NEWS

14 Feb 2022 - The upcoming earnings season - like drinking from a fire hose

|

The upcoming earnings season - like drinking from a fire hose Spatium Capital January 2022 Twice a year, the earnings of various ASX-listed companies are reported. First, in February, providing a snapshot as at the end of December, and then again in August, following the Australian end of financial year on June 30th. Many see this as an opportunity to receive a health check on the current results and future trajectory of these listed companies. Despite the best attempts of forecasters, the unpredictable nature of how the market will respond to a company's earnings leaves many working feverishly to calibrate their respective positions, especially when anomalies are rife. For example, it is not uncommon for a company's stock price to increase when the market expects a greater decline in revenue than what is reported. Conversely, if a company does not achieve expected revenue targets (even if these revenues are positive), then it can result in a decline in the company's ticker price as forecasters adjust their valuations.

The 'bottom-line' may not always paint a clean picture, given 'up-and-coming' businesses often reinvest heavily in market share acquisition strategies (such as marketing, or developing new products). This subsequently drives up 'middle-line' costs with the hope of gaining future 'top-line' benefits. Without itemizing each variable that sits within the top to bottom line segments, we trust the point has been made - earnings season is complex. More so now, it seems, with new environmental, social and governance (ESG) metric expectations. Many businesses are now facing significant shareholder pressure to factor in ESG metrics. Whilst driving up middle line costs now, ESG so far appears to have significant customer and employee retention benefits, as well as being the public 'right thing to do'. The cynic may challenge whether these programs are truly driven by ESG good or future 'top-line' benefit. Whereas the optimist might assert that whilst either motive could be true, greater ESG benefit cannot be a bad thing, irrespective of the method(s) used to get there. This discussion calls into question the purpose of a company (generally speaking, to operate in self-interest) vs. the operation of a government (establishing the rules that do not allow this self-interest to operate unfettered). It is the classic economics example of 'who pays for the light bulbs in streetlamps?' The cynic argues that through the creation of jobs and payment of various taxes, it is the company who pays for streetlamp bulbs. The optimist, true to character, would just be happy they don't have to walk home in the dark. If earnings season wasn't already complex enough, the wider adoption of these new metrics can feel like trying to drink water from a fire hose. Like anything that is new, there will inevitably be kinks that need to be ironed out and parameters that need redefining. Perhaps the nirvana for these new metrics and their wide-scale adoption comes through regular policy and regulation revisions that encourage and guide companies to do what is considered socially better. Or maybe the onus is on the companies to willingly take on these new expectations from the community and thereby lobby the policymakers to formalise these shifts. Is only doing the right thing because you were told to do it enough in our customer-aware world? Either way, we suspect this debate is far from over and we watch with great intrigue how this may continue to impact future earnings seasons. We'd argue that this is only going to become increasingly complex in an environment where pundits and analysts are doing their best to quantify and price-in a rise in interest rates, ongoing supply chain constraints and inflationary pressures that are seemingly going unchecked. Relying on strictly linear forms of measurement or analysis is likely to negate an investing edge and conversely, too much information is likely to saturate one's bandwidth with little clarity on how to use it. We'd argue that the best way to navigate earnings season, or any other disruptive market cycle, is to not only remain convicted to one's tried and tested investment thesis, but also keep half an ear to the ground for emerging trends to consider how these might need to be examined |

