NEWS

7 May 2021 - Managers Insights | Delft Partners on Taiwan

|

Australian Fund Monitors' CEO, Chris Gosselin, speaks with Robert Swift from Delft Partners about the Delft Partners Global High Conviction Strategy. Robert shares his thoughts regarding the tension around the South China Sea. Since inception in August 2011, the Strategy has risen +16.21% p.a. with an annualised volatility of 12%. Over that period, the Strategy has achieved Sharpe and Sortino ratios of 1.16 and 2.18 respectively, highlighting its capacity to achieve good risk-adjusted returns while avoiding the market's downside volatility. Funds operated by manager: Delft Partners Global High Conviction Strategy, Delft Partners Asia Small Companies Strategy, Delft Partners Global Infrastructure Strategy |

7 May 2021 - Inflation Preparation - Old is new again

|

Inflation preparation - Old is New Again Arminius Capital 23rd April 2021 Back when coins were originally made out of an alloy of silver and gold it was uncommon but not impossible to debase one's currency. The death penalty as a consequence of currency debasement seemed to inhibit the practice. The Lydian Empire in 700 BC (before they fell to the Persians) lays claim to inventing "coinage". Once the use of coins as a medium of exchange became commonplace, the Greeks were known to debase their currency from time to time. The Romans of course (in order to fund large wars or for natural disasters - beginning to sound familiar?) perfected the art. Currency debasement goes by many names and methods, amongst which "sweating" and "clipping" were popular. These days, the world's central banks and Treasury Departments are performing this role and the eventual result is becoming clearer: inflation.

