takeaways from recent results season. • Investment environment (0.45) • Performance and Portfolio recap (4.26) • Results season - Key takeaways (9.12) • Summary (23.13) • Q&A (24.17) Funds operated by this manager: L1 Capital Long Short Fund (Monthly Class), L1 Capital International Fund, L1 Capital Long Short Fund (Daily Class), L1 Long Short Fund Limited (ASX: LSF), L1 Capital Catalyst Fund, L1 Capital Global Opportunities Fund |

30 Aug 2022 - Outlook Snapshot

|

Outlook Snapshot Cyan Investment Management July-August 2022 |

|

Outlook |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Cyan C3G Fund |

30 Aug 2022 - Nuclear energy is a promising solution for climate change

|

Nuclear energy is a promising solution for climate change Magellan Asset Management August 2022 |

|

Fukushima, on the northeast of Japan's largest island, is vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis. From 1971, the area hosted the Daiichi nuclear plant. Based on global appraisals of tsunamis, the facility was built 10 metres above sea level. The commercial plant and others ensured nuclear energy supplied 30% of Japan's power needs.[1] That is until an earthquake of magnitude 9.0 on the Richter scale struck in 2011. An ocean surge, which peaked offshore at 23 metres, was still 15 metres high when it swamped three reactors at the Daiichi plant. Radioactive material escaped for six days. More than 2,300 people died and over 100,000 were evacuated.[2] Japan was paralysed by what the chairman of a parliamentary inquiry described as "a profoundly man-made disaster".[3] Tokyo reacted to the alarm of a public who watched on TV as the tsunami smashed into land. Within a year, only one of Japan's 54 nuclear reactors was operating. Enthusiasm for nuclear power, which reached a peak of 17% of global energy production in 1996,[4] dimmed around the world.[5] Germany immediately decided to phase out its 17 nuclear plants by 2022. Only three remain but it looks like Europe's energy crisis could delay their closure. In the rest of Europe, the drive to nuclear power stalled such that Italy, Lithuania and nearby Kazakhstan have ditched nuclear while Finland in March opened the continent's first new nuclear plant in 15 years. The US has opened only one reactor (in 2016) since 1996. Reduce one risk but still face another. That danger is climate change. The UN-overseen Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned in April the world is "at a crossroads" in its quest to halve emissions by 2030 to limit the rise in the earth's temperature.[6] The obstacles? Voters oppose carbon taxes. Renewable energy is struggling to match fossil fuels as a source of 'baseload' power on reliability and cost. Declining investment in fossil fuels has boosted hydrocarbon prices. Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February further bolstered oil and gas prices while exposing Europe's reliance on Russian energy as a liability. 'Energy security' has gained renewed political significance. What to do? A large part of the answer could be nuclear energy, which is generated in a process known as fission - when uranium or plutonium atoms are split to release heat that makes steam to spin turbines.[7] Even though radioactive waste is produced during fission that can last forever,[8] policymakers are talking of adding to the 439 reactors in operation across 32 countries (while another 54 reactors are being built) that still supply about 10% of the world's energy needs.[9] The talk is generating action. The US in April announced a US$6 billion effort to prevent more closures among the country's 94 reactors sprinkled across 56 plants that make the US the world's largest generator of nuclear power. Since 2013, 12 US reactors have closed 'early' and another 11 reactors are scheduled to shut by 2025.[10] Nuclear power, first tapped in the US in 1958, has supplied about 20% of US electricity generation since 1990.[11] Europe too is reemphasising nuclear. The UK in April said it would build as many as eight new nuclear plants by 2030.[12] In February before Ukraine was invaded, French President Emmanuel Macron said the world's second-most nuclear-powered country (56 reactors that supply 70% of the country's electricity) needed 14 new reactors by 2050.[13] Earlier the same month, the European Commission added nuclear energy to a list of sustainable energy sources that are valid replacements for fossil fuels.[14] In July, the European Parliament backed the EC decision.[15] Asia hosted all the world's new nuclear capacity in 2021 and more is coming.[16] It's easy to see why leaders are attracted to nuclear energy. As long as countries can source uranium or plutonium, the nuclear option offers energy self-sufficiency and is the lowest-cost greenhouse-gas-free energy - one that is cheaper than all but the lowest-cost fossil fuels. OECD analysis, which assumes long-lasting nuclear plants will spread fixed costs and adds a carbon price of US$30 per tonne of CO2 onto the cost of fossil fuels, estimates nuclear energy could cost as little as US$30 a megawatt hour compared with US$45 for gas and US$75 for coal.[17] Two promising developments could make nuclear more appealing. The first is the coming of commercial mini-nuclear reactors.[18] These mini-reactors would produce between 300 megawatts (small) and 700 megawatts (medium) of power compared with at least 1,000 MW electrical (MWe) produced by standard-sized reactors. The advantages of mini-reactors are lower initial capital costs, less-complex design and that they take only four years to build rather than the decade needed for standard facilities. Mini-reactors can be built and shipped, thus are a better option for remote areas. They are safer because they require no manpower or electricity to shut down.