|

Funds operated by this manager: |

11 Feb 2022 - Hedge Clippings |11 February 2022

|

|

|

|

Hedge Clippings | Friday, 11 February 2022 Magellan's, and Hamish Douglass's personal issues have been more than well documented in the media over the past couple of months, so there doesn't seem to be much gained by repeating them. The facts are all well known, thanks mainly to the size and success of the business since being established in 2006, and the high profile given to the individual along the way. However, there are some salient lessons to be learned - not only within Magellan, but also by other fund managers, investors, advisors and the industry as a whole, particularly the research houses, ratings agencies and consultants who have been part of the manager's success over the past 15 or so years. Magellan grew to be (and still is) a significant success story both in Australia and globally. It's easy to criticise, particularly for rival fund managers who might have struggled to attract FUM when so much was flowing into their rival, in spite of Magellan's relative underperformance over the last 5 years. To build FUM of $10bn is no mean feat, getting to around $100bn is extraordinary, and reflects not only performance, but outstanding business management and marketing/distribution along the way. Lesson #1: Key person performance is matched by key person risk. However, FUM of that magnitude requires dedicated management, as does listing and running a public company. Whilst Hamish Douglass's ability is undoubted in both areas, there's only so much one person can do, and how far his focus can stretch. Granted, Magellan had (and still has) a depth of management and a talented team beneath the chairman, but the focus was all Douglass externally leading to many thinking he may be wearing too many hats. Lesson #2: Size matters, but small and nimble has its benefits. Next, size. We have frequently shown that as FUM grows the ability to outperform one's smaller peers can become more difficult. Add in a series of concentrated portfolios - for instance the High Conviction Fund has exposure to just 8-12 stocks, while the larger Global fund has 20-40 stocks, which is still concentrated. A combination of size and concentration limits opportunity, and creates issues when or if the position, or the market turns against you. Size, or FUM, creates other imbalances. The benefit of size is that it opens the door to institutional mandates, not available to smaller managers due to the investors own concentration limits. As seen with Magellan, this can create business risk in the event that a major institution redeems. Lesson #3: Performance is more important than personality. We have often quoted Harold Geneen's "words are words and promises are promises, but only performance is reality". The Magellan Global Fund has returned just short of 14% per annum over the last 5 years which is a solid result, but the fund has underperformed relative to the market and many peers. However, the aura of Hamish, and his ability to hold an audience, is legendary, and the reputation of Magellan itself carried great weight with both investors, advisers, consultants and research houses. There used to be a saying in the early days of IT that "no one ever got fired for buying IBM". In the same way, an allocation to Magellan has been a safe option. The due diligence had been done by the rest of the market, so easier to go with the flow. That allowed the recent relative underperformance to be ignored, or at least not given the level of scrutiny by the gatekeepers and so called experts whose job it was to know and act accordingly. However, for a mere analyst within a ratings house, calling out that underperformance, or for that matter the key person risk involved in a star fund manager and consummate media performer, could be a brave, and possibly career defining act. Unless of course the proverbial has hit the fan and everyone's saying the same thing, and it's daily news in the financial press... Adjusting your research rating AFTER the event is akin to closing the gate after the horse has bolted, but don't get us started on the potential conflicts of interest involved in the fund manager paying for the ratings they receive. Lesson #4: Do your own research, and above all else, diversify. Not everyone has the knowledge or skill to fully analyse a fund's performance numbers, risk factors and KPI's, but there's enough core information available to all users of www.fundmonitors.com (no apologies for the plug) to be able to compare, measure, rank and make good decisions as a result. Forget the names and reputations for moment, do the numbers, and then diversify across strategy, asset class, manager and fund - allowing for the fact that Magellan might well remain part of that diversification. News & Insights Global Strategy Update | Magellan Asset Management With so much going on, where should your focus be? | Insync Fund Managers |

|

|

January 2022 Performance News Bennelong Concentrated Australian Equities Fund L1 Capital Long Short Fund (Monthly Class) |

|

|

If you'd like to receive Hedge Clippings direct to your inbox each Friday

|

11 Feb 2022 - Performance Report: L1 Capital Long Short Fund (Monthly Class)

| Report Date | |

| Manager | |

| Fund Name | |

| Strategy | |

| Latest Return Date | |

| Latest Return | |

| Latest 6 Months | |

| Latest 12 Months | |

| Latest 24 Months (pa) | |

| Annualised Since Inception | |

| Inception Date | |

| FUM (millions) | |

| Fund Overview | L1 Capital uses a combination of discretionary and quantitative methods to identify securities with the potential to provide attractive risk-adjusted returns. The discretionary element of the investment process entails regular meetings with company management and other stakeholders as well as frequent reading and analysis of annual reports and other relevant publications and communications. The quantitative element of the investment process makes use of bottom-up research to maintain financial models such as the Discounted Cashflow model (DCF) which is used as a means of assessing the intrinsic value of a given security. Stocks with the best combination of qualitative factors and valuation upside are used as the basis for portfolio construction. The process is iterative and as business trends, industry structure, management quality or valuation changes, stock weights are adjusted accordingly. |

