NEWS

28 Jul 2021 - Is Greed feeding the macro environment?

|

Is Greed feeding the macro environment? Jesse Moors, Spatium Capital July 2021 As society was exhaling from the post-war world of 1946, Arthur Lefford from NYU's Department of Psychology took particular interest in people's decision-making ability, especially as many generations (if they were so lucky) had just survived several globally disruptive periods. The new world presented choices and options that could lead to solutions on the social and economic problems that were now presented before them. This evolving case study provided Lefford the platform to challenge whether people expressed the (in)ability to act based on objectivity and rationality. Unsurprising to many of us in 2021, the results of the study found that people's agreeability to a message is often strongly correlated with their perception of the choice being more logical or rational. The inverse also applies; when there is disagreement with a message, people often consider this to be emotional. Decades later as the natural progression of this field of study cascaded into the world of finance, behavioural finance emerged and sought to study the effect of psychological factors on the economic decision-making process. The focus of behavioural finance is the idea that investors are limited in their ability to make rational economic decisions, whether that be influenced by their own biases, by a lack of self-control or resources (i.e. time), by peer pressure (i.e. herd mentality) or a number of other social, cultural and external factors. If studied and watched closely, this irrationality can begin to reveal some patterns of behaviour and can lead to opportunities. The opposing camp to behavioural finance however, is the Efficient Market Hypothesis. The Efficient Market Hypothesis asserts that investors are rational, fully-informed, and that (stock) prices reflect all available information at any given time and therefore always trade at their fair value. Essentially making the ability to generate an excess return impossible. From our perch, it currently appears that the broader financial system may be playing out a behavioural finance tragic's greatest fantasy. Alongside the apparent equity market exuberance and interest in speculative assets, it seems experts and arm-chair journalists are also attempting to forecast when the RBA interest rates will begin to rise. Whilst these pre-emptive calls make for fascinating reading, they can feed into the broader market's fear & greed complex. Simply, when interest rates are rising (or are lifted ahead of schedule), people are fearful they won't be able to pay their (increased) mortgage repayment and when they are declining (or are cut AHEAD of market consensus), greed dominates as money is perceivably cheap(er). From a business perspective, when interest rates rise, it tends to have a detractive effect overall as debt becomes more expensive (increasing the cost of starting new projects, assuming they are partially debt funded), consumer spending rates generally reduce, and cash leaves the system to be channelled elsewhere (e.g. the household mortgage). The converse also remains true, should interest rates be lifted at a point which is BEHIND consensus, this may allow markets to continue climbing further over the near term. Interestingly however, should interest rates rise ahead of schedule and shock the market into price recalibration to reflect this new environment, one would expect fear and by that virtue, volatility to accompany irrationality as it replaces the current market exuberance. Perhaps this is what pundits and experts alike are trying to time or forecast. Timed correctly, one can quickly adjust a portfolio on a value vs growth or technical vs fundamental basis with the intent to be in the more favoured style. We however prefer not to market time or fluctuate between styles to try and match the macro environment. Conviction (or lack thereof) to an investment strategy and ethos can often be the difference between consistent and inconsistent returns. It appears quite likely that at some point in the medium term the RBA will lift interest rates; from the lens of our investment strategy, we believe that timing this movement is largely an exercise in futility. For as long as irrational economic decision-making continues, one can expect volatility and with it, market opportunities for those who look. Funds operated by this manager: Spatium Small Companies Fund |

27 Jul 2021 - AIM FY21 Investor Webinar

| < |

|

In a year largely driven by narrative ("Value! Growth! Reflation! Deflation!"), the AIM GHCF's portfolio of high-quality companies delivered a solid return (+25.8%), with much lower volatility than the market. In this Webinar, the AIM investment team looks at what drove those returns and discusses why we believe ignoring market narratives and focusing on fundamentals is a much better recipe for long-term sustainable returns. Summary: Funds operated by this manager: |

27 Jul 2021 - The Challenges of Short-Term Market Forecasting

|

The Challenges of Short-Term Market Forecasting Ophir Asset Management June 2021 As Australian equities have rebounded from the lows of late March 2020, many investors have doubted the rally's staying power. Pessimists argue that, based on most valuation metrics, stocks are pricey, which implies weak returns ahead. But we believe that this overrates the predictive power of valuations - particularly in the short term. Instead, investors need to understand that long-run equity returns are driven by multiple components, of which valuation is often the least important. Indeed, it is likely that in coming years investors won't be able to rely on rising equity valuations for their returns. To achieve high returns and realise their investment goals in this environment, they are going to have to become even more focused on identifying the companies that can produce strong earnings growth and cash flow. Only 3 components Figure 1 above decomposes Australian equity market returns into their key components. As you can see, there are only three sources of returns:

The first two components of return are generally referred to as the 'fundamental' components, whilst valuations are often referred to as the 'speculative' component of return. The latter has earned this moniker because it is driven by unpredictable investor emotions, such as fear and greed, in the short term. (The sum of these components approximates the return on the stockmarket, shown with a black diamond.) An erratic contributor The sources of return never change. But their order of importance does. That is, during any of the five-year periods presented, one of these variables will exert a disproportionate influence on total equity returns. Conversely, there will be periods where a component makes little contribution. There is no doubt that when valuations expand it can have a dramatic positive impact on total return. But valuation's contribution is highly erratic: sometimes positive, sometimes negative. When the P/E ratio expands, the stock market generally produces double-digit returns. And when the ratio contracts, returns fall into the single digits. In the second half of the 1980s and the second half of the 1990s, for example, the P/E ratio was a strong driver of the era's spectacular market returns. But P/E detracted from market performance through the years 2000 to 2015 when valuations subsided from the start of the high tech bubble. The exhaustion of PE expansion When P/E multiples are expanding, interest rates are typically falling, and vice versa. For the two decades between 1980 and 2000, the downward trend in interest rates boosted P/Es, which resulted in huge growth in total equity returns. More recently, we have seen this play out as central banks worldwide have drastically cut interest rates to support economies facing pandemic pressures. But with interest rates now having already been reduced to the floor, the era of P/E expansion has been exhausted: it is unlikely that rates can fall much low and push further P/E expansion. Instead, rising rates over the coming years -as economic growth recovers -- are likely to force a modest decline in equity valuation multiples, similar to what markets digested through the years 2000 to 2010. This negative outlook for P/E ratios emphasises the other two sources of equity return: earnings and dividends. As you saw in Figure 1, earnings and dividends, unlike the highly volatile P/E ratio, have had a consistently positive effect on total return over the last forty years. In fact, for much of the last twenty years, earnings and dividends have continued to boost total return, while P/Es have hindered market performance. The emerging primacy of earnings and dividends But while earnings and dividends become more important as sources of returns, the period of double-digit earnings gains for the broader equity market will soon be behind us as economies normalise post the COVID-19 pandemic. Going forward, earnings growth will likely occur at a more modest single-digit rate. Fortunately, our investment process has always focussed on finding the companies that can materially grow earnings. In this environment, our expertise in identifying the profitable growing businesses of the future comes to the fore. Meanwhile, because they are often a preferred method of free cash flow deployment, dividends are set to emerge as a more important component of total equity returns. Although we are biased to companies that can grow earnings faster than the market, we will continue to learn everything we can about a company's free cash flow and what it signals for the businesses capital management policies. A solid year of returns from equities Valuations are not good predictors of short-term market returns. It is futile for investors to use valuations to time the market day-to-day or month-to-month. Valuations could fall but that does not mean returns have to be negative if the other two drivers contribute enough. For long-term investors, the best course is to continue investing according to your plan, regardless of what the market does. You may, at times, buy when valuations are high; on other occasions, you will buy when valuations are low. It should all come out in the wash over the long term. Our base case is we expect a year of solid returns from equities in 2021, but with the usually very high degree of uncertainty. At a very high level, the global economic recovery, which is currently playing out, suggests that earnings growth should positively contribute to markets in 2021. The big differences could arise from valuations. Dividends should also be well supported this year, particularly in commodity and consumer-related stocks. We think investors can no longer rely on a rising tide of higher valuations to lift all stocks. Alpha or outperformance, where it can be found, we be a larger portion of total investor returns. For us, we will continue to focus on finding undervalued small and mid-cap companies that through a superior product or service can one day become the future leaders of tomorrow. These type of businesses will continue to be rewarded with expanding valuations as the market recognises their superior growth trajectories. Funds operated by this manager: Ophir Global Opportunities Fund, Ophir High Conviction Fund (ASX: OPH), Ophir Opportunities Fund |

26 Jul 2021 - Why no inflation pass-through is a bigger concern for China

|

Why no inflation pass-through is a bigger concern for China Ben Wang, Ph.D CFA FRM, Jamieson Coote Bonds June 2021 Producers in both China and the US are facing higher costs, prompting growing concerns that inflation could threaten the global economy - but China isn't waiting to find out given its recent history with inflation. Interestingly, Chinese consumers are facing much less pricing pressure than their American peers, so why are the Chinese more concerned over higher commodity prices? This could be a potential headwind to Chinese economic growth. Top Chinese officials like Premier Li Keqiang and Vice Premier Liu He recently expressed concerns for manufacturers and the adverse effect of rising commodity prices including the potential pass-through to consumers for some goods. In response, Chinese regulators were tasked with curbing the excessive speculation in the commodity market by imposing new limits on the trading of commodities and increasing some export taxes. China has clear reasons to fear inflation with memory of past price increases still vivid, including the +135.2% surge of pork prices and +5.2% consumption inflation in February 2020. But, in our view, the threat of no inflation pass-through is more pressing. Is China exporting higher prices? Since joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001, China has engineered a complete industrial system. The upstream raw materials sectors have been dominated by big companies, which are closely associated with central or local governments. These companies have the pricing power to transfer the input cost pressure to mid- and downstream companies. Notably, the producer goods price increased by +12.0% in the last twelve months, as of May 2021. But the inflation pass-through stopped here and did not flow downstream. The price of consumer goods increased by only +0.5% during the same period. Mid- and downstream companies failed to pass the higher input cost to the consumers. A few factors contributed to the no pass-through of inflation which are discussed below. Figure 1 - China Producer Goods vs Consumer Goods Firstly, the competition at the mid- and downstream level is fierce. When Chinese manufacturers had a limited technology edge, they won market share via lower prices thanks to cheap labor costs. This led to overcapacity and triggered the supply side structural reforms of 2015. Prior to the full blown COVID-19 impacts, industrial upgrading and technology innovation was still undergoing and far from complete. In short, if your competitive edge is price, you cannot jack-up price so easily. Secondly, there is no positive domestic demand shock in China. Unlike many developed countries, the Chinese government didn't implement a large fiscal transfer to boost household balance sheets. The recent retail sales and service output data showed that demand is growing but at a lower-than pre-COVID-19 speed. With largely stable domestic demand, mid- and downstream manufacturers could not raise prices without losing market share. Due to the strong recovery of overseas demand, those downstream manufacturers, who have the capability to compete in overseas markets, may charge higher prices, i.e. exporting the inflation. However, the recent appreciation of RMB has posed a headwind. The latest survey data shows the slowdown of new export orders. Figure 2 - Chinese producers pass through the price pressure to US customers