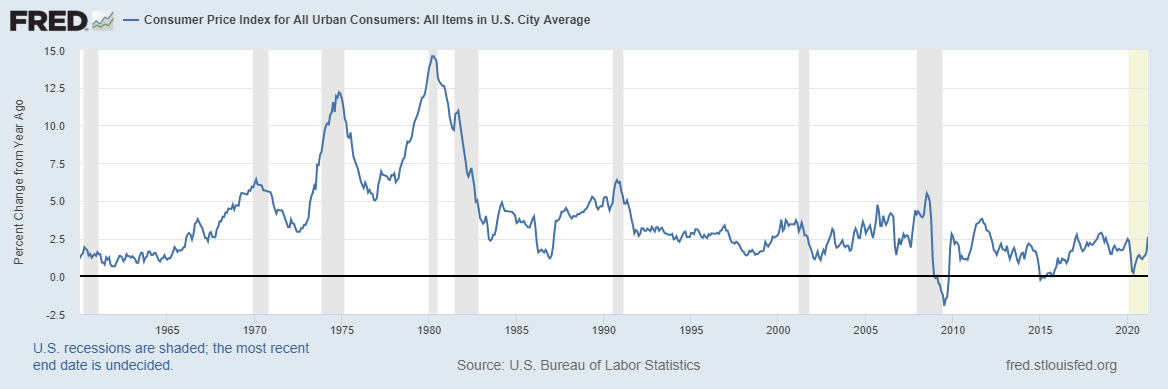

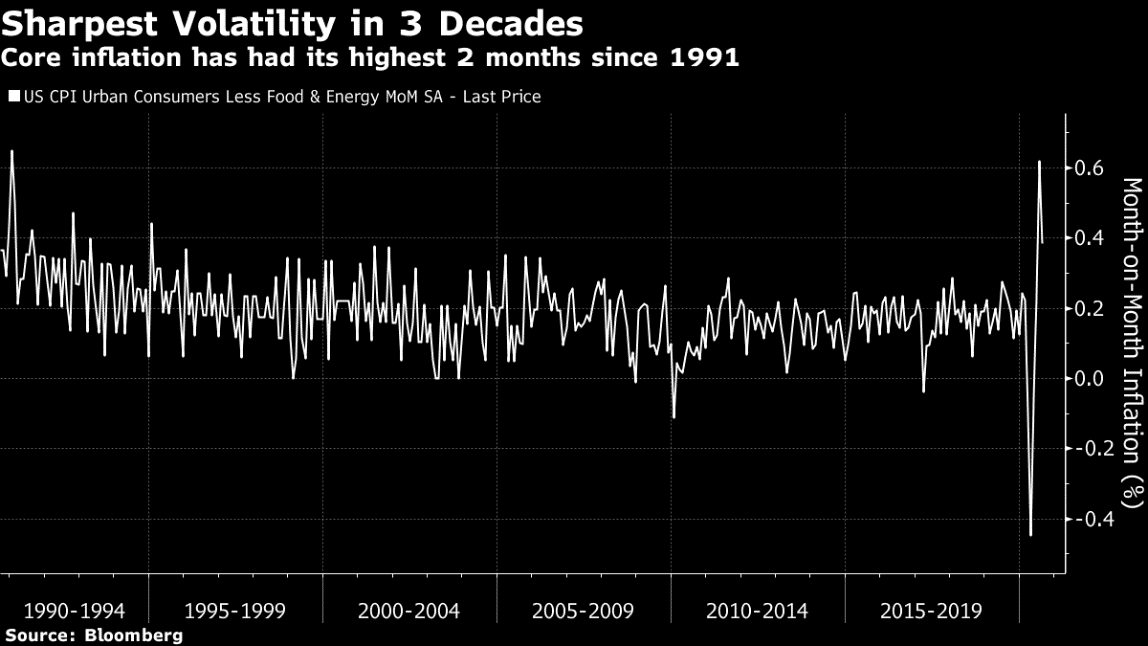

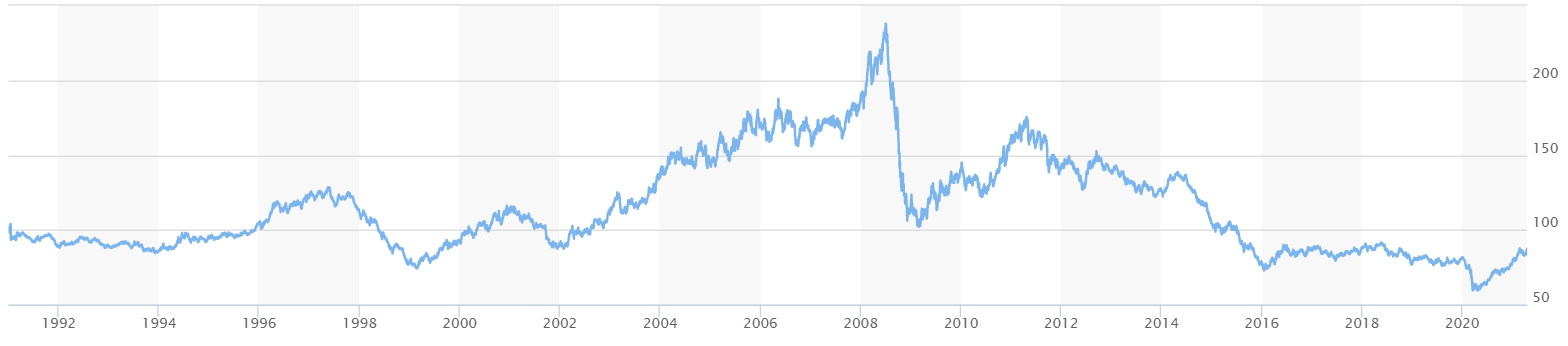

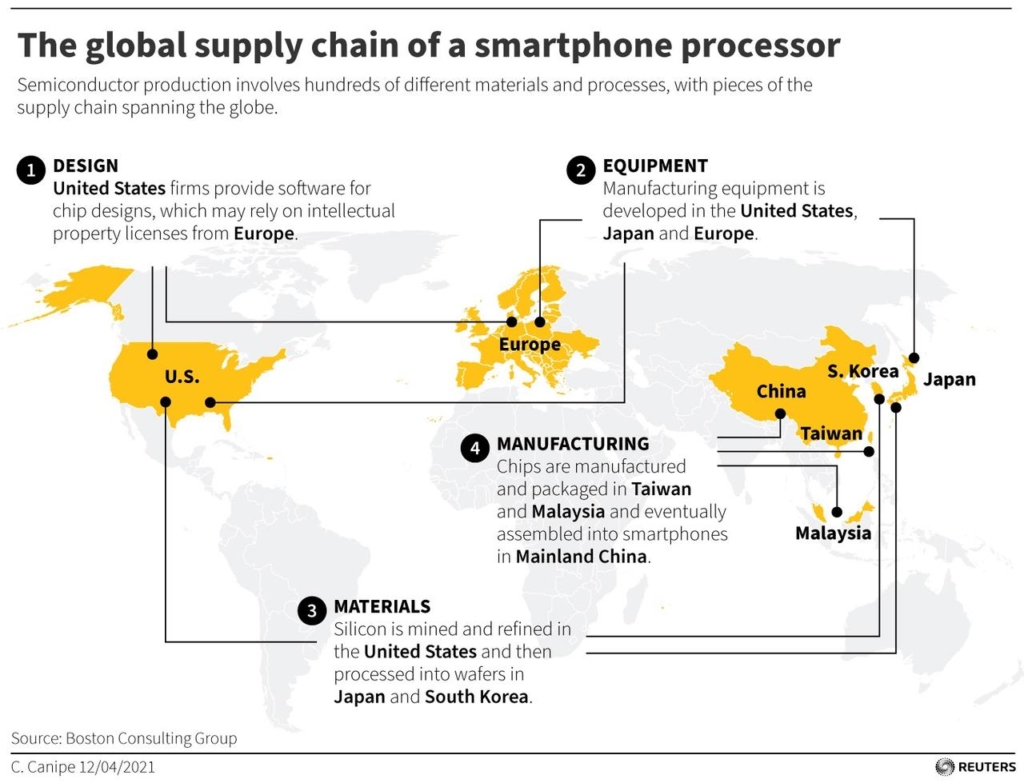

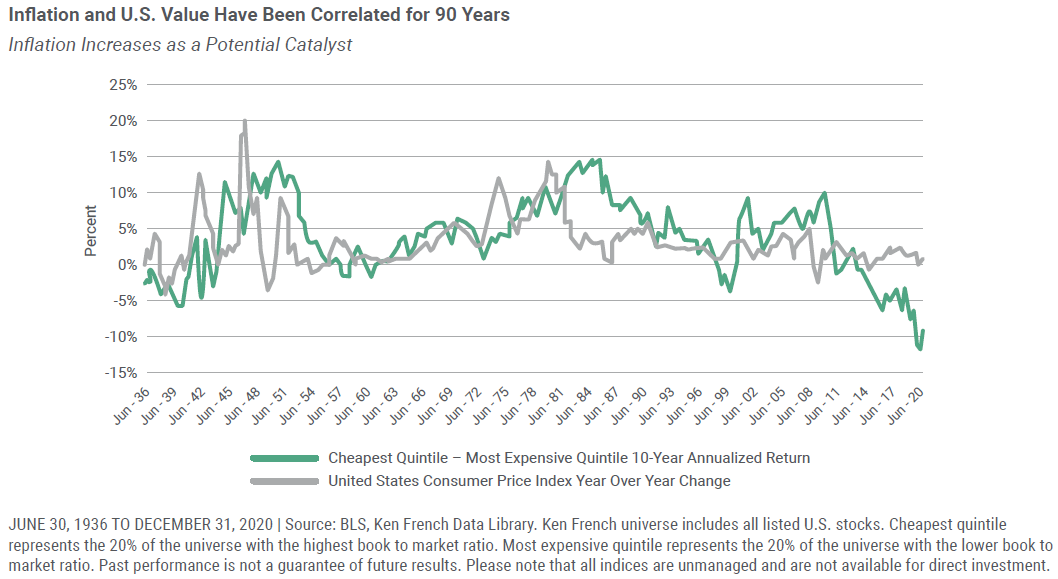

The chart above shows US consumer price index (CPI) inflation for the last sixty years. For those of us who can remember the 1960s and 1970s, history seems to be repeating itself. In the 1960s, the US government steadily increased its annual budget deficit in order to pay for the Vietnam War and new social programs. Consumer price index (CPI) inflation rose modestly at first, then it took off in the 1970s as a result of three key events - Richard Nixon ended the gold convertibility of the US dollar, OPEC quadrupled oil prices, and global commodity prices rocketed up. Inflation continued to accelerate despite the efforts of three US Presidents, until Paul Volcker (Chair of the Federal Reserve 1979-1987) raised official interest rates to a record 20% per annum in 1981. This time around, the Trump and Biden stimulus packages have injected an unprecedented amount of money into the US economy to combat the virus, at a time when the Federal budget deficit had already passed one Trillion dollars and US government debt was rapidly approaching 100% of GDP. These factors are inflationary in their own right, and they are reinforced by the imbalances which the COVID-19 pandemic has created in the US economy. The chart above shows US inflation on a month-to-month basis. For the last three decades it has been pretty stable, with no big monthly moves up or down, producing an annual average inflation rate of about 2%. Then in early 2020 the onset of the coronavirus pandemic triggered lockdowns, which set off a sharp deflation, followed by a sudden rebound in consumer demand and in CPI inflation. Is this inflationary surge just a temporary side-effect of COVID-19, or is it the beginning of a longer-term trend? We think that the US is about to see higher inflation - above 3% per annum by year end-2021. Inflation will rise in the US because the Federal Government's support packages have created an estimated USD$1.6 Trillion of "excess savings" in the bank accounts of US consumers - money which they were unable to spend on their usual activities like restaurants and travel. At the same time, the rapid recovery from the pandemic has caused supply bottlenecks in many sectors, from electronic goods to cars to housing. A shortage of cargo ships and containers has raised freight costs and delayed delivery dates. A shortage of builders and skilled labour has raised new house prices and slashed the number of houses for sale. The consumer goods giants Kimberley-Clark and Procter & Gamble have already announced across-the-board price rises, on the grounds of rising raw materials costs and higher transport expenses. Coca-Cola has recently announced price increases of the globally consumed beverage, citing identical reasons - higher commodity prices. Coke's CEO James Quincey this week stated, "We intend to manage those intelligently, thinking through the way we use package sizes and really optimize the price points for consumers". In true corporate-speak, by "optimize", he means "increase" the price points for consumers in order to offset Coke's increased production costs. Most importantly to observe, is that it is the prices of many commodities - from copper to iron ore to corn - that have risen sharply in recent months. The chart above shows the Bloomberg Commodities Index (BCOM) for the last thirty years. The last resources boom is clearly visible, peaking in March 2008, followed by a 75% fall over the next twelve years. The index has risen 47% from its bottom in April 2020, but it still has plenty more upside potential. It is now at the same level as it was in 2002 before the start of the last resources boom. Most commodity prices (except for iron ore) have been depressed for years because of over-supply, so they have considerable upside potential individually: the