| Manager Comments | The L1 Capital Long Short Fund (Monthly Class) has a track record of 7 years and 5 months and has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index since inception in September 2014, providing investors with an annualised return of 22.78% compared with the index's return of 7.15% over the same period. On a calendar year basis, the fund has only experienced a negative annual return once in the 7 years and 5 months since the start of its track record. Over the past 12 months, the fund's largest drawdown was -7.21% vs the index's -6.35%, and since inception in September 2014 the fund's largest drawdown was -39.11% vs the index's maximum drawdown over the same period of -26.75%. The fund's maximum drawdown began in February 2018 and lasted 2 years and 9 months, reaching its lowest point during March 2020. The fund had completely recovered its losses by November 2020. The Manager has delivered these returns with 6.66% more volatility than the index, contributing to a Sharpe ratio which has fallen below 1 three times over the past five years and which currently sits at 1.04 since inception. The fund has provided positive monthly returns 79% of the time in rising markets and 64% of the time during periods of market decline, contributing to an up-capture ratio since inception of 94% and a down-capture ratio of 3%. |

| More Information |

11 Feb 2022 - Performance Report: DS Capital Growth Fund

| Report Date | |

| Manager | |

| Fund Name | |

| Strategy | |

| Latest Return Date | |

| Latest Return | |

| Latest 6 Months | |

| Latest 12 Months | |

| Latest 24 Months (pa) | |

| Annualised Since Inception | |

| Inception Date | |

| FUM (millions) | |

| Fund Overview | The investment team looks for industrial businesses that are simple to understand, generally avoiding large caps, pure mining, biotech and start-ups. They also look for: - Access to management; - Businesses with a competitive edge; - Profitable companies with good margins, organic growth prospects, strong market position and a track record of healthy dividend growth; - Sectors with structural advantage and barriers to entry; - 15% p.a. pre-tax compound return on each holding; and - A history of stable and predictable cash flows that DS Capital can understand and value. |

| Manager Comments | The DS Capital Growth Fund has a track record of 9 years and 1 month and has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index since inception in January 2013, providing investors with an annualised return of 15.16% compared with the index's return of 8.91% over the same period. On a calendar year basis, the fund has experienced a negative annual return on 2 occasions in the 9 years and 1 month since the start of its track record. Over the past 12 months, the fund's largest drawdown was -7.43% vs the index's -6.35%, and since inception in January 2013 the fund's largest drawdown was -22.53% vs the index's maximum drawdown over the same period of -26.75%. The fund's maximum drawdown began in February 2020 and lasted 6 months, reaching its lowest point during March 2020. The Manager has delivered these returns with 2.12% less volatility than the index, contributing to a Sharpe ratio which has fallen below 1 four times over the past five years and which currently sits at 1.18 since inception. The fund has provided positive monthly returns 90% of the time in rising markets and 36% of the time during periods of market decline, contributing to an up-capture ratio since inception of 72% and a down-capture ratio of 51%. |

| More Information |

11 Feb 2022 - Performance Report: Bennelong Concentrated Australian Equities Fund

| Report Date | |

| Manager | |

| Fund Name | |

| Strategy | |

| Latest Return Date | |

| Latest Return | |

| Latest 6 Months | |

| Latest 12 Months | |

| Latest 24 Months (pa) | |

| Annualised Since Inception | |

| Inception Date | |

| FUM (millions) | |

| Fund Overview | |

| Manager Comments | The Bennelong Concentrated Australian Equities Fund has a track record of 13 years and has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index since inception in February 2009, providing investors with an annualised return of 16.29% compared with the index's return of 9.91% over the same period. On a calendar year basis, the fund has experienced a negative annual return on 2 occasions in the 13 years since the start of its track record. Over the past 12 months, the fund's largest drawdown was -12.4% vs the index's -6.35%, and since inception in February 2009 the fund's largest drawdown was -24.11% vs the index's maximum drawdown over the same period of -26.75%. The fund's maximum drawdown began in February 2020 and lasted 6 months, reaching its lowest point during March 2020. The Manager has delivered these returns with 1.66% more volatility than the index, contributing to a Sharpe ratio which has fallen below 1 five times over the past five years and which currently sits at 0.93 since inception. The fund has provided positive monthly returns 91% of the time in rising markets and 20% of the time during periods of market decline, contributing to an up-capture ratio since inception of 157% and a down-capture ratio of 93%. |

| More Information |

11 Feb 2022 - With so much going on, where should your focus be?

|

With so much going on, where should your focus be? Insync Fund Managers December 2021 Why it's all about Earnings Growth Companies that sustainably grow their earnings at high rates over the long term are called Compounders. Investing in a portfolio of Compounders is an ideal way to generate wealth for longer-term oriented investors that tend to also beat market averages with less risk. This chart shows the tight correlation between returns of the S&P 500 (orange line) and earnings growth (blue line) since 1926. NB: Grey bars are US recessions.