[19] They produce less waste. They are cheaper to decommission. The International Atomic Energy Agency says there are about 50 designs for mini-reactors and four are close to being finished in Argentina, China and Russia.[20] Rolls-Royce says it can have 470 MWe mini-reactors connected to the UK grid by 2029.[21] The second development is nuclear fusion. Whereas in nuclear fission an atom is split, fusion is combining atoms (using special hydrogen, deuterium and tritium as fuel). When fusion occurs, the difference in mass between nuclei and the newly formed heavier-but-lower-mass atom is released as energy. It takes special machines (tokamaks) or lasers to generate the intense heat and powerful magnetic forces required to produce an energy so powerful that one litre of fusion fuel matches 55,000 barrels of oil for energy.[22] Breakthroughs are occurring in mimicking the energy source of the Sun and stars. In the UK in February, a fusion reactor produced a world record of 59 megajoules of heat energy over five seconds, more than double the previous record of 22 megajoules set in 1997.[23] In the US last September, a superconducting magnet needed in fusion broke magnetic field strength records during trials.[24] A month earlier in the US, laser light created enough heat to generate a record yield of laser fusion; 10 quadrillion watts of fusion power for 100 trillionths of a second.[25] Aside from producing greenhouse-gas-free energy, fusion comes with two other notable advantages. One is that fusion eradicates the risk of a nuclear meltdown because, if disturbed, the process stops. The other is that no radioactive waste is produced. Fusion research is expensive, however, and advances whereby fusion reactors offer the world affordable power seem far off and might never happen. That's the best hope too for the devastation that nuclear energy risks. Accidents that include Three Mile Island in the US in 1979, Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union in 1986 and Fukushima are blamed on human error. A possible calamity occurred in March when Russian shelling started a fire at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant in Ukraine, which with six reactors is Europe's largest. The incident highlighted the vulnerability of nuclear facilities to war, terrorism, suicidal rage or rogue states turning a nuclear plant into a military base, as Russia has now done with Zaporizhzhia.[26] Many say ageing nuclear facilities pose a threat. Nearby Germans have long had concerns about the state of the Tihange nuclear plant in Belgium. The regional German government has called for the plant to be closed.[27] Nuclear energy's risk tied to the internet age is cybersecurity. The US and Israel in 2010 used Stuxnet malware to interfere with Iran's Natanz plant while a nuclear plant in Germany was reported to have suffered a "disruptive" cyberattack about a decade ago.[28] While the threat might be exaggerated by opponents of nuclear energy, it adds to political challenges of gaining public support for the nuclear option.[29] Even with all the risks, nuclear energy is an established source of power that will gain traction as an answer for climate change, especially if more technological leaps are made. Nuclear energy might be most notable for how its adoption will vary across countries as communities judge their tolerance for the risks surrounding the most-promising energy solution to mitigate global warming. To be sure, nuclear is not touted as the sole solution for climate change. Leaps in renewable technology or its economics could undermine the need for nuclear. But the reverse could apply too. The shift to more nuclear could take too long to contain the rise in the earth's temperature to 2 degrees Celsius. Nuclear energy, with its huge initial investment, might never match the lowest-cost fossil fuels, especially if plants are excessively regulated to soothe public concerns about safety. Some countries such as Australia and Germany are against nuclear though the energy crisis could change that.[30] Russia exports nuclear technology so its isolation might slow the industry's development. Any nuclear-building spree comes with risks and no doubt cost overruns (a problem too when upgrading ageing facilities). Against this, only three notable accidents in more than six decades is a fair safety record for any industry. Energy security is what gives nuclear energy fresh appeal. Expect more policymakers to push for nuclear. It's just that the next nuclear mishap - and human error, even malevolence, almost guarantees one - might, Fukushima-style, set back the best option to mitigate climate change on every measure but safety. Heavier but less mass Tokamak is a Russian acronym that stands for the 'toroidal chamber with magnetic coils' that was developed in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s. The machine contains a large doughnut-shaped vacuum chamber where a few grams of hydrogen fuel are heated to 150 million degrees Celsius to form a substance known as plasma. This substance allows electrons to roam between different nuclei so they can collide and fuse. The challenges include having sufficient plasma particle density to increase the likelihood that collisions occur and enough confinement time to hold the plasma, which has a propensity to expand, within a defined volume. Within the tokamak, magnetic fields are used to confine and control the plasma.