prices of strategic minerals and agricultural commodities could easily double from current levels. Commodity price rises feed very directly into inflation by raising manufacturers' raw material costs. There is an additional inflationary driver which will also raise manufacturers' costs. Semiconductors - the tiny silicon wafer chips which are essential for phones, computers, cars and all other electronics - are in short supply worldwide. The shortage began when the Trump Administration prevented Chinese companies from buying critical US patented technologies, including semiconductors. Not surprisingly, many Chinese companies started stockpiling semi-conductors as a precaution, and other companies followed suit. The semiconductor shortage worsened when the rapid US economic recovery in the last six months brought a surge in consumer demand, which encouraged retailers to rebuild their inventories and manufacturers to increase production. Very soon, the mostly Asian makers of semiconductors reached their capacity limits, so they increased prices, lengthened delivery times, and rationed new orders. Because new semiconductor capacity is expensive and takes at least two years to build, the semiconductor shortage will last until 2023. Last but not least, China. Chinese manufacturers face the same commodity price rises and semi-conductor shortage as the rest of the world, but there is also a political twist. Any retailer can tell you that imports from China have had a deflationary effect of consumer goods prices ever since China was allowed to join the World Trade Organization in 2001. As "the world's factory", China had lower input costs and lower labour costs, not to mention national and provincial governments which actively encouraged the creation and expansion of export industries. In recent years, however, the situation in China has changed. First, China's working-age population (those aged 16 to 59) has been falling since 2012, and average wages in China have been rising faster than GDP and inflation. Second, new entrants to the labour force are no longer the country boys and girls of the 1990s, who hadn't finished high school and were willing to work long hours in poor conditions. The new generation born in the 1990s is better educated, has higher expectations, and knows how to exploit its bargaining power. No more cheap China! Third, the 14th Five Year Plan for 2021-2025 de-emphasizes manufacturing exports in favour of domestic consumer demand, and it prioritizes investing in high tech industries. These objectives reflect what is happening on the ground: labour-intensive industries (e.g. textiles) have been moving from China to cheap-labour countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Bangladesh. Fourth, Xi Jinping has committed China to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Conclusion: China is no longer a deflationary force. In June 2020, when we started predicting higher inflation in the US, we thought that it would only spread very slowly to other countries, because the US dollar would fall against currencies such as the Australian dollar. We still expect the US dollar to fall, but recent trends in global inflation drivers -commodity prices, shipping delays, semiconductor shortages, and China - imply that inflation will be a global phenomenon. Source: Brandes Investment Partners What sort of stocks do well in times of inflation? The chart above shows how rises in inflation (grey line) have been correlated with higher share prices for value stocks (green line) since 1936. Value stocks are companies trading on lower price-earnings ratios (P/E) than the market average; they are often cyclicals, and usually in sectors such as banking, mining, energy, building materials, manufacturing and industrial supplies. As a class, value stocks underperformed the market from 2008 to 2020, but they have picked up dramatically since the vaccine good news of November 2020. What should Australian investors do to prepare for inflation?