Insync's focus is on investing in the most profitable businesses with long runways of growth resulting in a portfolio full of Compounders. Inflation & interest rate impacts By focusing on identifying businesses benefitting from megatrends with sustainable earnings growth, means we do not need to concern ourselves with market timing, economic growth forecasts, inflation, or the future of interest rates. Throughout the last 100 years we've experienced periods of high economic growth, recessions, different inflation and interest rate settings, wars, pandemics, crisis and on it goes, but the one thing that has remained consistent... Over the long term, share prices follow the growth in their earnings. Media and many market 'experts' continue to be concerned about the risk of a sustained period of higher inflation. They worry over a short-term 'rotation' from quality growth stocks of the type Insync seek to own to value stocks. The latter in many cases is simply taken as equating to lowly rated companies and reopening stocks, such as airlines, energy, and transport. There are 3 problems with this view that can trap investors:

In sharp contrast good businesses remain strong at this stage of the cycle. They continue delivering the earnings growth that propel share prices over the long term. This is what makes their share price progress both sustainable and well founded. High margins and superior pricing power from Insync's portfolio of 29 highly profitable companies across 18 global Megatrends offers "the holy grail" of inflation busting companies. Pricing power, sound debt management and margin control allow great companies to handle inflation and interest rates well. LVMH and Microsoft) are portfolio examples that recently increased prices of their products with no impact on their sales growth. Profitability + Revenue Growth Short term, investors typically fret over interest rate rises and all growth stocks suffer initially, as they adopt an indiscriminate machine-gun approach to selling. Over time however, the more profitable businesses with strong revenue growth start to reassert their upward trajectory in their share prices, as investors appreciate their long-term consistent earnings power. Stocks with "quality growth" attributes, such as high returns on capital, strong balance sheets, and consistent earnings growth, have typically outperformed in past situations similar to what we face today (Mid-2014 through early 2016 and from 2017 through mid-2019. Source-Goldman Sachs).

This is in sharp contrast to stocks with strong revenue growth projections that also have negative margins or low current profitability. They are highly sensitive to changes in interest rates (These stocks propelled the short-term returns of many of the Growth funds in 2021). Many of them lack profit and cash flow, which doesn't give you much downside protection if they don't deliver. Many rely on the constant supply of new capital to fund their operations. These types of companies have very long durations because their present values are driven primarily by expectations of positive cash flows at a distant point in the future. We call this HOPE. As the saying goes; we don't rely on hope as a sound strategy. Stocks with valuations entirely dependent on future growth in the distant future are vulnerable to a dramatic drop in price if rates rise sharply or revenue growth expectations are reduced. This chart (performance of the Goldman Sachs NonProfitable Tech Basket) shows the downside risk to this sector of unprofitable high revenue growth companies. The index has fallen by close to 40% from its peak in February 2021. The index consists of non-profitable US listed companies in innovative industries. Source: Bloomberg Unsurprisingly, popular "new era" stocks held by high growth managers have also suffered a similar fate with examples noted below. Megatrends drive sustainable growth Megatrends enable us to locate the sustainable outsized market growth opportunity stock hunting-grounds (as well as help us avoid those that will dwindle). They are the 'fuel' to quality company's sustainable growth earnings. We are presently in the midst of one of the most disruptive innovation cycles in technological history. Thus, we resist the temptation of concerning ourselves with near term timing based 'market rotations' and changes in 'sentiment'. These distractions will otherwise prevent us from generating outsized returns in the years ahead. PWC consulting estimates that global GDP will be up to 14% higher in 2030 as a result of the accelerating development and take-up of AI. The equivalent of an additional $15.7 trillion USD. Source: PWC Internet of people V Internet of Things Our lives are already being impacted. In the past 5 years alone, almost all aspects of how we work and how we live - from retail to manufacturing to healthcare - have become increasingly digitised. The internet and mobile technologies drove the first wave of digital, known as the 'Internet of People'. Analysis carried out by PwC's AI specialists anticipate that the data generated from the Internet of Things (IoT) will outstrip the data generated by the Internet of People many times over. This is already resulting in standardisation, which naturally leads to task automation and the automatic personalisation of products and services - setting off the next wave of digital progress. AI exploits digitised data from people and things to automate and assist in what we do today, how we make decisions and how we find new ways of doing things that we've not imagined before.