[31] The process is seeking to capitalise on the insights of UK physicist Arthur Eddington (1882-1944).[32] Eddington observed that four hydrogen atoms weigh more than one helium atom. He surmised that if four hydrogen nuclei were fused then some mass must be lost in the process. According to Einstein's famous equation E=MC2, that lost mass must become energy that amounts to the mass lost multiplied by the speed of light. Eddington's brilliance, as revealed in his book Internal constitution of the stars in 1925, was he deduced that hydrogen crashing into hydrogen to form helium under immense gravitational forces is how the Sun and stars produce energy (shine).[33] The hope of many scientists nowadays is that nuclear fusion is the solution to climate change, even the world's energy needs. Many have tried since the explosion of a hydrogen bomb in 1952 to crack nuclear fusion as a source of power. The world's biggest experiment underway to achieve nuclear fusion is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, or ITER, Project that groups China, the EU, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the US. ITER's first plasma experiment is scheduled for 2025, 15 years after building the facilities began on a site in the south of France. With 10 times the plasma volume of the largest machine operating now, the ITER tokamak is designed to move on from small-scale fusion experiments. The key quest is to get fusion to reach the point where the energy output from the fusion reaction matches the energy needed to create the conditions that sustain the fusion reaction. A later goal of ITER is to attain 10 times the energy output, which would mean that 50 megawatts of heating power could become 500 megawatts of fusion power.[34] If scientists at ITER or elsewhere achieve these and other feats, nuclear fusion could well power the world. No breakthroughs away from ITER appear imminent while the ITER results won't be known for decades and might prove fruitless. In the meantime, nuclear fission conducted in mini-reactors might be the best option for those countries willing to risk using nuclear power to combat climate change. Number of nuclear reactors by country Author: Michael Collins, Investment Specialist |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund [1] World Nuclear Association. 'Fukushima Daiichi disaster.' Updated April 2021. world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident.aspx [2] The earthquake and tsunami are estimated to have killed nearly 20,000 people. [3] The National Diet of Japan. 'Official report of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission.' 2012. Chairman Kiyoshi Kurokawa. Page 9. web.archive.org/web/20120710075620/http://naiic.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/NAIIC_report_lo_res.pdf [4] Britannica. 'Nuclear power.' britannica.com/technology/nuclear-power. See also International Atomic Energy Agency. 'Nuclear power status in 1996.' 24 April 1997. iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/nuclear-power-status-1996 [5] See Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. 'Nuclear power and the public.' 3 August 2011. thebulletin.org/2011/08/nuclear-power-and-the-public/ t [6] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth assessment report. Media release. 'The evidence is clear: The time for action is now. We can halve emissions by 2030.' 4 April 2022. ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/resources/press/press-release/ [7] See 'Nuclear 101: How does a nuclear reactor work?' US Department of Energy. 29 March 2021. energy.gov/ne/articles/nuclear-101-how-does-nuclear-reactor-work [8] Plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,000 years while strontium-90 and cesium-137 have half-lives of about 30 years (half the radioactivity will decay in 30 years). See US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Last reviewed 23 July 2019. nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/radwaste.html [9] IAEA. 'The database on nuclear power reactors.' World statistics. These reactors amount to 393,818 megawatt electrical total net installed capacity, while those being built promise 53,744 MWe more capacity. In Asia, countries building reactors are China (16 under construction), India (six), Japan (two to add to 33 operational reactors), and Korea (four). Two more countries are poised to host nuclear power when the plants under construction are built. Last updated 18 July 2022. pris.iaea.org/pris/ [10] US Department of Energy. 'DOE seeks applications, bids of $6 billion civil nuclear credit program.' 19 April 2022. energy.gov/articles/doe-seeks-applications-bids-6-billion-civil-nuclear-credit-program [11] US Energy Information Administration. 'Nuclear explained. US nuclear industry.' Last updated 21 April 2021. Figures are for the end of 2020. eia.gov/energyexplained/nuclear/us-nuclear-industry.php [12] BBC. 'Energy strategy: UK plans eight new nuclear reactors to boost production.' 7 April 2022. bbc.com/news/business-61010605. See UK government. 'Nuclear energy: What you need to know.' 6 April 2022. gov.uk/government/news/nuclear-energy-what-you-need-to-know [13] France 24 news services hosting article by Agence France-Presse. 'Macron calls for 14 new reactors in nuclear 'renaissance'. 10 February 2022. france24.com/en/live-news/20220210-macron-calls-for-14-new-reactors-in-nuclear-renaissance [14] European Commission. 'EU Taxonomy: Commission presents Complementary Climate Delegated Act to accelerate decarbonisation.' 2 February 2022. ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_711 [15] European Parliament. 