Overall, high commodity prices without inflation pass-through simply means profit squeezing for mid- and downstream firms. In late May 2021, Chinese state media reported that some downstream producers stopped taking new orders as the more they produced the more they lost. In our view, China shouldn't worry too much about the threat of the high consumer inflation for now as it is difficult for downstream producers to pass through the price pressure. However, the profit squeezing caused by the no pass-through is right here. We believe it is a headwind to Chinese economic growth, which explains why policy makers are tackling the high commodity prices. Some Chinese trading firms have increased inventory of physical commodities and tried to corner the market. Regulators called them to stop the market speculation and manipulation. China would also maintain the macro prudent policy and keep the credit impulse low. This would avoid spurring the property bubble further. Historically, lower China credit impulse was linked to lower commodity prices. However, things may be different this time. The expansionary fiscal policy from the Biden Administration could make the U.S., instead of China, the marginal buyer in the commodity market. While U.S. consumers use the stimulus money to pay for higher gasoline prices during their summer trips, Chinese producers could face further profit squeezing. History suggests that the turning of profitability in the Chinese corporate sector can have significant impacts on regional equity markets, with associated impacts across the macro spectrum, investors should pay attention to the lack of pass-through pricing power given this higher inflation impulse in China as an early warning sign of fading corporate profitability. Figure 3 - China Credit Impulse falling Figure 4 - China Corporate Profit Index vs MSCI Asia x Japan Index Funds operated by this manager: CC Jamieson Coote Bonds Active Bond Fund (Class A), CC Jamieson Coote Bonds Dynamic Alpha Fund, CC Jamieson Coote Bonds Global Bond Fund (Class A - Hedged), CC Jamieson Coote Bonds Global Bond Fund (Class B - Unhedged) |

23 Jul 2021 - Global megatrend observations: The biggest market events over the last 90 years

|

Global megatrend observations The biggest market events over the last 90 yearsInsync Funds Management 10 July 2021 Last year, we endured some major shifts in the market. Just 23 trading days resulted in the S&P 500 falling -34%. By June it had topped +40% (from its 23 March low). It can be disturbing when this happens in such a short timeframe, especially with the media going ballistic with doom and sensationalism. Is this usual? Yes, it is. Large ups-and-downs occur all the time - though not for the past 10 years. So it feels unusual and can be tempting to time moves or cash out until things feel okay again. Here are the seven biggest market events over the last 90 years:

Three demographic discoveries that affect investments To understand the drivers of the structural down-shift, we need to first look at the reality of the globe's demographic make-up. Our white paper discusses three demographic discoveries - and at least one of them will challenge long-held beliefs! Discovery 1: The world population will grow for the next 30 years and there's not much that can be done to stop this. Discovery 2: World population will then decline and there is little that can be done to stop this if societies behave as they have done for millennia. Discovery 3: 'Peak Child' occured in 2011. There will never be a year in our lifetimes where more children are born. This has profound economic growth implications. Learn more in our demographics White Paper: The GDP Downshift - Preserving Equity Returns Disclaimer Funds operated by this manager: Insync Global Capital Aware Fund, Insync Global Quality Equity Fund |

23 Jul 2021 - Beating inflation with private debt: who's in your starting eleven?

|

Beating inflation with private debt: who's in your starting eleven? Simon Petris Ph.D., Revolution Asset Management June 2021 Recently, there's been a lot of discussion about whether the significant government stimulus, combined with record low interest rates and unconventional monetary policy such as Quantitative Easing (QE) will finally result in rising inflation, something markets have not experienced for some time. After a number of false starts, it appears that almost every central bank is committed to these measures until they achieve their objective of realised inflation. It's a risk of which investors should be aware. On a practical level, it means taking a look to see whether the assets in your portfolio are still match-fit in an environment of rising inflation. We have previously written on the critical role of the attacking defender as it relates to private debt illustrated through soccer, so we'll extend this soccer team analogy to explore this dynamic and the role private debt can play to help investors navigate an environment of rising inflation. Moving market dynamics Long-duration assets like government bonds, infrastructure, property, and high-growth equities benefit when interest rates fall by lowering the discount rate applied to all their future cashflows. These are the first assets selected in your team when rates are falling. We have seen these champion investments perform exceptionally well over the bull market of the last 40-years, when interest rates have dropped from double digits to near-zero levels. With the potential for rates to rise from zero and with the prospect of inflation, it's time for the coach and team manager - in markets, the portfolio manager - to make some difficult decisions about whether champion players in the twilight years of their career - for example sovereign bonds - should still be on the field, at least for the whole match. It may be time to re-evaluate whether your best past players are really your top choices going into a new season, or whether they should be retired, rested, or spend less time on the pitch because they've lost a yard of pace. When inflation expectations rise, interest rates tend to increase, and the yield curve steepens. In these conditions, it's an opportunity to reconsider whether some of the long duration assets that have been tried and tested players in the portfolio are still fit for purpose. It might be time for short duration asset classes such as private debt to step into their role in the team. In a rising interest rate environment, the value of long-duration assets like fixed rate corporate and sovereign bonds, fall in value because their future cashflows are discounted further than before. This isn't the case with private debt, which is short duration and senior secured debt, and in a rising interest rate environment does not fall in value, giving true diversification benefit. Australian & New Zealand Private Debt: Appeal in a rising rate environment The chart below illustrates various credit and fixed income investments with differing levels of duration. The longer the duration, the more sensitive the investment valuation will be to interest rate changes.