From one of the all-time ice hockey greats, this very apt thought describes the way Insync frames its investment thinking. Despite the market's sentiment shift on the rotation trade, Insync's focus is on where the world is moving to. Data continues to show an acceleration in spending on pets, the rollout of 5G, health & wellness, and digital transformation. Major corporates expect elevated growth in technology to both accelerate and persist for the foreseeable future (according to a Morgan Stanley survey), in areas such as cloud computing, digital transformation and artificial intelligence. CIO intentions indicate that they expect to increase IT spend as a percentage of revenue over the next three years than they did pre-pandemic. The percentage of CIOs planning to increase spend versus those planning to decrease spend is known as the up-to-down ratio. It rose to 9.0, nearly 6x the pre-pandemic 2019 average. The best way to invest in a megatrend isn't always the obvious way! Semiconductors are driving the digital transformation of the world. Covid19 has had a profound impact on so many industries but one of the key areas everyone has started to care about, is silicon chips. This became abundantly clear when new car purchases were dramatically delayed because of chip supply chain shortages. Semiconductor chip usefulness has gone further than any other technology in connecting the world. The companies that produce them enable us to do pretty much everything, from the smartphones in our pockets to the vast data centres powering the internet, from electric scooters and cars to hypersonic aircraft, and pacemakers to weather-predicting supercomputers. Their manufacturing requires a high level of specialist technological know-how as it is a highly expensive, complex and a long process. It typically takes 3 months and 700 different steps to cover a silicon wafer with intricate etchings forming billions of transistors (microscopic switches that control electric currents and allow the chip to perform tasks). Semiconductor chips lay at the heart of the exponential transition that we're going to experience in computing over the next 5-15 years. More than we have ever witnessed before, and it will continue to grow exponentially. For example, AI applications process vast volumes of data-about 80 Exabytes pa today. This is projected to increase to 845 Exabytes by 2025. One Exabyte = One quintillion bytes = one thousand quadrillion bytes. Truly eye-watering numbers.

Funds operated by this manager: Insync Global Capital Aware Fund, Insync Global Quality Equity Fund |

10 Feb 2022 - Performance Report: Collins St Value Fund

| Report Date | |

| Manager | |

| Fund Name | |

| Strategy | |

| Latest Return Date | |

| Latest Return | |

| Latest 6 Months | |

| Latest 12 Months | |

| Latest 24 Months (pa) | |

| Annualised Since Inception | |

| Inception Date | |

| FUM (millions) | |

| Fund Overview | The managers of the fund intend to maintain a concentrated portfolio of investments in ASX listed companies that they have investigated and consider to be undervalued. They will assess the attractiveness of potential investments using a number of common industry based measures, a proprietary in-house model and by speaking with management, industry experts and competitors. Once the managers form a view that an investment offers sufficient upside potential relative to the downside risk, the fund will seek to make an investment. If no appropriate investment can be identified the managers are prepared to hold cash and wait for the right opportunities to present themselves. |

| Manager Comments | The Collins St Value Fund has a track record of 6 years and has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index since inception in February 2016, providing investors with an annualised return of 18.69% compared with the index's return of 9.93% over the same period. On a calendar year basis, the fund hasn't experienced any negative annual returns in the 6 years since the start of its track record. Over the past 12 months, the fund's largest drawdown was -5.4% vs the index's -6.35%, and since inception in February 2016 the fund's largest drawdown was -27.46% vs the index's maximum drawdown over the same period of -26.75%. The fund's maximum drawdown began in February 2020 and lasted 7 months, reaching its lowest point during March 2020. The fund had completely recovered its losses by September 2020. The Manager has delivered these returns with 3.84% more volatility than the index, contributing to a Sharpe ratio which has fallen below 1 two times over the past five years and which currently sits at 1.01 since inception. The fund has provided positive monthly returns 83% of the time in rising markets and 67% of the time during periods of market decline, contributing to an up-capture ratio since inception of 84% and a down-capture ratio of 28%. |