'Taxonomy: MEPs do not object to inclusion of gas and nuclear activities.' 6 July 2022. europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220701IPR34365/taxonomy-meps-do-not-object-to-inclusion-of-gas-and-nuclear-activities [16] IAEA. 'Nuclear power reactors in the world.' 2022 edition. pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/RDS-2-42_web.pdf. Page 2. [17] Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development with the International Energy Agency and the Nuclear Energy Agency. 'Projected costs of generating electricity 2020 edition.' Page 14. oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-12/egc-2020_2020-12-09_18-26-46_781.pdf. See World Nuclear Org. 'Economics of nuclear power.' Updated September 2021. world-nuclear.org/information-library/economic-aspects/economics-of-nuclear-power.aspx [18] The US military first used smaller reactors in 1962. World-nuclear.org. 'Small nuclear power reactors.' Updated December 2022. world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-power-reactors/small-nuclear-power-reactors.aspx [19] TIME. 'As Putin threatens nuclear disaster, Europe learns to embrace nuclear energy again.' 22 April 2022. time.com/6169164/ukraine-nuclear-energy-europe/. See 'Table 1. Safety enhancement and cost reduction benefit-challenges analysis.' Page 16. International Atomic Energy Agency TECDOC series. 'Benefits and challenges of small modular fast reactors.' 2021. pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TE-1972web.pdf [20] International Atomic Energy Agency. 'Small modular reactors.' iaea.org/topics/small-modular-reactors [21] 'Green light for mini-nuclear reactors by 2024, says Rolls-Royce.' The Telegraph of the UK. 19 April 2021. telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/04/19/green-light-mini-nuclear-reactors-2024-says-rolls-royce/ [22] Bloomberg News. 'Nuclear fusion could rescue the plant from climate catastrophe.' 29 September 2019. bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-09-28/startups-take-aim-at-nuclear-fusion-energy-s-biggest-challenge. For the same mass of material, fusion produces four times more energy than fission. International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, or ITER, Project. 'Advantages of fusion.' Undated. iter.org/sci/Fusion [23] ITER Newsline. JET makes history, again.' 14 February 2022. org/newsline/-/3722 [24] Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 'MIT-designed project achieves major advance towards fusion energy.' 8 September 2021. news.mit.edu/2021/MIT-CFS-major-advance-toward-fusion-energy-0908 [25] National Ignition Facility. 'National Ignition Facility experiment puts researchers at threshold of fusion ignition.' 18 August 2021. llnl.gov/news/national-ignition-facility-experiment-puts-researchers-threshold-fusion-ignition [26] 'Russia's army turns Ukraine's largest nuclear plant into a military base.' The Wall Street Journal. 5 July 2022. wsj.com/articles/russian-army-turns-ukraines-largest-nuclear-plant-into-a-military-base-11657035694 [27] John Kampfner. 'Why Germans do it better.' Atlantic Books. Paperback edition 2021. Pages 252 to 253. [28] Infosec. 'Cyberattacks against nuclear plants: A disconcerting threat.' 14 October 2016. resources.infosecinstitute.com/topic/cyber-attacks-against-nuclear-plants-a-disconcerting-threat/ [29] Public opposition to waste solutions is always a hurdle. See 'The nuclear power dilemma: Where to put the lethal waste.' The big read. The Financial Times. 6 February 2022. ft.com/content/246dad82-c107-4886-9be2-e3b3c4c4f315 [30] See 'Why Germany is resisting calls to ease energy crunch by restarting nuclear power.' 20 April 2022. Germany along with Austria, Denmark, Luxemburg and Portugal even opposed the EU adding nuclear to the taxonomy. ft.com/content/229c21c7-991c-4b44-a2f9-20991670a4ba [31] ITER Project. 'What is fusion?' and 'What is a tokamak?' sections. iter.org/proj/inafewlines#3 [32] Britannica. 'Arthur Eddington, British scientist.' britannica.com/biography/Arthur-Eddington [33] Rivka Galchen. 'Can nuclear fusion put the brakes on climate change?' The New Yorker. 4 October 2021. newyorker.com/magazine/2021/10/11/can-nuclear-fusion-put-the-brakes-on-climate-change [34] Daniel Andruczuyk, associate research professor, nuclear, plasma and radiological engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. 'Will nuclear fusion ever power the world?' 28 December 2021. gizmodo.com/will-nuclear-fusion-ever-power-the-world-1848149991. Important Information: This material has been delivered to you by Magellan Asset Management Limited ABN 31 120 593 946 AFS Licence No. 304 301 ('Magellan') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should read and consider any relevant offer documentation applicable to any investment product or service and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making any investment decision. A copy of the relevant PDS relating to a Magellan financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4888 or by visiting www.magellangroup.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any strategy, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to be implemented and its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of a Magellan financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Magellan makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Magellan. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any trademarks, logos, and service marks contained herein may be the registered and unregistered trademarks of their respective owners. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan. |