Funds operated by this manager: |

6 May 2021 - Six reasons to not worry about inflation

5 May 2021 - Five Forces in International Equities Investors May Be Underestimating

5 May 2021 - Challenging Times for the Market's Speculative Elements

|

Challenging Times for the Market's Speculative Elements Andrew Clifford, Co-Chief Investment Officer, Platinum Asset Management 1st May 2021 We are now more than one year on from the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent initial lockdowns that resulted in a collapse in global economic activity and stock markets. While the pathway of the virus has been one of rolling waves in response to lockdowns, reopenings and now the rollout of vaccines, since the March 2020 lows, economic activity has experienced a strong and steady recovery, as have stock markets. Indeed, many of the world's major stock markets have comfortably surpassed their pre-COVID highs[1]. Fuelling this recovery in both economies and stock markets has been unprecedented (peace time) government deficit spending, funded through the printing of money. The question is, where to now? It is highly likely that the global economy will continue its strong recovery path over the course of the next two years. In concert with this recovery, government bond yields will likely head higher, which will prove challenging for the speculative elements within stock markets. Economic activity will likely continue to recover There are numerous reasons to expect that global economies will continue to recover. The most obvious is the ongoing reopening of economies, as vaccination programs take us toward the post-COVID era. With current headlines focused on the failure of vaccination rollouts and the outbreak of new variants of the virus, this may seem an overly optimistic statement to many. However, the success of the vaccination programs in the US and the UK, where 32% and 46% of each population respectively has received at least one vaccine dose, shows what can be achieved once health systems swing into gear[2]. Where vaccination programs have been slow to start in some locations, such as Europe, an acceleration is likely, especially as the availability of dosages continues to improve. Variants in the virus are an expected setback, but fortunately the vaccines are being refined to address the variants, as they normally would with the annual flu vaccine. Over the course of 2021, it is highly likely that we will move toward a situation where we return to freedom of movement across the world's major economies. With this, we expect industries such as travel and leisure will continue their recovery, and with that, elevated levels of unemployment will continue to fall. With a light at the end of the tunnel on COVID and rising employment, consumer confidence has started to bounce back (see Fig. 1). Fig. 1: US Consumer Confidence Bouncing Back As such, a release of pent-up consumer demand across a range of goods and services should be expected. Indeed, households are well-positioned to increase their spending, as large portions of government payments last year were saved and not spent, resulting in unprecedented increases in savings rates (See Fig. 2). Fig. 2: US Households Well-Positioned to Spend Additionally, in the US, consumers' bank accounts will be further inflated, with the recent passing of the US$1.9 trillion fiscal package. It is estimated that US consumers would need to spend an additional US$1.6 trillion dollars, or 7.5% of GDP, just to return to trend savings levels.[3] The recovery from the COVID-19 collapse is likely to be a very strong rebound that will play out over the next two to three years. Given the levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus across the globe during 2020 and 2021 to date, the US will be at the epicentre of the recovery. The ongoing stimulus efforts in the US, including a potential additional US$3 trillion of spending on infrastructure and healthcare over the next decade, make the rest of the world's efforts pale into insignificance. Indeed, China appears to be stepping back from stimulus programs, having already achieved a strong economic recovery. Nevertheless, the US stimulus will help growth in Asia and Europe via the trade accounts, as is already apparent in the strong recovery in China's trade surplus (see Fig. 3). Fig. 3: China's Trade Surplus Expands Long-term interest rates will likely move higher with the recovery As a result of the strong rebound in economic activity, interest rates will likely rise and indeed, they already have. The reference here is to long-term interest rates, such as the yield on the US 10-year government bond, rather than short-term interest rates set by central banks (e.g. the Reserve Bank of Australia). In the fastest-recovering economies, US 10-year government bond yields have increased from 0.51% in August 2020 to 1.74% at the end of March, while Chinese 10-year government bond yields have risen from their April 2020 lows of 2.50% to 3.21% at the end of March (see Fig. 4). Fig. 4: US and China 10-Year Bond Yields on the Rise In both cases, these yields have returned to pre-COVID levels. It is not surprising that yields on government bonds are rising, as this is generally the case during a recovery. The issue is just how much further they may rise, given expectations for a very robust growth environment in 2021, the substantial amount of new bonds that will be issued in the months ahead and nascent signs of inflationary pressures. Daily readings of consumer prices already show inflation heading back to levels last seen in mid-2019. As we discussed in our December 2020 quarterly report[4], markets in a broad range of commodities and manufactured goods are seeing shortages in supply, resulting in significant increases in prices. One high-profile example has been the auto industry having to cut production due to shortages in the supply of components. Given the complexity of supply chains and the various factors that have been impacting them in recent years, such as the trade war and then the sudden collapse and recovery in demand in 2020, predicting how long such shortages will persist is difficult. However, it is interesting that these price rises, usually associated with the end of an economic cycle, are occurring at the start of the cycle instead. Beyond the current supply shortages and associated price rises, the longer-term issue for inflation is how governments will finance their fiscal deficits. As we have discussed in past quarterly reports, when governments use the banking system (including their central banks) to finance deficits, it results in the creation of new money supply. The idea that the creation of money supply in excess of economic growth is inflationary, has lost credibility in recent years, as inflation didn't arrive with the quantitative easing (QE) policies of the last decade. However, the mechanisms by which banking systems are funding current fiscal and monetary policies of their governments are clearly different to what was applied during QE. Rather than delve into a deep explanation, we would simply point to the extraordinary growth in money supply aggregates, where in the US, M2[5] increased by a record annual rate of 25% almost overnight in mid-2020. These types of increases did not occur during the last decade of QE policies. Further growth in M2 awaits in the US, following the latest rounds of fiscal stimulus, though the percentage growth figures will at some point fall away as we pass the anniversary of last year's outsized increases. So, we have a strong economic recovery from the ongoing reopening post COVID, fuelled by fiscal stimulus, already tight markets in commodities and manufactured goods, plus excessive money growth. Given that we also have central banks committed to keeping short-term interest rates low for the foreseeable future and allowing inflation to exceed prior target levels, it is hard to see how we can avoid a strong cyclical rise in inflation. It is an environment where there is likely to be ongoing upward pressure on long-term interest rates. To see US 10-year Treasury yields above 3%, a level last seen in only 2018, would not be a surprising outcome. Rising long-term interest rates will represent a challenge for the bull market in growth stocks In recent years, we have emphasised the two-speed nature of stock markets globally. As interest rates fell and investors searching for returns entered the market, their strong preference was for 'low-risk' assets. At different times they have found these qualities in defensive companies, such as consumer staples, real estate and infrastructure, and at other times, in fast-growing businesses in areas such as e-commerce, payments and software. At the same time, investors have been at pains to avoid businesses with any degree of uncertainty, whether that be natural cyclicality within their business or exposed to areas impacted by the trade war. Last year, this division was further emphasised along the lines of 'COVID winners', such as companies that benefited from pantry stocking or the move to working from home, and 'COVID losers', such as travel and leisure businesses. Over the last three years, these trends within markets created unprecedented divergences in both price performance and valuations within markets. However, as we noted last quarter, this trend started to reverse at the end of 2020, as a combination of successful vaccine trials and the election of US President Biden pointed to a clearly improved economic outlook. The result was 'real world' businesses in areas such as semiconductors, autos and commodities started to see their stock prices perform strongly and this has continued into the opening months of 2021. Meanwhile, the fast-growing favourites continued to perform into the new year, though these have since faded as the rise in bond yields accelerated. Many high-growth stocks have seen their share prices fall considerably from their recent highs, with bellwether growth stocks such as Tesla (down 27% from its highs), Zoom (down 45%) and Afterpay (down 35%).[6] Theoretically, rising interest rates have a much greater impact on the valuation of high-growth companies than their more pedestrian counterparts. As such, it is not surprising to see these stocks most impacted by recent moves in bond yields and concerns about inflation.[7] Many will question whether this is a buying opportunity in these types of companies. While they may well bounce from these recent falls, we would urge caution on this front, as for many (but not all) of the favourites of 2020 we would not be surprised to see them fall another 50% to 90% before the bear market in these stocks is over. If our concerns regarding long-term interest rates come to fruition, this will be a dangerous place to be invested, and as we concluded last quarter, "when a collapse in growth stocks comes, it too should not come as a surprise". If there is a major bear market in the speculative end of the market, how will companies that investors have been at pains to avoid in recent years (i.e. the more cyclical businesses and those that have been impacted by COVID-19) perform? While these companies have seen good recoveries in their stock prices in recent months, generally they remain at valuations that by historical standards (outside of major economic collapses) are attractive. It should be remembered there are two elements to valuing companies: interest rates and earnings. Of these, the most important is earnings, and these formerly unloved companies have the most to gain from the strong economic recovery that lies ahead. As such, we would expect good returns to be earned from these businesses over the course of next two to three years. For many, the idea that one part of the market can rise strongly while the other falls, seems contradictory, even though that is exactly what has happened over the last three years. In this case, for reasons outlined in this report, we are simply looking for the relative price moves of the last three years to unwind. We only need to look to the end of the tech bubble in 2000 to 2001 for an indication of how this may play out - when the much-loved 'new world' tech stocks collapsed in a savage bear market, while the out-of-favour 'old world' stocks rallied strongly. This was a period where our investment approach really came to the fore, delivering strong returns for our investors. DISCLAIMER: This article has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006, AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management ("Platinum"). This information is general in nature and does not take into account your specific needs or circumstances. You should consider your own financial position, objectives and requirements and seek professional financial advice before making any financial decisions. You should also read the relevant product disclosure statement before making any decision to acquire units in any of our funds, copies are available at www.platinum.com.au. The commentary reflects Platinum's views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. [1] Source: FactSet Research Systems. [2] Source: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations#what-share-of-the-population-has-received-at-least-one-dose-of-the-covid-19-vaccine. As at 3 April 2021. [5] M2 includes M1 (currency and coins held by the non-bank public, checkable deposits, and travellers' cheques) plus savings deposits (including money market deposit accounts), small time deposits under $100,000, and shares in retail money market mutual funds. Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2SL [6] As at 31 March 2021. [7] Growth companies tend to rely on earnings in the more distant future. When valuing a company, future earnings are discounted back to a present value using a required rate of return, which is related to bond yields. As bond yields rise, the discounting process leads to a lower value in today's dollars, for the same level of future earnings. Funds operated by this manager: Platinum Asia Fund (C Class), Platinum Japan Fund (C Class), Platinum International Fund (C Class), Platinum Unhedged Fund (C Class), Platinum European Fund (C Class), Platinum International Brands Fund (C Class), Platinum International Health Care Fund (C Class), Platinum International Technology Fund (C Class), Platinum Global Fund, Platinum International Fund (P Class), Platinum Unhedged Fund (P Class), Platinum Asia Fund (P Class), Platinum European Fund (P Class), Platinum Japan Fund (P Class), Platinum International Brands Fund (P Class), Platinum International Health Care Fund (P Class), Platinum International Technology Fund (P Class) |