| More Information |

10 Feb 2022 - Performance Report: Bennelong Kardinia Absolute Return Fund

| Report Date | |

| Manager | |

| Fund Name | |

| Strategy | |

| Latest Return Date | |

| Latest Return | |

| Latest 6 Months | |

| Latest 12 Months | |

| Latest 24 Months (pa) | |

| Annualised Since Inception | |

| Inception Date | |

| FUM (millions) | |

| Fund Overview | There is a slight bias to large cap stocks on the long side of the portfolio, although in a rising market the portfolio will tend to hold smaller caps, including resource stocks, more frequently. On the short side, the portfolio is particularly concentrated, with stock selection limited by both liquidity and the difficulty of borrowing stock in smaller cap companies. Short positions are only taken when there is a high conviction view on the specific stock. The Fund uses derivatives in a limited way, mainly selling short dated covered call options to generate additional income. These typically have less than 30 days to expiry, and are usually 5% to 10% out of the money. ASX SPI futures and index put options can be used to hedge the portfolio's overall net position. The Fund's discretionary investment strategy commences with a macro view of the economy and direction to establish the portfolio's desired market exposure. Following this detailed sector and company research is gathered from knowledge of the individual stocks in the Fund's universe, with widespread use of broker research. Company visits, presentations and discussions with management at CEO and CFO level are used wherever possible to assess management quality across a range of criteria. |

| Manager Comments | The Bennelong Kardinia Absolute Return Fund has a track record of 15 years and 9 months and has outperformed the ASX 200 Total Return Index since inception in May 2006, providing investors with an annualised return of 8.2% compared with the index's return of 6.2% over the same period. On a calendar year basis, the fund has experienced a negative annual return on 3 occasions in the 15 years and 9 months since the start of its track record. Over the past 12 months, the fund's largest drawdown was -5.44% vs the index's -6.35%, and since inception in May 2006 the fund's largest drawdown was -11.71% vs the index's maximum drawdown over the same period of -47.19%. The fund's maximum drawdown began in June 2018 and lasted 2 years and 6 months, reaching its lowest point during December 2018. The fund had completely recovered its losses by December 2020. The Manager has delivered these returns with 6.45% less volatility than the index, contributing to a Sharpe ratio which has fallen below 1 times over the past five years and which currently sits at 0.69 since inception. The fund has provided positive monthly returns 87% of the time in rising markets and 33% of the time during periods of market decline, contributing to an up-capture ratio since inception of 17% and a down-capture ratio of 52%. |

| More Information |

10 Feb 2022 - Global Strategy Update

|

Global Strategy Update Magellan Asset Management January 2022 Hamish Douglass discusses why the less-threatening Omicron variant still comes with inflation implications, why he's recently invested in two companies exposed to structural growth in global travel and why today's stock market reminds him of 1999's. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Magellan Global Fund (Hedged), Magellan Global Fund (Open Class Units) ASX:MGOC, Magellan High Conviction Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund, Magellan Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged), MFG Core Infrastructure Fund |