29 Aug 2022 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Ausbil Australian Geared Equity Fund | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Ausbil Australian Emerging Leaders Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Ausbil Balanced Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Candriam Sustainable Global Equity Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Fortlake Sigma Opportunities Fund | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Fortlake Real-Income Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Fortlake Real-Higher Income Fund |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 700 others |

29 Aug 2022 - Global equities strengthen

|

Global equities strengthen Glenmore Asset Management August 2022 After a very challenging finish to FY22, July was a strong month for equities globally. In the US, the S&P 500 rose +9.1%, the Nasdaq was up +12.4%, whilst in the UK, the FTSE was more muted, rising +3.5%. Domestically, the ASX All Ordinaries Accumulation Index rose +6.3%. The top performing sectors on the ASX were technology (assisted by falling bond yields), whilst resources were the worst performer, driven by weaker commodity prices. Unsurprisingly, small caps outperformed large caps as investor risk appetite materially improved. In our view the key driver of the rally in July was investor expectations around inflation (and hence interest rate hikes) beginning to moderate as commodity prices eased, and with central banks now well underway with raising rates, investors potentially can see some light at the end of the tunnel with regards to the current restrictive monetary policy. During the month, the Federal Reserve (US central bank) increased the Fed Funds Rate by 75 basis points (bp) to a range of 2.25% - 2.50%, whilst the RBA increased the cash rate by 50bp to 1.35%. Whilst these are quite material increases, they were largely expected by investors, with consensus that there will be more such hikes over the course of 2022. Commodity prices were broadly weaker in July, driven by fears around an economic slowdown, particularly in China. Iron ore, crude oil and copper all fell -4%, whilst gold declined -2%. Thermal coal outperformed, rising +6%. In the bond market, notably the key US 10 year bond yield fell -36 basis points (bp) to close at 2.70%, whilst the Australian 10 year bond yield fell 60 bp to close at 3.1%. The movements of both in July were a function of some early signs that inflationary pressures have started to ease. Some key themes we will be monitoring are cost pressures and how companies are dealing with them, as well as any impact on demand and/or revenue from recent central bank interest rate increases. As has been the case in the previous years, we are optimistic that reporting season can provide some excellent new investment ideas. Funds operated by this manager: |