Like any soccer team, sometimes the coach or manager needs to bench certain assets because they don't suit the playing conditions. But when conditions turn, it could be time to bring them back into the team. Gold is a good example, which has historically served as a store of value when inflation rises. Perhaps it's also time to have an eye to the future and consider whether to promote up-and-coming players from the youth team. In this example, the coach or portfolio manager might examine whether an allocation to crypto currencies may add diversification to your portfolio in a QE world, but we'll leave it to others to continue this debate. Re-positioning for the times Overall, what's important is to have the right balance of attacking and defensive assets in a portfolio for the current conditions. You pick a different team when the game is played in rain and snow compared to when the conditions are fine. When it comes to investing, what's important is to choose the right assets for the prevailing economic and market environment. Think of private debt as the attacking defender or wingback in the team, it provides the right balance in a portfolio because it produces uncorrelated returns to other assets, as we demonstrated in our previous article. It's an investment that's first and foremost a defender that aims to preserve capital, but at the same time, it can contribute to the attack and goals in the form of regular income that can either be spent or used to re-balance. Just as with soccer players, consistency is the key to selecting a fund manager that has the form for managing a portfolio through different conditions. At the same time, a good fund manager - and good players - will be well-balanced, durable and without weaknesses. Private debt as an asset class is an especially attractive option, particularly when inflation is rising, something with which markets have not had to grapple for some time. Revolution Asset Management's goal is to be the attacking defender in investor portfolios by providing that winning and balanced combination of attack in the form of potential income, and defence in the form of aiming to provide capital preservation through all market cycles. This article is for institutional and professional investors only and has been prepared by Revolution Asset Management Pty Ltd ACN 623 140 607 AFSL 507353 ('Revolution') who is the appointed investment manager of the Revolution Private Debt Fund I, the Revolution Private Debt Fund II and the Revolution Wholesale Private Debt Fund II (together 'the Funds'). Channel Investment Management Limited ACN 163 234 240 AFSL 439007 ('CIML') is the Trustee and issuer of units for the Funds. Channel Capital Pty Ltd ACN 162 591 568 AR No. 001274413 ('Channel') provides investment infrastructure services to Revolution and Channel and is the holding company of CIML. None of CIML, Channel or Revolution, their officers, or employees make any representations or warranties, express or implied as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information, including forecast information, contained in this document and nothing contained in this document is or shall be relied upon as a promise or representation, whether as to the past or the future. Past performance is not a reliable indication of future performance. All investments contain risk. This information is given in summary form and does not purport to be complete. To the extent that information in this document is considered advice or a recommendation to investors or potential investors in relation to holding, purchasing or selling units in the Funds please note that it does not take into account your particular investment objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any information you should consider the appropriateness of the information having regard to these matters, any relevant offer document and in particular, you should seek independent financial advice. For further information and before investing, please read the relevant Information Memorandum available on request. Funds operated by this manager: Revolution Private Debt Fund II, Revolution Wholesale Private Debt Fund II - Class B |