10 Feb 2022 - Sailing into the wind

|

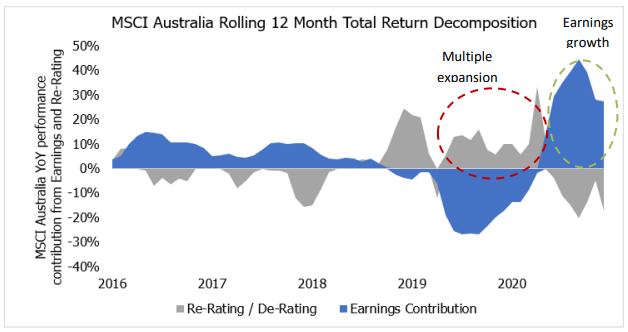

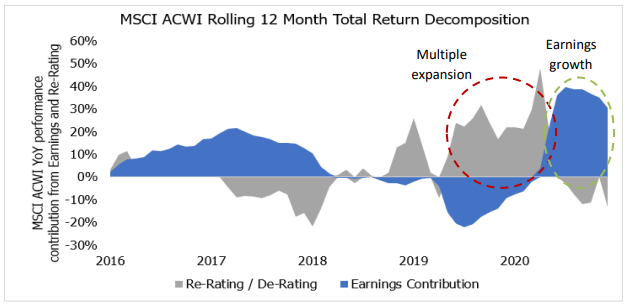

Sailing into the wind (Adviser & wholesale investors only) Alphinity Investment Management 24 January 2022 Sailing into the wind is a sailing expression that refers to a sail boat's ability to move, even if it is headed into the wind. To reach specific points, alternating the wind's direction between the starboard and the port is sometimes necessary. Equity markets similarly require the same agility to adjust for different market cycles and macro implications to deliver consistent returns for clients. The last (almost) two years of Covid-related repercussions have certainly tested even the best skippers' navigation skills and having the flexibility in your process to adjust when necessary has been invaluable. As we head into 2022 with concerns around economic growth and monetary stimulus likely peaking, the earnings cycle potentially maturing, and equity market valuations optically high, investment risks appear to be rising. At Alphinity we continue to let earnings leadership, on a stock by stock basis, guide us through the next phase in the cycle, wherever earnings upgrades may lead us (rather than being tied to a specific style or macro outcome). 2021 - A normal, abnormal yearNothing about the last 24 months since the Covid pandemic started has felt normal. Global equity markets (with Australia no exception) have however followed a surprisingly normal recession and recovery pattern, albeit faster and more aggressive than usual. Consistent with historical patterns, the first stage of the market recovery in 2020 was driven by valuation multiples expanding, with the market pricing in future earnings growth, which did not disappoint and drove the second stage of the recovery into 2021. The two charts below illustrate the similar return drivers of the MSCI Australia and MSCI World Indices, with the former enjoying stronger earnings growth, but also a larger multiple contraction at the index level over the last year. The key question from here is the expectation for each of these drivers (earnings and multiples) as we head into a new year. MSCI Australia following a normal post-recession market pattern - up c60% since the trough with the PE expanding from 14.5x to 20x, currently back down to 18x

Source: BoAML Data MSCI World has added c97% since the trough in March'20 with the PE expanding from 12x to 20x, currently back at 18x.

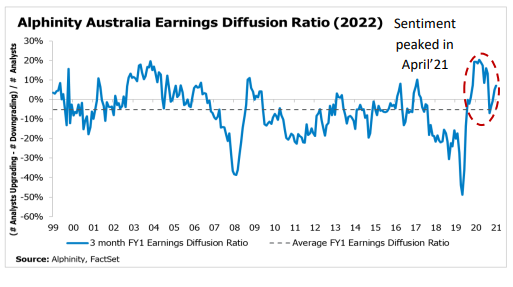

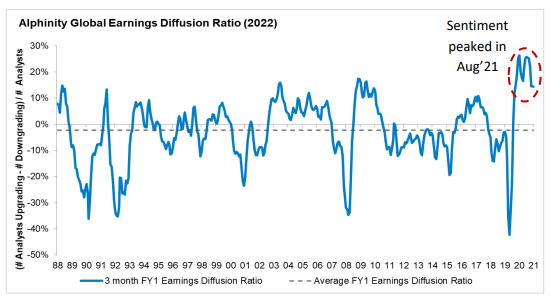

Source: BoAML Data Different points in the earnings cycle heading into 2022Global earnings revision breadth (or earnings sentiment as measured by the Alphinity Diffusion index, being the number of companies getting earnings upgrades vs downgrades) expanded to 30-year highs as analysts started pricing in the strong demand recovery and unprecedented corporate pricing power. Similarly in Australia, earnings sentiment soared to highs last seen in 2003, peaking in April 2021 driven by the early cycle commodity pullback, dropping into negative territory during lockdowns and finally stabilising in November 2021. Generally, these small upgrades still favour pro-cyclical earnings, but we are seeing some selective defensive positive earnings revisions coming through. Australian earnings cycle - Less clouding, but not yet clear

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg, 31 December 2021 Globally earnings upgrades are still dominating, but the trend is narrowing to fewer stocks. In terms of relative sector earnings revisions, the picture is getting more mixed compared to the clear cyclical and growth leadership we have seen over the last 12 months with some defensive sectors slowly creeping into positive territory. Global earnings cycle - Still positive but losing momentum