29 Aug 2022 - 'Small Talk' - Where have all the IPOs gone?

|

'Small Talk' - Where have all the IPOs gone? Equitable Investors August 2022 In this Small Talk update, we show a chart which highlights IPO activity...or lack of it. IPOs in Australasia are down 88% so far in calendar 2022, relative to the same point in time in 2021, as measured in US dollars raised. That's slightly worse than the global decline of 74%, as per data from Dealogic. The ASX's current list of upcoming IPOs features 10 with an expected listing date, of which only one is not a miner/explorer. Funds operated by this manager: Equitable Investors Dragonfly Fund Disclaimer Nothing in this blog constitutes investment advice - or advice in any other field. Neither the information, commentary or any opinion contained in this blog constitutes a solicitation or offer by Equitable Investors Pty Ltd (Equitable Investors) or its affiliates to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. Nor shall any such security be offered or sold to any person in any jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation, purchase, or sale would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. The content of this blog should not be relied upon in making investment decisions.Any decisions based on information contained on this blog are the sole responsibility of the visitor. In exchange for using this blog, the visitor agree to indemnify Equitable Investors and hold Equitable Investors, its officers, directors, employees, affiliates, agents, licensors and suppliers harmless against any and all claims, losses, liability, costs and expenses (including but not limited to legal fees) arising from your use of this blog, from your violation of these Terms or from any decisions that the visitor makes based on such information. This blog is for information purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice. The information on this blog does not constitute a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Although this material is based upon information that Equitable Investors considers reliable and endeavours to keep current, Equitable Investors does not assure that this material is accurate, current or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Any opinions expressed on this blog may change as subsequent conditions vary. Equitable Investors does not warrant, either expressly or implied, the accuracy or completeness of the information, text, graphics, links or other items contained on this blog and does not warrant that the functions contained in this blog will be uninterrupted or error-free, that defects will be corrected, or that the blog will be free of viruses or other harmful components.Equitable Investors expressly disclaims all liability for errors and omissions in the materials on this blog and for the use or interpretation by others of information contained on the blog |

26 Aug 2022 - Could the US Supreme Court's decision against the EPA derail decarbonisation efforts?

|

Could the US Supreme Court's decision against the EPA derail decarbonisation efforts? 4D Infrastructure August 2022 On 30 June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled in favour of West Virginia and a group of other states in their lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), potentially limiting the agency's ability to enforce actions to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

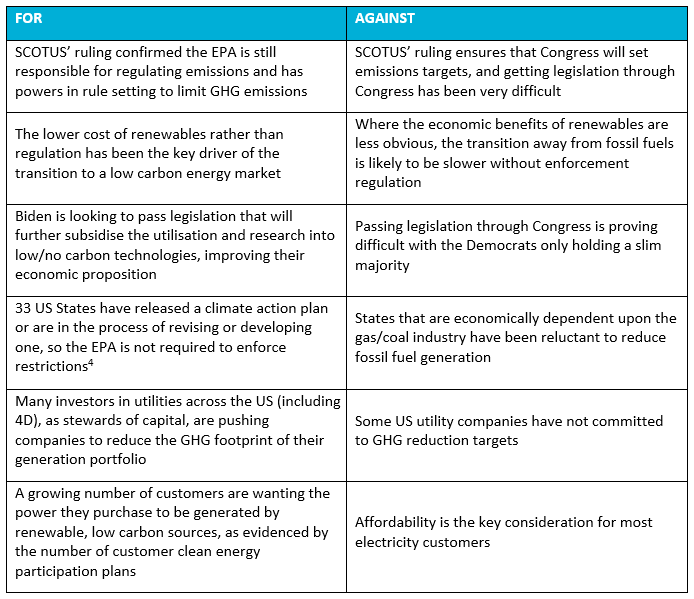

In a majority vote of 6-3, where all six conservative judges sided against the EPA, SCOTUS ruled that the agency overstepped its authority and required 'clear congressional authorisation' to enforce switching from fossil fuel generation to low/no carbon energy. Until now, the EPA had relied on powers provided under the Clean Air Act (1970) in regulating and restricting certain types and volumes of GHG emissions from fossil fuel generation facilities. In this article, we consider what this ruling means for decarbonisation efforts in the US, and for us as global infrastructure investors. Ramifications of the rulingIn its ruling, SCOTUS relied on the 'major questions' doctrine; an academic term the Court used in a ruling for the first time. The doctrine allows judges to strike down regulations or agency actions that 'address questions of vast economic or political significance' without explicit authorisation from Congress[1]. The ruling raises legal questions about the ongoing authority and powers available to the EPA in regulating emissions, and, specifically, what constitutes 'major' - in short increasing legal uncertainty[2]. Some observers have questioned whether the US' commitments to decarbonisation, and specifically the Paris Agreement, can be achieved with the current uncertainty around the EPA's ability to enforce emissions reductions. And if the US is unlikely to achieve its commitments to the Paris Agreement, does that put global efforts to achieve net-zero and limit global temperature increases to well below two degrees Celsius at risk?[3] Does this impede the US' Paris Agreement commitments?Under President Biden, the US made commitments to achieve net-zero by 2050, and reduce GHG by 50% to 52% below 2005 levels by 2030. In light of the SCOTUS ruling, arguments for and against the US' ability to achieve these targets are summarised in the table below.