22 Jul 2021 - What to learn from the last year's IPO Winners and Losers

|

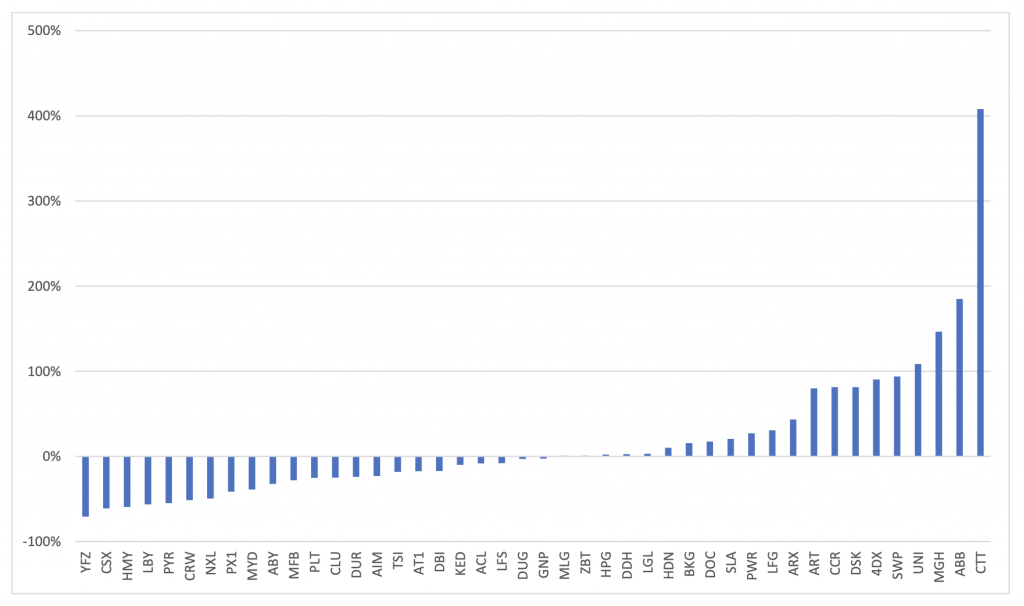

What to learn from the last year's IPO Winners and Losers Gary Rollo, Montgomery Investment Management June 2021 IPOs can give you wonderful returns if you get them right, but burn your money if you don't. And that's clearly shown in the trajectories of the companies that have listed since the COVID-induced market lows in March 2020. Because, while there were some big winners - like Cettire (ASX:CTT), Aussie Broadband (ASX:ABB) and Universal Stores (ASX:UNI), there were also some clear losers. Our process at the Montgomery Small Companies Fund is designed to seek out companies with an under-appreciated or undiscovered competitive advantage with capable management teams that are early in their value creation journey. The IPO market can be a good place to look. So what's been happening in this area of the market since the market's COVID lows and what did we do? The IPO market since COVID The first IPO out of the blocks in the COVID market depths was a $30 million raise for Atomo Diagnostics (ASX:AT1) at 20c a share. AT1 listed with an agreement already in place to provide COVID diagnostic kits to needy European Government type customers. It seems that whatever solace the market is looking for at any given moment in time, there is an IPO for that! Day 1 turned out to be AT1's best day (so far) - trading at over 50c, but it's been downhill ever since, with the stock now trading 20 per cent below issue price at 16c or so today. Quite a journey. There is a message in the AT1 story. The valuation regime of an IPO is an unknown, brokers do a good job to select IPOs that they can "get away" essentially giving the investor crowd what its craving, the flavour of the month. And brokers work hard to whip up demand, this can result in extreme pricing dislocation events. Our job is to be on the right side of that event. Picking those businesses that can go on to create that value for our investors in the Fund. The ones that go up and stay up. There are many IPO events - we go through the stats below - so our process involves an initial screen, to see if the IPO candidate likely has the characteristics that we are looking for in the portfolio, before selecting which ones to spend the time and effort doing proper due diligence on. Doing the work at IPO helps get an understanding of a company that can pay dividends down the track, even if we don't decide to invest on IPO, we try to do the work on as many as we can. The stats: By our count there have been 110 IPOs since the market COVID lows in March 2020. 39 of these have been resource exploration plays, all but 2 have been sub $50 million market cap. Microcap resource exploration plays is not an area of the market the Fund goes hunting in. Too speculative. We don't look at those. There have been 71 non-resource exploration IPOs that have listed since the COVID lows, 44 of these have had a market cap on IPO of greater than $50 million. That's our investible universe. Of these 44 listings, the median return since IPO is -3 per cent. 21 are above IPO price, 23 are under. The data says IPOs are not a one way bet, but the chart below also shows that if you get them right there are good returns available. Distribution of IPO Returns post March 2020: IPO price to date