5 May 2021 - Inside the bond market sell-off

|

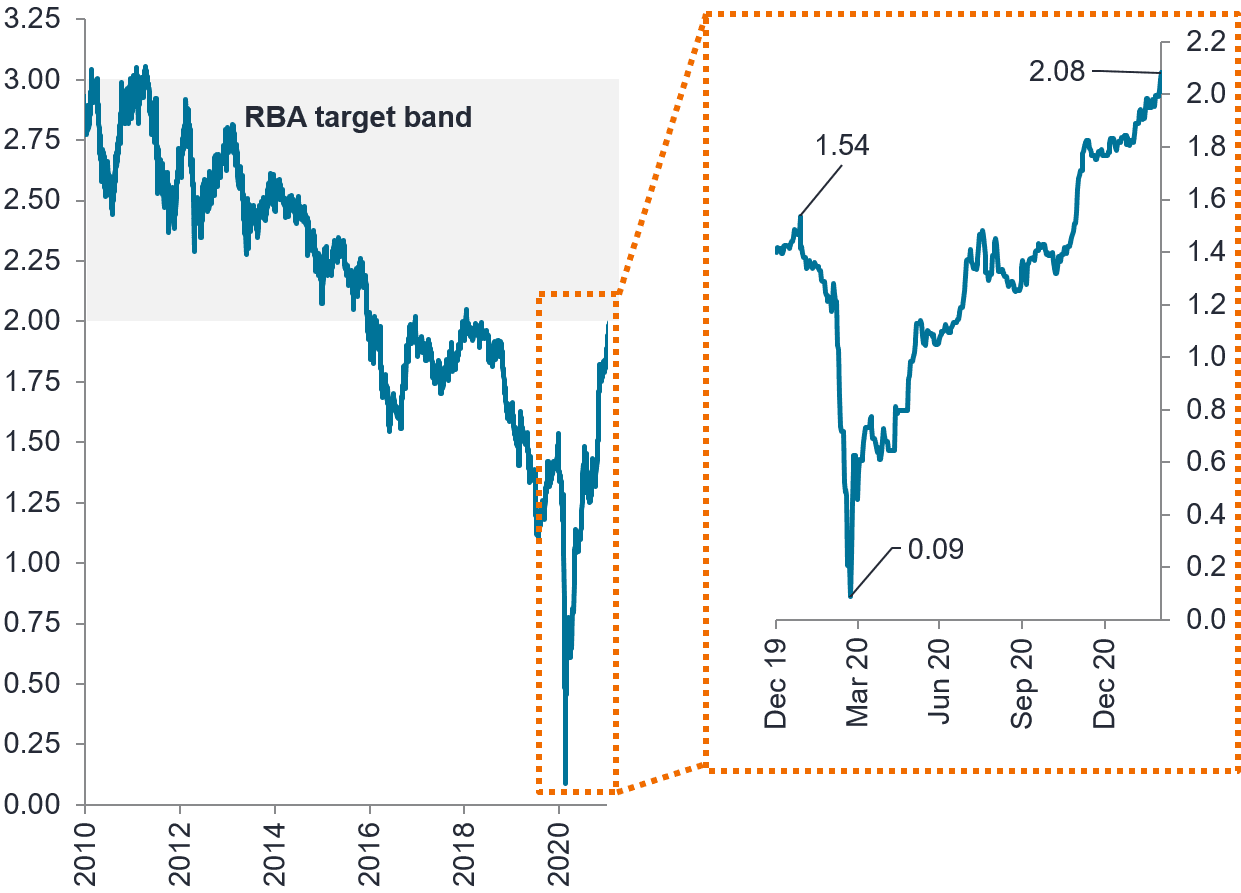

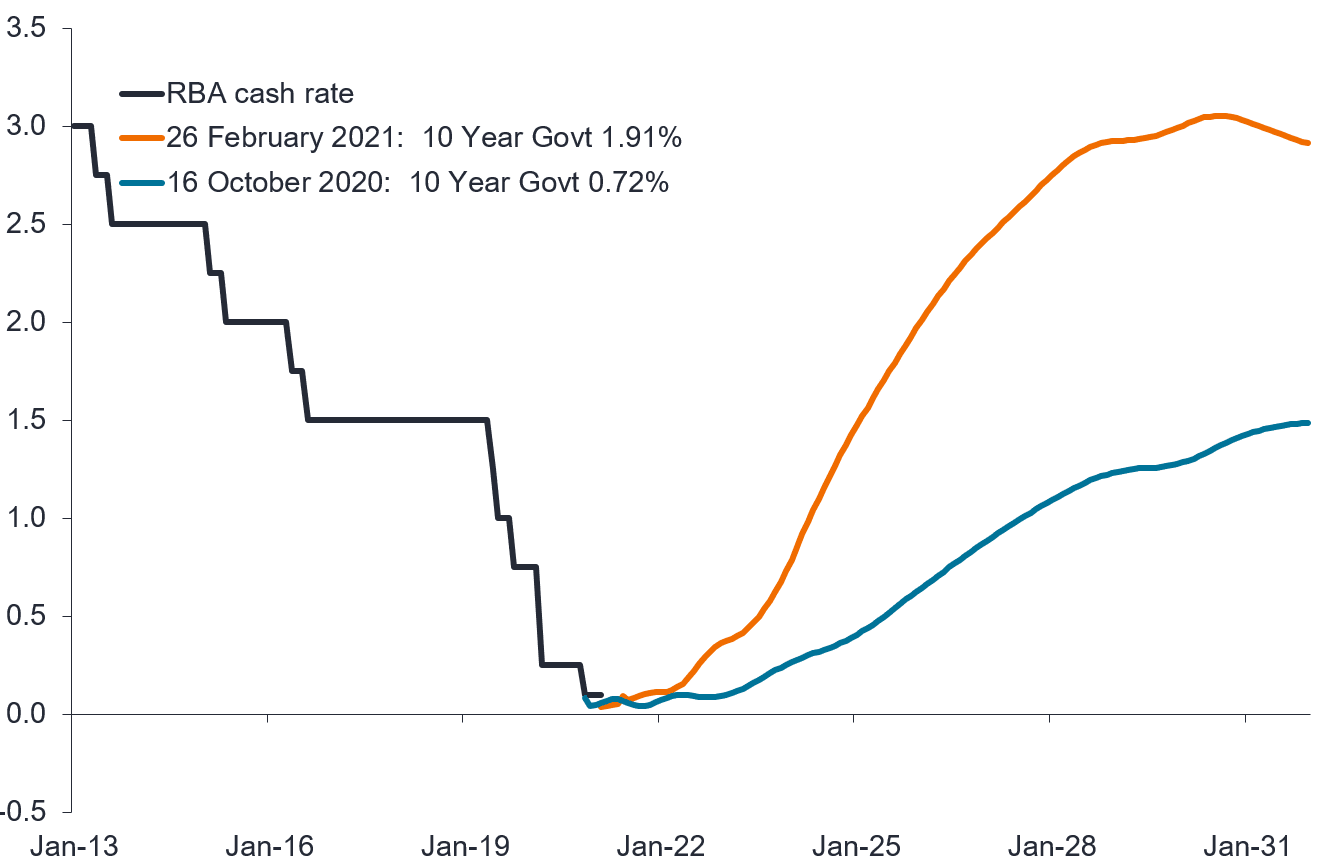

Inside the bond market sell-off Jay Sivapalan, CFA, Janus Henderson Investors March 2021 Over February the Australian bond market1 was down approximately 3.5%, suffering its biggest negative monthly return since 1983. In combination with its negative return in January, this episode essentially wipes 80% of the bond market's 2020 returns. Meanwhile, the 10 Year Australian Government bond yield has almost tripled since the lows experienced in 2020. While oonly the rates market has been affected so far, in our view this could extend into risk assets (such as equities, high yield and investment grade credit) if central banks don't intervene in a coordinated fashion to avoid a 'taper tantrum' style sell-off. The ingredients for a bond market sell-off have been brewing for some time, and while hard to predict the turning point, as active managers we must be poised to re-position our portfolios and identify investment opportunities. The three forces responsible 1. Rising Inflation expectations:

Chart 1: Australian 10-year breakeven inflation rate (%) Source: Bloomberg, ABS, Australian 10-year breakeven inflation rate to 4 March 2021. 2. Rising cash rate expectations:

Chart 2: Australian implied OIS forward 1m cash rate (%) Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, monthly to February 2021, spot 26 February 2021.