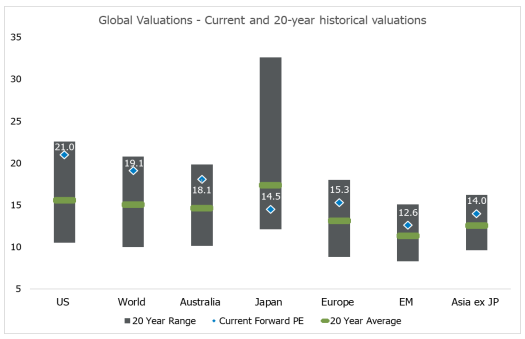

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg, 31 December 2021 High valuations offer less support and high dispersions increase vulnerabilitiesDespite the recent multiple contractions seen during 2021, most global equity markets are still trading above their long-term averages driven in part by low interest rates and excess liquidity. Strong performance in the last 18 months has seen pockets of the market becoming particularly stretched and therefore vulnerable to material changes in earnings and interest rate expectations, real or perceived. The valuation dispersion between the highest (80th percentile) and lowest (20th percentile) rated stocks is at a record high for the ASX200 and the MSCI World Index, with unprofitable tech a particular standout. Factor and style dispersion were also extremely high during 2020, which makes sense for a year marked by very high uncertainty or a recession and extreme volatility. This dispersion has reduced a bit during 2021 but remains at unusually high levels across several styles, such as value vs growth, given the strong recovery in the economy.

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg, 31 December 2021 Global equity markets still trading above their long-term average valuations

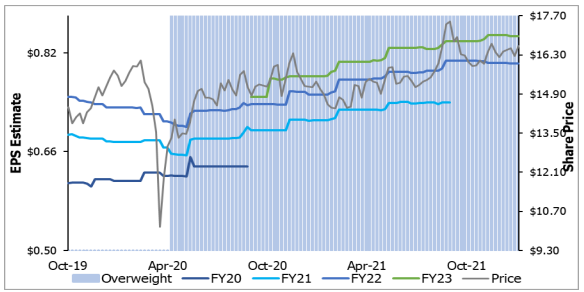

Source: Bloomberg, 31 December 2021 Adjusting the sails for the winds of changeAdd to this peaking, but still robust, global economic growth, stubborn inflation data, likely less central bank support and ongoing uncertainty around new Covid variants such as Omicron, is probably going to make navigating macro influences on markets more challenging this year. The increasing points of uncertainty suggest a more diversified, balanced approach will be required, focused on individual company stories rather than large thematic biases, with flexibility to react to material changes in the investment environment. Introducing some defensive characteristics also seems prudent, as long as you can identify the relative earnings story. Across our Australian funds we continue to follow the individual company earnings and where upgrades are coming from. Along those lines we have added to some more defensive positions such as Sonic, Amcor, Medibank and Treasury Wineries in the last few months. Global packaging company Amcor for example, offers a defensive earnings stream with strong cashflow generation and a solid balance sheet, which allow management the flexibility to do recurring buybacks and potential bolt-on acquisitions. Amcor has beaten earnings and upgraded its outlook at the last 6 quarterly reports, primarily driven by better than expected synergies with Bemis, but also better than feared passthrough of higher resin prices. Amcor's defensive qualities should see it deliver a steady return over the next 12 months and outperform the market on any potential correction. Amcor - offering a defensive earnings stream and strong cashflow generation

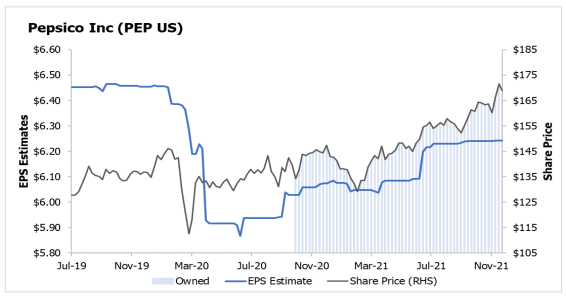

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg On the global side, we have continued to incrementally reduce our cyclical and higher PE growth exposure in favour of high-quality defensives such as Pepsico, Nextera and Nestle. Pepsi is a high quality, defensive consumer stock with strong pricing power and under-appreciated long-term revenue growth driven by strategic reinvestment under a new CEO, a mix shift to the higher growth snacks segment, targeted M&A and market share gains in beverages. Recent third quarter results displayed broad-based strength across the business, with management committed to offsetting rising inflationary pressures by leveraging strong brand investment and innovation to drive price increases and revenue management. Pepsi - driving earnings growth through strong pricing power and innovation

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg It seems likely that 2022 will be a more challenging year for markets, especially given the higher valuation starting point. It is through choppy waters like the present that we rely on our agile, style agnostic process to get us to our destination. As Thomas S. Monson once said, we cannot direct the wind, but we can adjust our sails. Author: Elfreda Jonker - Client Portfolio Manager |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Alphinity Australian Share Fund, Alphinity Concentrated Australian Share Fund, Alphinity Global Equity Fund, Alphinity Sustainable Share Fund |