4D's internal viewThere's no doubt SCOTUS' decision raises questions as to the EPA's ongoing effectiveness in enforcing emissions reductions. This could see some fossil fuel generation facilities, which would otherwise be decommissioned or retrofitted with technology to reduce emissions (such as carbon capture), continue to operate and emit GHGs for longer. This is more likely in states that are economically dependent on the fossil fuel industry. Importantly, however, the US' interim 2030 commitment under the Paris Agreement is more dependent upon the economic benefit argument in transitioning coal generation to renewables, combined with batteries and/or peaking natural gas generation. These economic benefits are supported by technological improvement in low/no carbon technologies and tax subsidies which are currently in place. Biden has communicated the ambition to improve and/or extend these subsidies as part of proposed legislation, which will improve the economics of the transition. Either on their own, or because of investor activism, most US utilities have set GHG reduction targets for 2030 that are in-line with, or more aggressive than, the US' economy wide targets. This improves our confidence that despite SCOTUS' ruling, the US can still achieve its interim commitment under the Paris Agreement. Net-zero still provides a real, long-term investment opportunityWhile the speed of ultimate decarbonisation may remain unclear, as infrastructure investors, we continue to see a real opportunity for multi-decade investment as every country moves towards a cleaner environment. At 4D, sustainability assessments have always played a key role in our investment process. As such, we continue to favour those companies that have been forward-thinking and are capitalising on the decarbonisation opportunity while generating attractive returns for investors. In the US, this includes American Electric Power and NextEra Energy; both of which are investing heavily in energy transition and will unlikely be derailed by the recent SCOTUS decision. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: 4D Global Infrastructure Fund, 4D Emerging Markets Infrastructure FundThe content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. This commentary in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader. |

25 Aug 2022 - Equities responding to a higher rate environment

|

Equities responding to a higher rate environment Eley Griffiths Group August 2022 Global equity markets (ex-China) rebounded strongly in July. The Small Ordinaries Accumulation Index rallied +11.4% over the month, a significant outperformance against large caps which gained +5.5%. There was early indication that bad news is now being discounted into stock prices. Markets pushed higher despite the US CPI report for June the highest print in 41 years, 9.1% year on year compared to the 8.8% estimate. Equities took the number in its stride failing to extinguish the "risk on" sentiment. As predicted, The Federal Reserve (Fed) raised rates by 75bp in response and whilst Fed Chair Powell's broader messaging didn't overly change, comments that the US economy may be showing signs of slowing were less hawkish than expected. The war on inflation is being won. The market responded by pricing in a lower peak Federal Funds rate and increasing the likelihood that rates may be eased in 2023 reflecting the impact higher rates will have the on real economy. Locally, the Reserve Bank of Australia delivered +50bps after the Q2 CPI came in at 6.1% YoY, the highest since 1990. Once more, equity markets responded positively to the dovish post-meeting statements, "we don't need to return inflation to target immediately… we are seeking to do this in a way in which the economy continues to grow, and unemployment remains low" (Australian Strategic Business Forum, 20 July 2022 Governor Lowe). Outside non-gold resource names and agricultural stocks, the upswing was sectorally broad based. Standing out were those most beaten-up by inflation and central bank rate hike fears, namely Information Technology (+18%) and Financials (+15%). Focus now turns to the August corporate earnings results and whether investors have been heavy handed in their treatment of stocks. The lead from the US 2Q reporting season has been adequate. Attention will be trained on the impacts of inflation on operating cost structures, a higher rate environment and the health of the consumer. Funds operated by this manager: Eley Griffiths Emerging Companies Fund, Eley Griffiths Small Companies Fund |