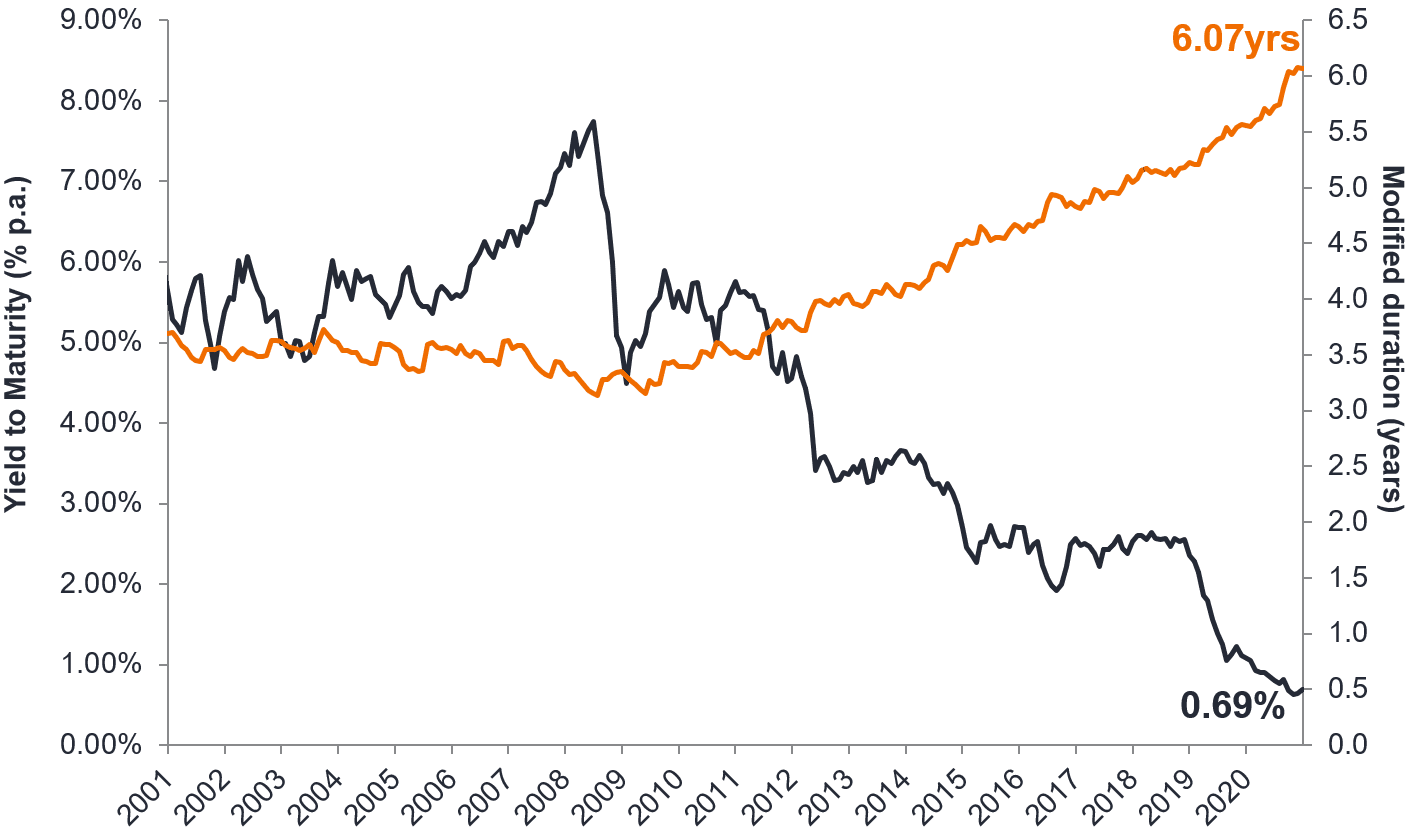

Chart 3: Yield to maturity and modified duration on the Bloomberg AusBond 0+ Yr Index Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as at 31 December 2020. Index: Bloomberg Ausbond Composite 0+ Yr Index. Note: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. 3. Question marks over central bank commitment:

How we are navigating the turmoil Effectively navigating the more volatile rising rate environment at the key turning points will be vital given the magnitude of interest rate risk (duration). Ultimately, as yields rise, we believe it is worth taking some duration risk to capture higher yields, especially if markets overshoot. Higher bond yields when cash rates are anchored at close to zero present very steep yield curves and the opportunity for investors to participate in both the yield and roll-down effect that adds to performance. Today a 10-year risk free government bond, if nothing happens in markets over the next year, can deliver a return that's at least twice that of a five-year major bank floating rate corporate bond2. These are exactly the type of opportunities active managers wait for even if some volatility in the near-term needs to be tolerated. One will only know after the fact whether the strategy went too early or too late. The team have also been focusing on capital preservation strategies to protect against a breakout in inflation expectations. Below is an overview of our investment strategy: Rates: Duration:

Inflation protection:

Spread sectors3: Having participated in the meaningful rally of spread sectors, we feel prudent to take some profit while valuations are at peak levels in the post-COVID market rally. Semi-government debt:

Credit protection:

Investment grade credit:

High yield:

We are intentionally still exposed to credit markets, but the above provides some room for risk taking should markets become unstable. This year is shaping up to be one where active interest rate strategies, including taking advantage of higher yields, may overshadow excess returns from spread sectors. Accordingly, our strategies will emphasise this from time to time as prevailing market conditions offer investment opportunities. While we expect some volatility and drawdown, near-term volatility presents an opportunity for active managers. Ultimately, higher bond yields restore the defensive characteristics and create better value for the asset class. 1. Australian Bond Market as measured by the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index. 2. Based on no change to the current bond yield of 1.91% for 10-year Australian Government bonds and the estimated yield of an Australian five-year major bank floating rate notes of 0.45% (as at 26 February 2020). 3. The above are the Portfolio Managers' views and should not be construed as advice. Sector holdings are subject to change without notice. This information is issued by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited (AFSL 444266, ABN 16 165 119 531). The information herein shall not in any way constitute advice or an invitation to invest. It is solely for information purposes and subject to change without notice. This information does not purport to be a comprehensive statement or description of any markets or securities referred to within. Any references to individual securities do not constitute a securities recommendation. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. Whilst Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited believe that the information is correct at the date of this document, no warranty or representation is given to this effect and no responsibility can be accepted by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited to any end users for any action taken on the basis of this information. All opinions and estimates in this information are subject to change without notice and are the views of the author at the time of publication. Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited is not under any obligation to update this information to the extent that it is or becomes out of date or incorrect. Funds operated by this manager: Janus Henderson Australian Fixed Interest Fund, Janus Henderson Conservative Fixed Interest Fund, Janus Henderson Diversified Credit Fund, Janus Henderson Global Equity Income Fund, Janus Henderson Global Natural Resources Fund, Janus Henderson Tactical Income Fund, Janus Henderson Australian Fixed Interest Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Conservative Fixed Interest Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Cash Fund - Institutional, Janus Henderson Global Multi-Strategy Fund |