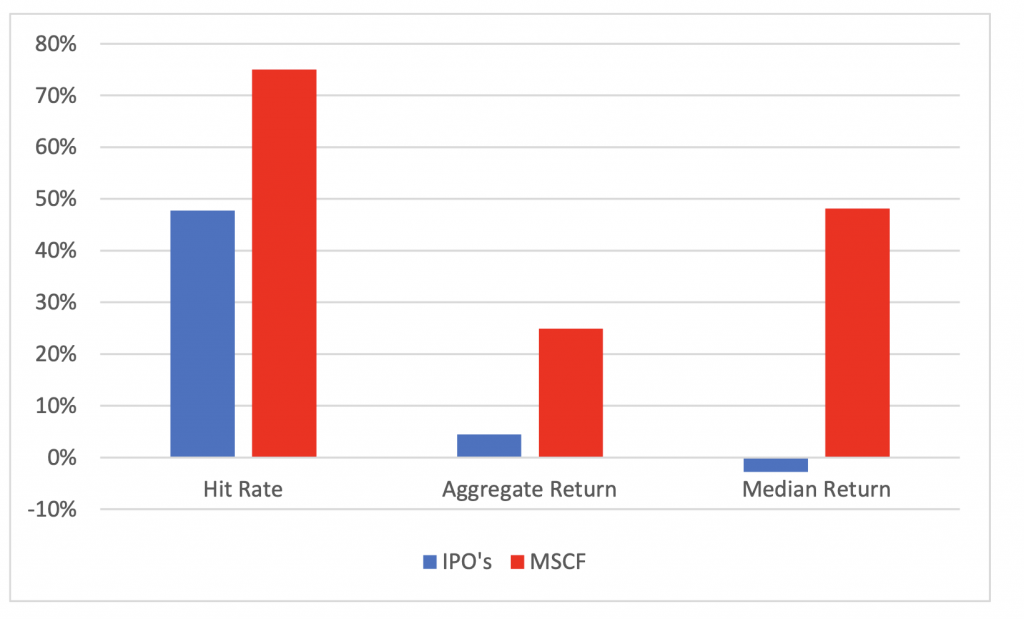

Characteristics of IPO losers One of the most common IPO errors observed in recent times is investors look to play "hot themes" of the moment. Remember if you want it, there is an IPO banking team that has got the deal for you and during COVID times this was meal kits, e-commerce and buy-now-pay-later, amongst other things. An IPO on a "hot theme" can look good in the short run, but can come with longer term pain, as the hot money that chases these "hot" deals does what it does best and moves on to the next shiny thing. Consequently, most if not all of these types of new issues don't find a real investor base anywhere near their IPO price and end up firmly under water. Youfoodz (ASX:YFZ), tried to capitalise on the market's appetite for meal kit delivery that boomed during COVID. Its IPO was "priced" at $1.50, it never traded within cooee of that, best print was $1.32. One way traffic since then. It's 71 per cent down, trading at 44c on my screen as I write, and takes the award for the worst post COVID IPO (to date anyway). My Food Bag (NXZ:MFB), New Zealand's "Youfoodz" provides further illustration of hot theme/hot money loser and is trading 28 per cent below its issue price. Another that looked to cash in on the "moment" was internet retailer Adore Beauty (ASX:ABY). The business was listed on a high valuation, after being acquired by private equity for a much, much lower price only a short time before. At best you could say this was opportunistic. Nevertheless "investors" fluttered like moths around the e-commerce flame when it IPOd at $6.75 in October 2020. That did slightly better than YFZ, however like many moths the "upside" there didn't last long, ABY closed above issue on its first day, but never since and is now down 32 per cent on that IPO price. ABY is arguably now an illiquid micro-cap with a lot to do to re-build its reputation with investors after its warning that it's not growing at the rate investors expected. A downgrade in expectations before it even delivered its first set of full year financials as a listed company is a sin not easily forgiven by institutional investors. A blog on IPOs wouldn't be complete without reference to Nuix (AX:NXL), but given the AFR has done such a good job of disclosure there (better than the prospectus it appears...), we don't feel the need to explain. Caveat Emptor. We didn't do the work on any of the above. Screened out early. The Winners IPOs can be lucrative too, as just as the price discovery process can be difficult for investors, that's the case for the IPO brokers and advisers too, and the business can be sold too cheaply at IPO. IPOs that have performed well include Cettire (ASX:CTT), Aussie Broadband (ASX:ABB), Maas Group (ASX:MGH) and Universal Stores (ASX:UNI). We didn't look at CTT (we thought the e-commerce model was just a child of the times and would quickly slow, time will tell) or ABB (sometimes we miss things). We looked at MGH but thought it was expensive, it's up 150 per cent so I suppose you'd classify that as getting it wrong! We invested in UNI. Of the bottom 10 IPO stocks, 9 of those were "hot theme" stocks, only Harmoney probably doesn't manage to fit that description, although arguably it may have been pitched as such. On the flip side of the top 10 performing IPOs only 2 of them could be considered to be "hot themes" and 1 is a bio-tech (tough to value), the rest have proven business models, some with competitive advantage, many are well run by talented management teams. That's what you need to look for. Montgomery Small Companies Fund IPO report card Of the 44 non-resource exploration IPOs since COVID with a market cap of greater than $50 million, we have looked at 23 of them, the rest we screened out, for one reason or another. We also looked at one sub that market cap level as we thought it could be interesting - a total of 24 active IPO investment decisions were made. We decided to invest in 8, of the 24 we reviewed. Of the 8 we invested in, we made money in 6 of them, sometimes with very good returns. As an aggregate across those 8 we have made 25 per cent return on total capital deployed, with the median return being 48 per cent. It's worth pointing out that only a small fraction of the Fund at any one time is committed to IPOs, for instance of the 8 IPOs we invested in, 5 have been sold, and we hold 3 which are collectively circa 2 per cent of the portfolio. Risk management is always important, especially with IPOs. Early stage companies have higher risk, so we size these in the portfolio so that if they go right we make good returns (see chart below), but if they don't work you won't see us telling you we have underperformed because an IPO didn't go the way we planned. We acknowledge the work done by the advisors and brokers who partner with us, in bringing these companies to market, for the good ones that is, you can keep the bad ones! What about our losers? Of the two IPOs we invested in that didn't work, we made minor losses on one, the other is Cashrewards (ASX:CRW), which hasn't worked (so far) but we continue to hold. We certainly don't get them all right. Montgomery Small Companies Fund IPO report card: 75 per cent hit rate

Of the other 16 decisions where we looked but decided not to invest, 10 of those are under water, 6 made money, although 3 only just. We did miss 3 good opportunities that we did the due diligence on but for various reasons we didn't get over the line. Next time. And we think that there will be a next time for quite some time. IPO banking teams at the banks and brokers report many IPOs in their pipeline, all looking for the right time to come to market. Whilst it's clear to us that investor appetite has moderated, particularly for loss making businesses, we see that as some "heat" coming out of the market. That's healthy and we expect a steady flow of IPOs for us to scrutinise over the coming months. Funds operated by this manager: Montgomery (Private) Fund, Montgomery Small Companies Fund, The Montgomery Fund |