24 Aug 2022 - The outlook for equities is unclear

|

The outlook for equities is unclear Airlie Funds Management July 2022 |

|

The outlook for equities is incredibly unclear. We have talked prior that markets are at the crossroads after a +10-year bull market - inflation and interest rates are on the rise and so central banks are reversing course after a decade plus of super easy policies. The early result of this, and exacerbated by the Ukraine invasion, is a return of market volatility. After being super strong in the March quarter, even commodity prices are now weakening, putting further pressure on the Aussie market. As fabled investor Peter Lynch says - "If you can only follow one piece of data - follow the earnings...". Given profit margins overall are at record highs; stimulus is unwinding; costs pressures abound; and consumers will likely have less disposable income - then an easy bear case for the direction of earnings can be outlined. PORTFOLIO POSITIONING

As bottom-up stock-pickers, we invest on company fundamentals: seeking conservative balance sheets, businesses that generate good returns and are managed by competent people. However, from a top-down perspective we want to avoid "unintended bets"; i.e., positioning the portfolio in a way that leaves it vulnerable to certain macro events playing out. The key macro event to watch this year is inflation. There is no doubt in the near term that inflation will continue to increase: most of the companies we speak to are seeing significant input cost (and increasingly labour) inflation, and have signalled their intent to pass this on in the form of higher prices. Since we think inflation is heading up in the near-term, it's important to make sure our portfolio owns businesses with pricing power, that can protect margins and pass on higher costs to end consumers. We have analysed our portfolio through this lens and think we are well positioned. Businesses like James Hardie, Woolworths, Wesfarmers, Macquarie, the banks, Aristocrat and CSL should all benefit from (or at least not suffer from) higher inflation. The market has been quick to reprice those businesses whose valuations had benefited from the "lower-for-longer" interest rate tailwind of the last decade, chiefly high PE structural growth stories, loss-making tech companies and REITs. We believe there are additional nuances to consider. We are avoiding businesses with high ongoing capex needs, as inflation makes it more expensive to stand still, and businesses with material exposure to floating-rate debt. Meanwhile, we spend our time sifting through the wreckage of heavily sold-off companies for opportunities where good businesses have been mispriced with respect to stock selection for the portfolio, we weigh four factors when considering an investment: Financial strength: We want to own businesses with conservative levels of gearing and strong cash flows. While corporate balance sheets are in great shape across the board, with average net debt to EBITDA for ASX200 companies of 1.8x (well below the 10-year median of 2.5x), our portfolio has an average net debt to EBITDA of 0.3x. Further, 38% of our portfolio companies are in fact net cash. We believe this sets us up for strong future returns, whether through dividends, special dividends, buybacks, investment or acquisitions. Management quality: We look for alignment with shareholders, whether that be through significant management shareholdings, or appropriate long-term incentives. The ultimate model of alignment for us is owner- managed businesses, where the original founder remains in control. We believe these businesses tend to outperform over the long term, and owner-managed businesses comprise c30% of our portfolio, compared to 10% of the ASX200. Valuation: We believe the returns a business generates drive the value of the business, and seek to invest where the above factors are underappreciated in the prevailing market share price. Funds operated by this manager: Important Information: Units in the fund(s) referred to herein are issued by Magellan Asset Management Limited (ABN 31 120 593 946, AFS Licence No. 304 301) trading as Airlie Funds Management ('Airlie') and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer documentation, offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for interests in any type of investment product or service. You should obtain and consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement ('PDS') and Target Market Determination ('TMD') and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making a decision to acquire, or continue to hold, the relevant financial product. A copy of the relevant PDS and TMD relating to an Airlie financial product or service may be obtained by calling +61 2 9235 4760 or by visiting www.airliefundsmanagement.com.au. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results and no person guarantees the future performance of any financial product or service, the amount or timing of any return from it, that asset allocations will be met, that it will be able to implement its investment strategy or that its investment objectives will be achieved. This material may contain 'forward-looking statements'. Actual events or results or the actual performance of an Airlie financial product or service may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. This material may include data, research and other information from third party sources. Airlie makes no guarantee that such information is accurate, complete or timely and does not provide any warranties regarding results obtained from its use. This information is subject to change at any time and no person has any responsibility to update any of the information provided in this material. Statements contained in this material that are not historical facts are based on current expectations, estimates, projections, opinions and beliefs of Airlie. Such statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and undue reliance should not be placed thereon. Any third party trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners and Airlie claims no ownership in, nor any affiliation with, such trademarks. Any third party trademarks that appear in this material are used for information purposes and only to identify the company names or brands of their respective owners. No affiliation, sponsorship or endorsement should be inferred from the use of these trademarks.. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced, or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Airlie. |