3 May 2021 - Beware the beauty contest

|

Beware the beauty contest Charlie Aitken, Aitken Investment Management 20th April 2021 When reflecting on the past year, one notable takeaway for the AIM investment team is to be mindful of keeping our focus on business fundamentals rather than attempting to profit from whatever narrative is driving the market. This sounds simple enough on paper, but resisting the temptation of falling into this 'narrative fallacy' is quite difficult to achieve in practice - to such an extent that many investors step into this mindset without even realising it. The reason is deceptively simple: by definition, the vast bulk of daily news we all consume has almost nothing to do with the fundamental drivers of long-term value. Instead, daily news flow shapes the short-term expectations that drive the dominant 'narrative' in markets. To understand why we believe it is critical for investors to differentiate between fundamentals and narrative, we turn to John Maynard Keynes. Though primarily remembered as an economist, Keynes managed the King's College endowment at Cambridge from 1921 to 1946 with great success, delivering a tenfold return over a period where UK markets were essentially flat. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes addresses the impact of market expectations on prices: The actual, private object of the most skilled investment today is 'to beat the gun'; [...] to outwit the crowd, and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow. This may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees. There have been some fascinating real-world tests that explore this mindset. The Financial Times posed the following question to its readers in 2015: Guess a number from 0 to 100, with the goal of making your guess as close as possible to two-thirds of the average guess of all those participating in the contest. Suppose there are three participants who guessed 40, 60 and 80. In this case, the average guess would be 60, two-thirds of which is 40, meaning the person who guessed 40 would win. In theory, a large group of people guessing a random number between 0 and 100 will eventually average out to 50. However, a 'first-degree' thinker would likely reach that conclusion, and then guess 33 (equal to two-thirds of 50). A 'second-degree' thinker might conclude that there will be enough first-degree thinkers to move the average guess closer to 33, so the 'smart' guess would be 22 (two-thirds of 33). The 'third-degree' thinker would guess 15 (two-thirds of 22), the 'fourth-degree' would guess 10 (two-thirds of 15), and so on. (In reality, the average guess in the Financial Times puzzle was 17.3, meaning the 'correct' guess was 12). Carried to its logical conclusion, it becomes obvious that the problem inherent in such a game is that there is a circular reference: each participant's guess alters the outcome, meaning contestants end up trying to guess what the other players might be guessing, and adjust their own guess accordingly. There is no point at which one can confidently get off this train of thought in the knowledge your answer is correct. The concept has come to be known as the Keynesian Beauty Contest. Real-world examples This concept quite accurately describes a market where the participants stop paying attention to the fundamentals of an asset, but rather attempt to speculate about what other people might pay for the asset at some point in future. Under such conditions, the best 'narrative' attracts the most investor interest. Sure as night follows day, inflows follow interest, pushing up prices as new buyers enter the market. Combined with some good, old-fashioned fear of missing out on easy, quick returns (the result of a collection of behavioural biases hardwired into our psychology), this dynamic can lead to prices dramatically disconnecting from the underlying economic value of an asset as more investors crowd into it. However, the 'narrative' is essentially just the consensus opinion constructed from the collective psyche of market participants. When the consensus narrative changes for an asset that has divorced from underlying fundamentals, the outcome to investors is usually a permanent and material loss - particularly when huge amounts of borrowed money have been involved in bidding up the price. The 2007/2008 US housing market crash ("house prices can only go up!") that triggered the Global Financial Crisis is a vivid example of what can happen when crowded assets owned by leveraged speculators undergo a material change in narrative. The AIM investment process is based on determining the intrinsic value of a business. While market value tells you the price other people are willing to pay for an asset, intrinsic value shows you the investment's value based on an analysis of its fundamentals and financials. We believe that discounting future cash flows that can be distributed to the owner of an asset is the best way to determining the intrinsic value of most investments. While there are some shortcomings, it has the advantage of anchoring our estimate of value to some sort of economic reality. Digital assets Of late, there has been an explosion of interest in non-cash-generating assets where determining a reliable estimate of intrinsic value is nearly impossible. We would point to the meteoric rally in cryptocurrencies, or the sudden interest in non-fungible tokens (NFTs) - essentially, tradable digital certificates that use blockchain technology to prove ownership and origin of digital assets - as examples. (Christie's recently auctioned off an NFT of the work of digital artist Beeple for USD69.3mn; the image remains freely viewable and downloadable on the internet.) These assets may have utility and even scarcity over the long term, but recent price action seems to us to exhibit all the hallmarks of a Keynesian Beauty Contest. The behaviour has arguably spilt over to other asset classes and certain pockets of the equity market. Given that capital is essentially free, many market participants are using borrowed money to place leveraged bets on asset prices continuing to rise. We find it noteworthy that there have been several liquidity-driven 'unwinds' in markets this year; from publicly available information, massive amounts of leverage were involved every time. We cannot claim to know how any of this will end, but we do know that leverage combined with highly crowded market positioning rarely ends well when an unexpected external event causes forced selling. When allocating our investors' capital, we try to understand whether the expectations embedded in the market price of the businesses we own bear at least some semblance to reality when applying a reasonable range of estimates. We try to control for fundamental risk by sticking to businesses that have strong balance sheets and generate meaningful amounts of cash. (As the wisdom goes: revenue is vanity, profit is sanity, but cash is king.) In short, we think that by sticking to a defined and repeatable process will serve investors a lot better than trying to claim the first prize in a Keynesian Beauty Contest. Funds operated by this manager: |

30 Apr 2021 - Managers Insights | Vantage Asset Management

|

Chris Gosselin, CEO of Australian Fund Monitors, speaks with Michael Tobin, Founder and Managing Director at Vantage Asset Management. Established in 2004, Vantage Asset Management Pty Limited is an independent investment management company with expertise in private equity, funds management, manager selection and operational management. Vantage Private Equity Growth 4 (VPEG4) is a closed-ended Private Equity fund which started on 30 September 2019 and which is due to close on 30 September 2021. The Fund continues the investment strategy of Vantage's previous two Private Equity Funds, VPEG3 and VPEG2. The Fund invests in Private Equity funds based in Australia, along with Permitted Co-investments, to create a well diversified portfolio of Private Equity investments.

|

30 Apr 2021 - Why this COVID-Hit Sector is Still Attractively Priced

|

Why this COVID-Hit Sector is Still Attractively Priced Steve Johnson, Forager April 2021 I don't know about you, but my COVID prediction record was woeful. Home furnishings boom? Nope. Motorbike retailer has best year ever? Nope. Funeral homes have their worst year ever? Definitely didn't see that coming. Everything is easy to rationalise after the event. But the way different sectors were impacted by COVID surprised me. A lot. One of those is the enterprise software sector. These companies sell software to other companies. Think accounting, customer relationship management and project planning software. Unlike software sold to individuals or small businesses, where the user simply buys the product and starts using it, most enterprise software is heavily integrated into a company's operations and customised for each client.