21 Jul 2021 - The cannabis theme, currently up in smoke

|

The cannabis theme, currently up in smoke Harry Heaney, Frame Funds Management June 2021 Why we invested The cannabis theme first caught our attention in December, when a United Nations (UN) commission voted to remove cannabis from Schedule IV of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. The decision removed it from being in the company of more dangerous and addictive substances like heroin and cocaine. Many investors around the world looked at this move and saw it as a major step to normalising the substance. Immediately after this announcement, prices of cannabis-related stocks began to climb. While the change had no immediate material effect on the space, it was seen as a symbolic victory and a sign to nations that it was acceptable to reconsider punitive criminalision policies. Days later, the US House of Representatives passed the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act (MORE) which decriminalised cannabis on a federal level. In January 2021, some states in America began renewed efforts to legalise cannabis locally. Lawmakers in New Mexico, New York, and Connecticut all made overtures to either medicinal or recreational legalisation. A strong first day of legal sales in Illinois also spurred the belief the industry was profitable. In February, a group of German researchers published a study demonstrating the benefits of medicinal cannabis on patients with Parkinson's disease. By this time, the continued stream of positive news flow had reached equity markets - from the start of November to the 10th February, AdvisorShares Pure Cannabis ETF had appreciated approximately 183%. We began to initiate investments in the theme during the month of December and continued to build positions in companies such as Creso Pharma (ASX:CPH), ECS Botanics Holdings (ASX:ECS) and Elixinol Wellness (ASX:EXL) throughout January. Towards the end of January, it became clear Joe Biden would enter the White House with a Democratic House and Senate. In theory, this would make it easier to pass legislative priorities which strengthened thematic tailwinds and confirmed our view that immanent short-term volatility would present opportunities. Why we exited We have since exited our investments in the cannabis theme for multiple reasons. After significant runs into March, we saw most businesses in the sector become over valued without any real shift in company fundamentals. We also saw a slowing of progress from a governmental and legislation perspective. When it became apparent further legal developments in the industry would be delayed by Congress, prices began to return to more normalized levels, though still inflated. In February, companies issued their half-yearly reports and financial statements. The general market reaction was negative, as business fundamentals could not justify current trading levels across the board. As companies within the sector saw their share price continue to decline in late February and early March, it became apparent the theme required further developments to be in play once again. We subsequently exited our investments. What we want to see next To begin reaccumulating investments in the cannabis sector, we would like to see several developments. The most important is legalisation, not just in the United States but around the world where there are significant markets for medicinal and recreational cannabis. In the United States, legalisation of cannabis would break the regulatory shackles that has been holding the industry back. It would open access to funding from federally registered banks and allow companies who sell cannabis to trade on national stock exchanges (thereby providing easier access to capital). Further developments in the medicinal space would also be beneficial for the theme. If positive research continues to be published around the globe, we expect to see renewed investor interest. Mergers or acquisitions in the sector would also be positive - this would allow larger companies to gain access to better distribution channels and expand market access. Ultimately the objective is to improve business profits and margins, which will make the companies more attractive investments. Funds operated by this manager: |

Can't make it? Sign up anyway and receive a recording after the webinar.

20 Jul 2021 - Webinar Invitation | Laureola Advisors

|

|

Laureola Review: Q2 2021 Wed, July 28, 2021 5:00 PM AEST Please join us for our quarterly webinar where we will discuss the following: 1. Introduction: Laureola Advisors 2. Q2 2021 performance review 3. Analysis of current portfolio and where we are now 4. Upcoming developments 5. Q&A

ABOUT LAUREOLA ADVISORS Laureola Advisors was founded with the belief that investors deserve access to the unique benefits of Life Settlements, with the advantages of a specialist and focused asset manager. The best feature of the asset class is the genuine non-correlation with stocks, bonds, real estate, or hedge funds. Life Settlement investors will make money when others can't. Like many asset classes, Life Settlements provides experienced and competent boutique managers like Laureola with significant advantages over larger institutional players. In Life Settlements, the boutique manager can identify and close more opportunities in a cost effective manner, can move quickly when necessary, and can instantly adapt when opportunities dry up in one segment but appear in another. Larger investors are restricted not only by their size and natural inertia, but by self-imposed rules and criteria, which are typically designed by committees. The Laureola Advisors team has transacted over $1 billion (US dollars) in face value of life insurance policies. |

20 Jul 2021 - Nike: Pulling Ahead of the Pack

|

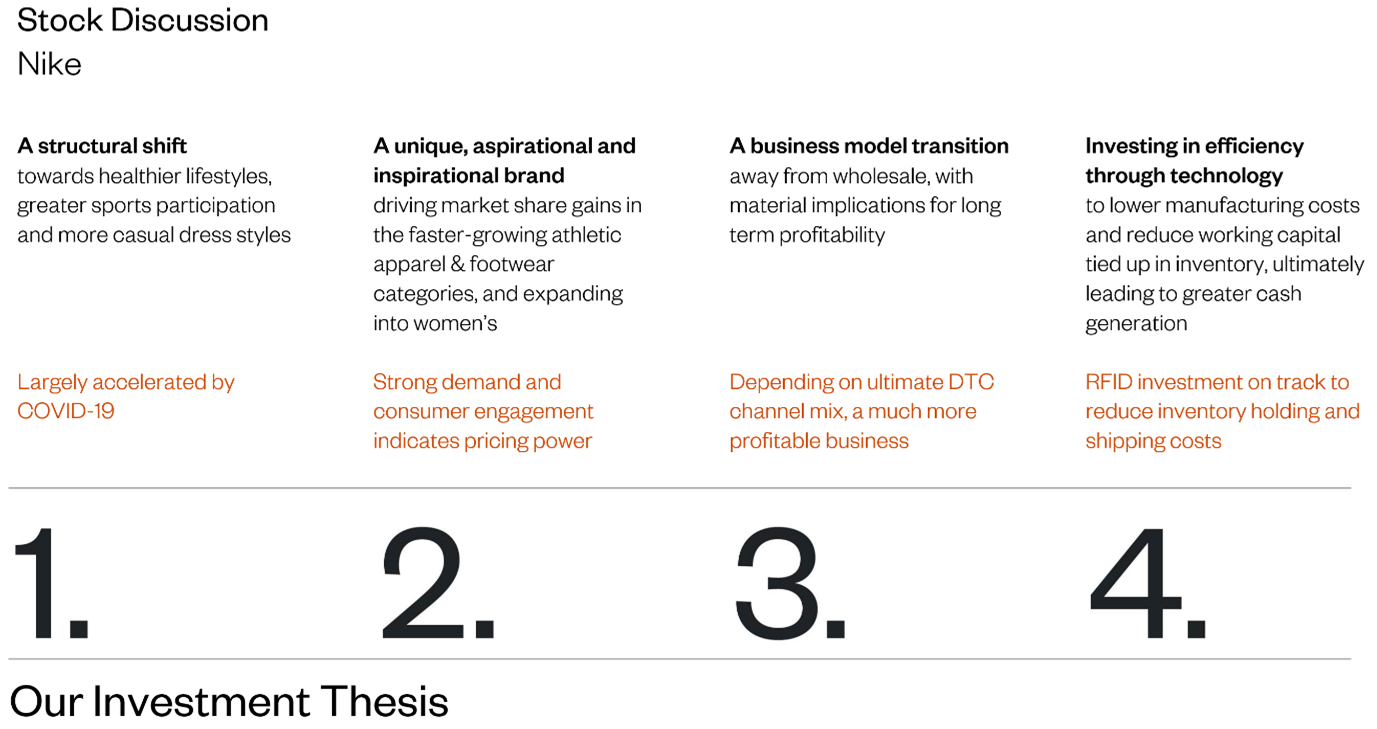

Nike: Pulling Ahead of the Pack Charlie Aitken, AIM June 2021 Approximately nine months ago, we provided a review of our investment case for Nike in 'A Marathon, Not A Sprint'. With the benefit of time, vaccines, additional data points illuminating how consumer behaviour has shifted as a result of the pandemic, and further clarity on Nike's operational performance, it is a good time to take stock and revisit the business again. The slide below is taken from our investor update presented in October 2020, and summarizes the key points underpinning our initial investment thesis for Nike back in August of 2019. While the narrative around Nike for much of the last 18 months has been 'work-from-and-stay-at-home-winner', our view was always that this misses a much more pertinent fact: that the company is undergoing a structural change in its business model that would mean its margin profile would materially increase over the next three to five years. From our October 2020 note:

The valuation impact of this margin uplift is material. In theory, by simply shifting the destination where consumers choose to purchase goods from Nike, the business could end up selling the same number of products at the same retail price but end up dramatically increasing profits. By vertically integrating its distribution to be more in-house, Nike is effectively reclaiming margin back from the wholesale channel. Pulling Ahead of the Pack Last week, Nike reported quarterly results for the period ended 31 May 2021, where management discussed many of the key drivers of performance for the businesses over the next several years. We were happy to hear that an increased focus on Women's shoes and apparel is bearing fruit, as this was a market Nike has historically underserved. (Turns out there's money to be made in specifically catering to the needs of ~50% of the population!) As this trend matures, we expect it to drive faster organic revenue growth for several years, underpinning market share gains. Of further interest was the fact that Nike sees the changing positive attitude towards healthier lifestyles coming out of the pandemic as an opportunity to grow the overall market by promoting sports participation, particularly among younger consumers. The combination of greater insight into consumer preferences is driving not only more targeted product development, but also more targeted (and effective) marketing spend. The interaction of these factors (a structural shift towards healthier lifestyles, expanding into underserved market segments, the shift towards a DTC-business model, and other efficiency gains from investing in technology over the past several years) lead to management issuing the following medium-term (2025) guidance:

Of late, the market has been focused on short-term issues, such as port disruptions in the US (meaning inventory was not able to be timeously distributed to consumers for a period), or a consumer boycott of Nike product in China (which seems to be dissipating already). Historically, such short-term 'glitches' are when long-term investors have the opportunity to purchase great businesses with a margin of safety. (Our initial investment in August 2019 was made at the height of the US/China trade war rhetoric; buying a US brand with a meaningful percentage of sales into China was not exactly the flavour of the month.) By focusing on the longer-term developments that were not yet obvious in the reported numbers - specifically, the change in profitability enabled by the channel mix shift - and understanding the benefits of Nike's 'portfolio' approach to its business (across regions, categories, brands, and sporting codes), the long-term investor would have found much to like. As the margin uplift driven by the DTC shift is now better understood by the market at large, the market valuation has begun to reflect this; in fact, it rallied by nearly 15% on the day following its most recent result as the market capitalised the long-term margin structure into the valuation today. To us, Nike is a case in point where short-term market volatility can benefit the patient investor in buying a quality business at a margin of safety. While we are sure there are still many unforeseen and unexpected challenges Nike will have to navigate out to 2025, the combination of its strong competitive advantages in brand (and, we believe, in execution), strong cash generation, a conservative balance sheet and a high-quality management team steering the ship gives us comfort that the business is a high-quality compounder, and will be for many years to come. Funds operated by this manager: |