Forager has owned a few of these businesses over the years, including Hansen (HSN) and GBST. There are a handful in the current portfolio too, such as RPMGlobal (RUL), Fineos (FCL) and Gentrack (GTK). Once ingrained in a customer's operations, they are almost impossible to remove, making for sticky revenues and attractive long-term investments. It wasn't any surprise, then, that they were viewed as something of a safe haven in the early months of the COVID panic. In a world where some companies weren't generating any revenue at all, recurring reliable revenues from large corporates looked relatively attractive. Yet look at the table below. On the ASX at least, many of these companies are today trading well below their pre-COVID prices.

It turns out that this prediction wasn't right either. Apparently, some of the revenue isn't as recurring or reliable as investors had come to believe. Most enterprise software companies earn significant amounts of upfront implementation revenue. That depends on winning new clients. And some of the "recurring" revenue is related to clients requesting changes or introducing new features. With employees working from home and much bigger problems to deal with, most corporates have moved IT system upgrades down their lists of priorities. The impact was widespread. The recovery at utilities and airports software provider Gentrack (GTK) took a big step backwards. Bravura's (BVS) UK wealth management clients have hit pause on new deployments. Sales of Integrated Research's (IRI) performance monitoring solutions have been slow. The problems are real, but the share price reactions look overdone. The timing of a recovery is uncertain. But the deals will return, and investor optimism will likely come back alongside them. Both Forager Funds have had their best ever years of outperformance over the past 12 months. That's been a result of capitalising on widespread over-reactions, and being willing to change our minds as the evidence came to hand. In the enterprise software sector, we're doing both. Funds operated by this manager: Forager International Shares Fund, Forager Australian Shares Fund (ASX: FOR) |

30 Apr 2021 - 5 lessons from a decade of growth stock performance

|

5 Lessons from a decade of growth stock performance Steven Johnson, Forager Funds Management 19th April 2021 I wrote last month that Forager has been selling some wonderful business over the past few months. That has been controversial for some of our clients. Never sell a great business is a lesson many have taken from the past decade of growth stock outperformance. I argue that it's not the right lesson. What has worked is not necessarily what works. Which doesn't mean there are not lessons. If holding great businesses forever is the wrong conclusion, hold for longer than you did seems irrefutably obvious given the value of some of these businesses today. A refresher on business valuation The value of a share is the present value of all the future cash flows that it is going to pay you into perpetuity. We aim to buy those shares at discounts to fair value and sell them when they reach or exceed it, amplifying the returns that are generated by the underlying business. With perfect foresight, the logic of this strategy would be irrefutable. Of course, the future is unknowable and highly variable. In practice, we make the best estimate of what those future cash flows are going to be and put a lot of work into understanding the range and magnitude of the uncertainties. Our estimation is going to be off the mark. The question is which way.

So, with that all as a precursor, here are some of the shortcomings I have gleaned when it comes to erroneously concluding a stock is expensive. 1. Reversion to the mean is a thing. But it doesn't need to be soon Jo Horgan, the founder of Australian makeup giant Mecca Brands, was quoted in the Australian Financial Review last week saying: "With same-store sales (growth), we have an absolute goal as a business that we'll never get below 10 per cent" . I admire Jo's optimism. And I'd love to own a share in her business (she says there are no plans to list on the stock exchange). In the long term, however, not only are we all dead but everything reverts to the mean. It's not possible for any business to grow faster than the global economy forever, otherwise, a slice of the pie becomes bigger than the pie itself. But forever can be a long time away. A common valuation mistake is to assume a good business stops growing rapidly far too soon. My valuation models often assume high growth for the immediately visible future, but a reversion to more subdued growth within the next five to ten years. Google and Facebook are recent examples of businesses still growing 20% per annum as they head into their third decades of existence. Australian examples like Cochlear and Resmed have grown at more than 10% per annum for three decades. Sometimes the insight into a stock is not what's going to happen over the next five years. It's what is going to happen in the decades after that, when the power of compounding really kicks in. 2. Great products create their own demand Total addressable market is some jargon you will hear a lot when it comes to growth companies. Rather than making the common mistake of underestimating the growth runway, analysts jump straight to the endpoint. Back in 2010, the Google argument was something like this: Global advertising spend is roughly US$500bn. We expect it to grow 5% per annum over the next 10 years, making for a 2020 addressable market of US$800bn. Online should grow to 30% of the total and I think Google, being the great business it is, can be 30% of the online share. Adding all that up, in 2020 I think Google will be generating US$73bn of revenue. That wouldn't have seemed a stupid guess in 2010. Alphabet's revenue was US$29bn in that year, making it already one of the world's largest advertising businesses. But it was wrong by a factor of more than two (parent company Alphabet's 2020 revenue was a whopping $182bn). Analysts weren't wrong about the shift to online. They just underestimated how much additional demand Google's products would create from customers that previously weren't spending a cent. Millions of small businesses that couldn't afford newspapers or radio now have a way of advertising to potential customers. Google has grown the market and pinched its competitors' revenue.

3. The world is smaller than it's ever been The concept of winner takes all is nothing new. It is simply economies of scale taken to their logical conclusion. Warren Buffett recognised in the 1960s and '70s that most US cities were going to end up with just one newspaper. The newspaper with the most readers generates the most advertising revenue which allows it to spend the most on creating content that attracts the most readers. Supermarkets (size makes for lower prices) and stock exchanges (liquidity) have long shown the same characteristics. The difference in the 2020s is that the winners can be global. Melbourne had one great newspaper business, and so did every meaningful city in the world. Now there's Google, which dominates the Western world. Netflix is not just killing Australia's Nine, it's killing every free to air and cable channel in the world. This is worth keeping in mind when contemplating the value of your business. Harrods and Selfridges were wonderful London-centric businesses. What if Farfetch is the Harrods of the world? 4. Standard heuristics are flawed when valuing rapidly growing companies All of this plays into the most common mistake. "Rocket to the Moon trades at 40x earnings, therefore it is expensive". It's a lazy conclusion (I've been guilty). And it can be very wrong. Twenty years ago someone (me?) looking at Cochlear could have reached that exact conclusion. It was trading on a price to earnings ratio of more than 30. With the benefit of hindsight, you could have paid 150 times earnings and have still generated a 10% annual return (including dividends). All of these heuristics, or rules of thumb, have assumptions behind them that need to be probed. Under what scenario is 40 times earnings expensive? What would it take for 40 times earnings to be cheap? Conventional measures lose relevance in the context of long-term compounding math. When a company compounds earnings exponentially (15% per annum for the last 20 years in the case of Cochlear), the fair value can be a seemingly absurdly high multiple of early-year earnings. 5. Conservatism still the name of the game Having said all of that, I'd still argue the wider trend at the moment is towards dramatic overvaluation of potential growth. The logic used above is being applied to a lot of businesses that don't deserve it. Very few of today's optimistically priced growth stocks will become the next Google or Cochlear. And, because so much of the anticipated value depends on what happens in 10 and 20 years' time, the consequences of overestimating long-term growth rates can be dramatic.

But growth is just another variable. We're going to apply the same margin of safety we apply to all the other variables. And we're not going to let the exposure to any one business become an irresponsibly large part of either Forager portfolio. As Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote in To a Mouse, "In proving foresight may be vain: The best-laid schemes o' mice an' men, gang aft agley." Often go awry they do. Funds operated by this manager: Forager Australian Shares Fund (ASX: FOR), Forager International Shares Fund |